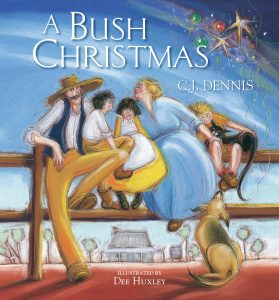

The sun burns hotly thro’ the gums

As down the road old Rogan comes —

The hatter from the lonely hut

Beside the track to Woollybutt.

He likes to spend his Christmas with us here.

Clearly, if you’re reading a poem entitled A Bush Christmas and the first line says ‘The sun burns hotly…’ you can be sure you’re not in northern Europe.

My Christmases have always been hot. Where I grew up in Queensland, the morning temperature in the kitchen would have been, say, 25 degrees celsius, but Mum would never hesitate to turn on the oven and roast the chicken, a luxury. (No turkeys for us.) After a couple of hours of cooking, it would have easily been 35 degrees in that room. I’d keep out of the way and splash around in my small canvas pool while the grown-ups of my family would sit chatting in the shade of the yard. Dad in his long sleeves and trousers, which he wore in all weathers, would be chain smoking on his bench. We’d all wait for Mum to finish roasting the vegetables or making gravy, and then she’d call us to the table. The sweat dripped from her face as she served the food.

“It ain’t a day for working hard,” says the father in A Bush Christmas, and of course, as he speaks, the mother is roasting and boiling and baking in the soaring temperature of the bush kitchen. She’s hot, but guess what the poetic father says…

“Your fault,” says Dad, “you know it is.

Plum puddin’! on a day like this,

And roasted turkeys! Spare me days,

I can’t get over women’s ways.”

Traditions from the old country, the wintry Christmases of England, Scotland and Ireland, are dying hard in Australia, even now. For those from the old country who sought a better life in Canada or the northern parts of the USA, Christmas temperatures were just like home. But those who came to Australia kept up the traditions despite the upside down climate.

A few hours after our Queensland Christmas dinner was over, it was invariably followed by sharp cracking thunder, lightning flashes and a cooling torrential downpour.

But old Rogan of the poem is celebrating Christmas out in the bush, far from any city, where there might not have even been the relief that comes with a storm. Instead, Rogan passes the afternoon telling the kids “his yarns of Christmas tide ‘mid English barns”, “of whitened fields and winter snows, and yuletide logs and mistletoes”.

The children listen, mouths agape,

And see a land with no escape

For biting cold and snow and frost —

A land to all earth’s brightness lost,

A strange and freakish Christmas land to them…

Old Rogan was the lonely neighbour invited for “a bite of tucker and a beer”. They offered him company and a meal, and in return he offered them that valuable form of nourishment for children’s minds, a good yarn.

…The sun slants redly thro’ the gums

As quietly the evening comes,

And Rogan gets his old grey mare,

That matches well his own grey hair,

And rides away into the setting sun…

In the end, the father relaxes with a full belly, and his wife washes up.

“Ah, well,” says Dad. “I got to say

I never spent a lazier day.

This is how it was in my childhood. I’m glad to say some things have changed.

*