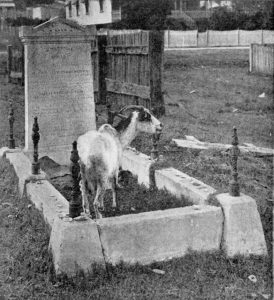

An old cemetery is one of the most pathetic and melancholy spectacles in this world, and the pathos of it is deepened when it has been allowed to drift into neglect and ruin, with broken fences, overturned tombstones, fallen railings, obliterated inscriptions, rank weeds, long grass and general desolation.

Opening line, ‘The Paddington Cemetery’ in Truth (Brisbane newspaper), 17th November 1907

In my last post I lamented the discarding of books by libraries of all ilks. Michael Wilding alerted us to the false promise of libraries to put unborrowed books in storage somewhere. What actually happens to many of them is quite different: they are dumped and used as landfill.

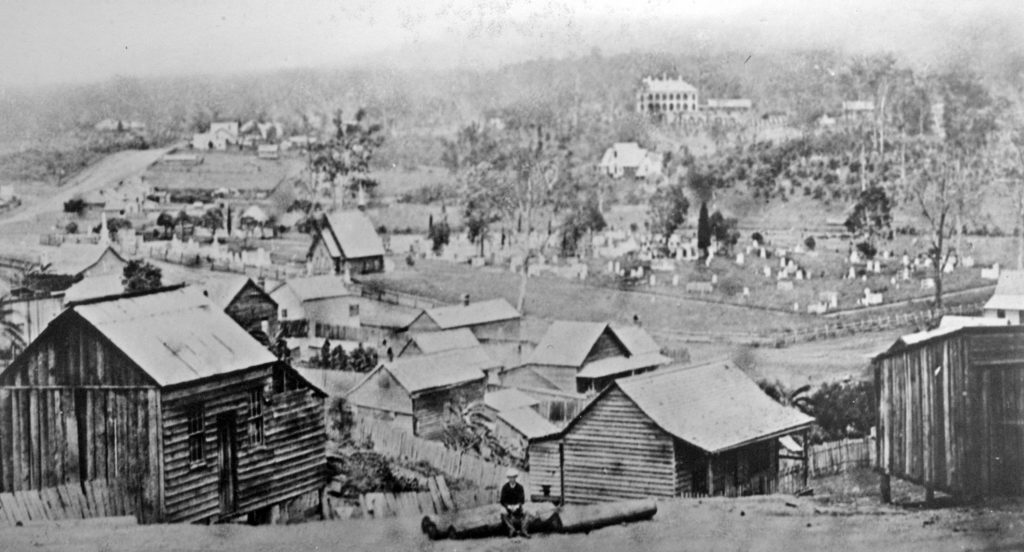

Another element of our civilisation has suffered the same fate. While searching for information about two of my ancestors, siblings Eliza and James Burley who were buried in Paddington Cemetery, I found this article about ‘Bygone Brisbane’ written when the town was all of 80 years old! It’s a sad story from the first. The writer’s adjectives are depressing: broken, overturned, fallen, obliterated … Yet I had to keep reading: why had the graveyard been so neglected? Worse was to come. I discovered that a large number of headstones of Brisbane’s early settlers have been used as … landfill.

Paddington Cemetery opened in 1843 for the first settlers and closed in 1875, and over the following years became an untended, weed-infested, goat-harbouring eyesore. The local population sought a solution from the Council, who proposed a children’s playground, kindergarten and pool to be built over the graves!

But what could they do with the headstones? A Councillor offered a suggestion: “Break them up and use them for the footpaths; they make good road metal!”

The author of the Truth newspaper article where I found today’s great opening line compared the councillor to Troglodytes, “men who have the skulls and intellects of cave dwellers who sat in their dark dwelling places and gnawed the grilled bones of even their own parents, when having a special feast. To such men there is nothing sacred.”

The Burley children lie in the Paddington Cemetery, which itself now lies under a huge football stadium formerly known as Lang Park, these days Suncorp Stadium.

An historian, Darcy Maddock, recently let me know that many of the headstones from the Paddington Cemetery were supposed to have been used for road base (!) but in fact were removed to the newer Toowong Cemetery where they were not re-erected for posterity but rather “placed in a gully” where “someone has used a crowbar to break them up. They were covered over and trees planted over them in the hope no one would ever know.” Darcy and an archaeologist are working with the current Council on extricating the headstones from beneath a large long water pipe laid on top of them.

The gravestones of my ancestors are not, so far, among those lifted from the ditch.

*

Entering the words “headstones landfill” or “books landfill” into Google turns up numerous stories from around the world: burying them in ditches is an old and common practice.

Cemetery administrators make promises to safely remove headstones to new sites, and librarians promise to retain unique copies of books and journals. Yet, sadly, a search too often reveals that the items have “disappeared”.

How briefly we’re allowed to remember people we’ve known and books we’ve read.

*