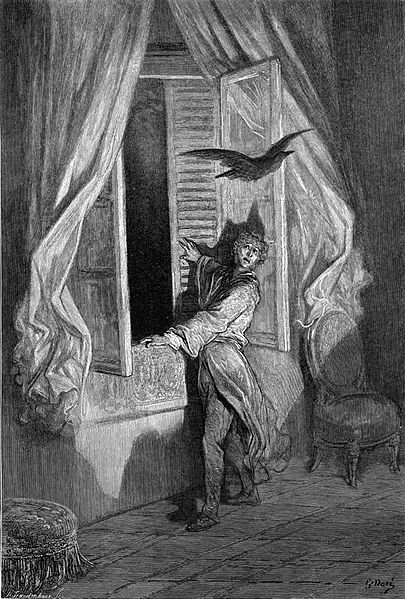

Mother died today.

The Outsider, Albert Camus (trans. by Stuart Gilbert. Originally L’étranger)

*****

Yesterday (no. 14) I posted the first line from The Outsiders. With a final s. Different book, different author, but the same theme of a protagonist who feels like he’s outside of society. Like a misfit.

Today’s post is about The Outsider by Albert Camus. Thousands of words have been penned and keyed about his opening line. In French, it is ‘Aujourd’hui, maman est morte.’ Literally, ‘Today, Mum died.’ Three words that various translators render variously. Today, Mother died. Today, Mummy died. Today, my mother died. My mother died today. Mum died today. Mummy died today. Mama died today. Today, mum is dead. If it’s published in the US, Mum would be Mom.

The maman quandary was mine when I translated the short story Origami by Anne Bihan, in which a small girl refers to her mother as maman, French for Mum and Mummy. Since the girl is Japanese and the setting is Japan, I searched the web and happily found that some Japanese children are starting to use the European-sounding Mama, which I liked for my translation because of its similarity to Maman, and thought it good for retaining a closeness to the French. (I also liked Mama because one of my sons uses it when addressing me…) Of course, I put myself in the shoes of the little girl and remembered that I used to address my own mother as Mummy. But that doesn’t sound Japanese or French; it sounds English. Or Australian. Like me.

What about the actual Japanese word for Mum: Okaasan? There’s not really any question of using it; an English reader with no knowledge of Japanese would be lost. But did I want this child to sound Japanese or French or Australian? Well, Japanese. Ok, so I should write either Okaasan or Mama. Yet, as I wrote Mama Mama Mama, my life’s experience continually prompted me: as a child and then a mother, the word was Mummy (except for one son!). So, at first, I wrote Mummy, then read the story into a recorder and listened to the playback as objectively as possible. It didn’t sound Japanese or French. But does it have to? For me, for this story, it does. I changed it to Mama and read it again into the recorder, played it back and liked it for its Frenchness and modern Japaneseness. Mama it is.

A sidenote: I couldn’t have written this post, repeatedly typing ‘my mother died’, if my very own mother were alive! A second sidenote: On the day Mum died, I was doing some paid work for the French lecturer who had taught me Camus’ L’étranger, and I had to send him an email to say I needed time off for the funeral. I began the email, at first, with Aujourd’hui, maman est morte. Then I deleted it and wrote something less direct, less literary. Perhaps he thought of Camus, anyway.