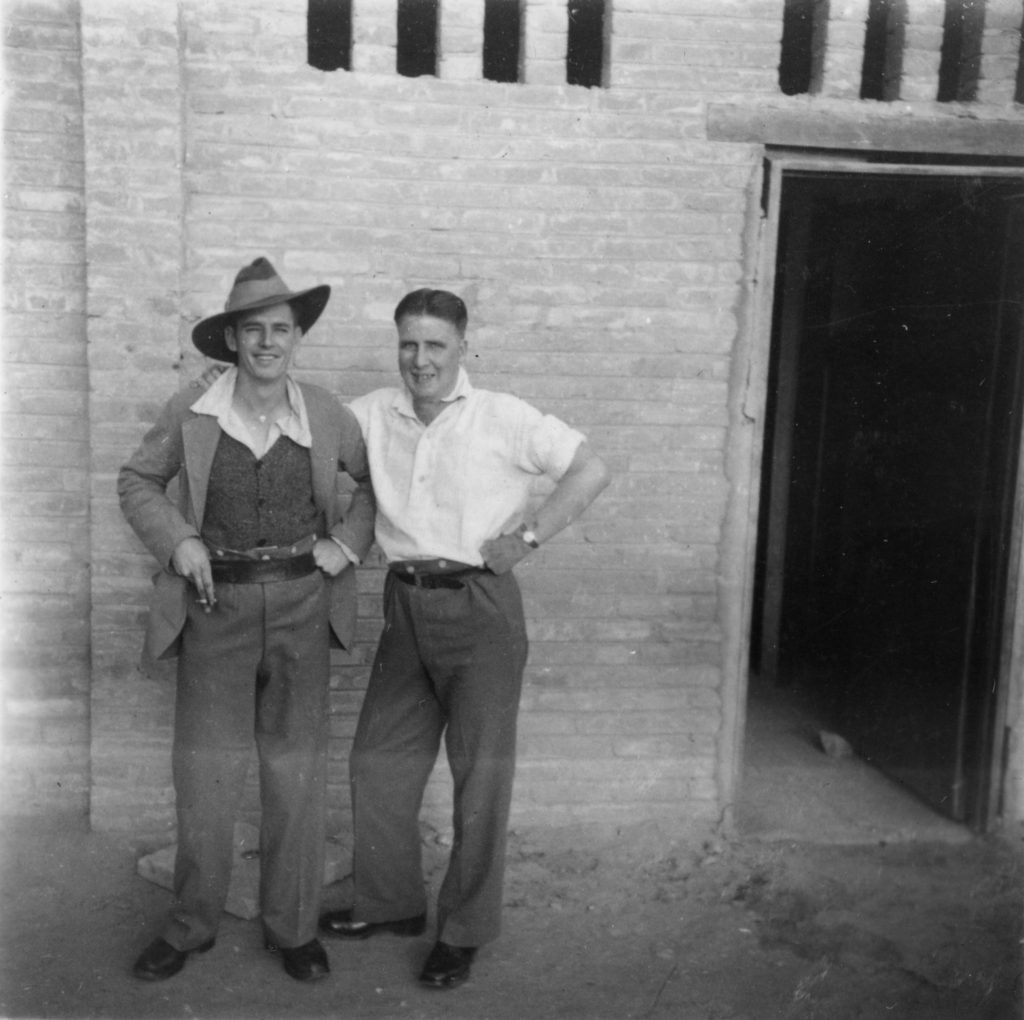

My father died eons ago, but I’ll post one of his poems today, Father’s Day, to thank him for volunteering to join the army to go the Middle East back in the 40s.

