A few days ago in Arthur Conan Doyle’s A Study in Scarlet, I found an account of Sherlock Holmes performing one of his earliest deductions, at exactly the middle of Part I. You can read about it here.

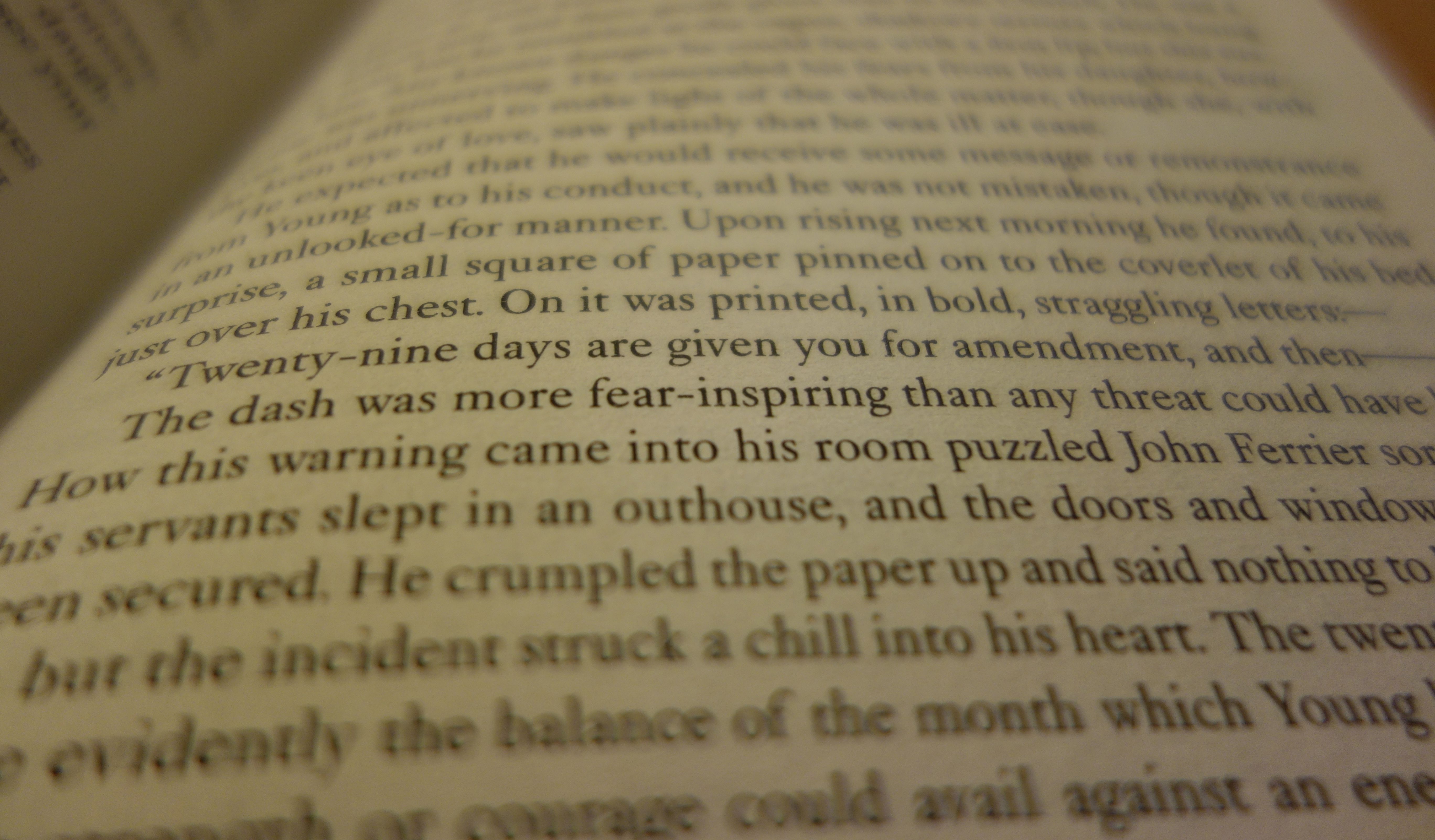

Halfway through Part II of this short novel, Doyle wrote a short paragraph that was not about scientific deduction but rather about an eerie countdown, guaranteed to keep the reader turning pages. The character John Ferrier is given a deadline – 29 days – to hand over his daughter in marriage to one of the Mormon men. The next morning, at the breakfast table, his daughter points upwards:

In the centre of the ceiling was scrawled, with a burned stick apparently, the number 28. . . . That night he sat up with his gun and kept watch and ward. He saw and he heard nothing, and yet in the morning a great 27 had been painted upon the outside of his door.

*****