A new literary journal, Sun Star, has just released Issue 2 of Volume 1, and one of my translations of Jean Lorrain’s stories, “Useless Virtue”, is in it. And there’s a bonus: the editor has written a short piece in regard to translations of old works in the public domain. If you’d like to read the story, it’s available online for free here. Scroll down to page 29.

I’ve previously written about “Useless Virtue” on my blog, twice, without writing the actual story (which would have disqualified it from being published elsewhere…). I posted here with a translated part of Lorrain’s accompanying introduction to the story, and here with some connections to paintings of Siegfried and the Rhine Maidens that helped me visualise the action while translating it.

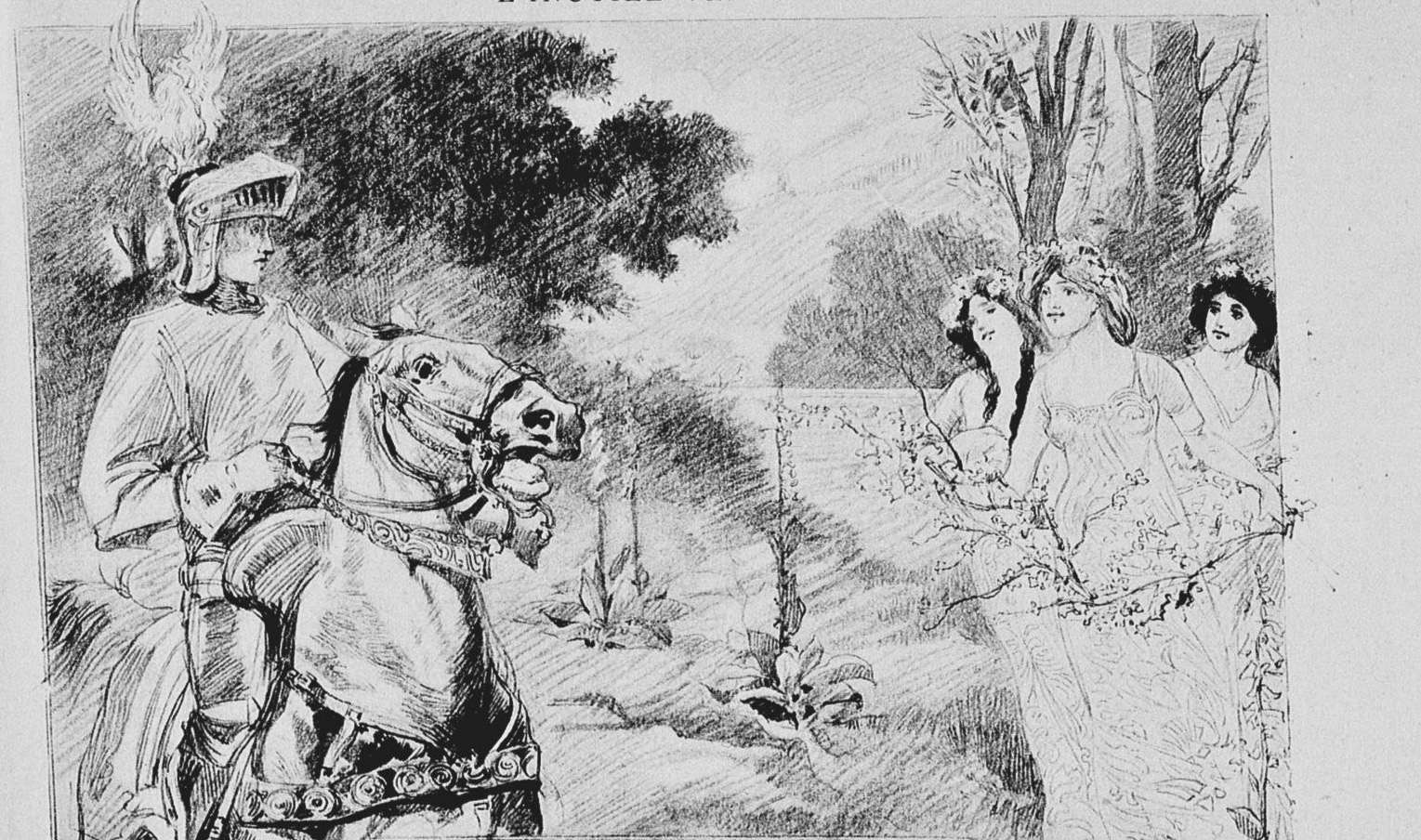

I found the original, “L’Inutile Vertu”, in a small brown book on a dusty shelf at my old university, Contes pour lire à la chandelle (Stories to read by candlelight), but it also appeared later in La Revue Illustrée, a French turn-of-the-century journal which was, unsurprisingly, illustrated, with pages such as this one (courtesy of Gallica).

Illustrated adult books and stories seem to be out of fashion now. But why should children have all the fun of comparing the words to the pictures? For me, it’s an exquisite pleasure to read copies of La Revue Illustrée. True, they’re in French, but there are many examples of English illustrated journals available online that would be a great source of enjoyment for anyone who likes to study drawing styles and the decorated page, not to mention illustrated stories.

If I were gifted with a pencil or a paintbrush, I might have illuminated my own translations. Now there’s a thought. I wonder if there are any translators out there doing just this…

*****