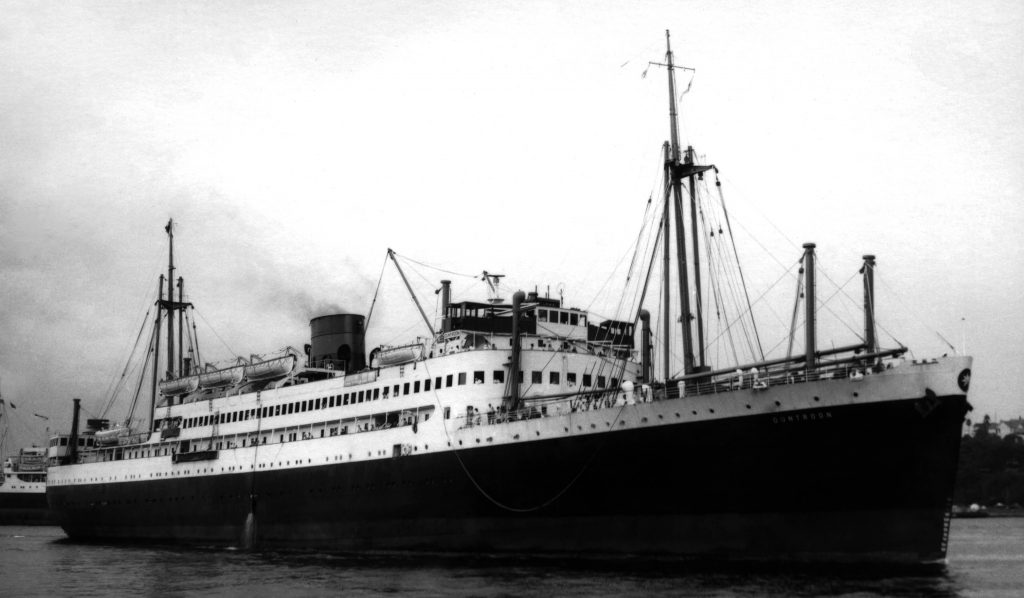

I get the feeling from this poem that as he was thinking and writing, he was probably regretting his decision to go so far from home, but at last he was coming back and couldn’t wait to get off the ship he had sailed on for weeks, the Duntroon. I also get a sense of appreciation for the hard-working nurses who attended him in Kantara Hospital, Egypt, and now on board this ship.

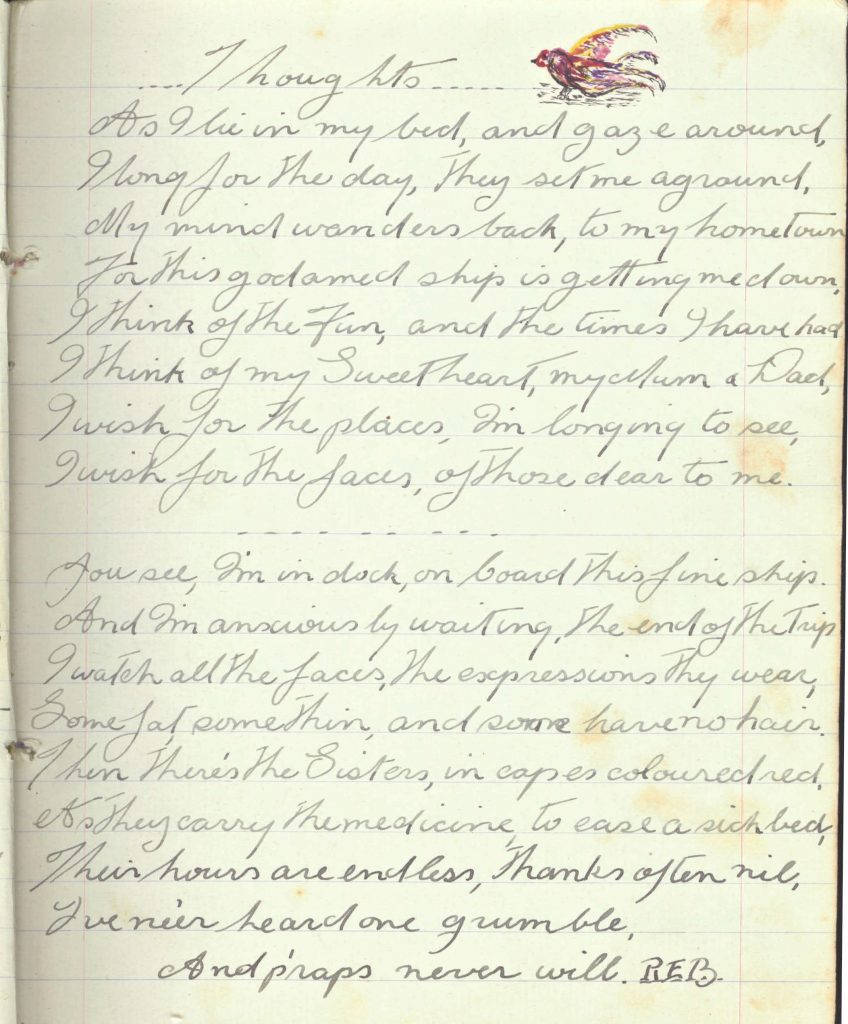

Thoughts

As I lie in my bed and gaze around,

I long for the day they set me aground,

My mind wanders back to my hometown

For this goddamned ship is getting me down.

I think of the fun and the times I’ve had

I think of my Sweetheart, my Mum and Dad,

I wish for the places I’m longing to see,

I wish for the faces of those dear to me.

You see, I’m in dock, on board this fine ship,

And I’m anxiously waiting the end of this trip.

I watch all the faces, the expressions they wear,

Some fat, some thin, and some have no hair.

Then there’s the Sisters in capes coloured red,

As they carry the medicine to ease a sick bed,

Their hours are endless, thanks often nil,

I’ve ne’er heard one grumble

And p’raps never will.

R.E.B.

*