She was a great-great granddaughter of the King of Poland, Augustus II the Strong. Her father was the king’s great-grandson, Maurice Dupin.

Her mother, Sophie Delaborde, the daughter of a bird fancier, was, said George, of the ‘vagabond race of Bohemians’.

She was a girl with a foot in two worlds, born Amantine-Aurore-Lucile Dupin in 1804 in Paris, raised by her aristocratic grandmother.

She did what women did in the nineteenth century: she married at 18 and produced a child, and a few years later, after some time away from home, she produced another child. Perhaps not by the same father…

She did what women didn’t do: she left her husband to live as a single mother in Paris.

In 1831, she began mixing in artistic circles and changed her name to George Sand.

To be independent, George had to earn her living. She took to writing, lived in attics, cropped her hair, abandoned her expensive layers of women’s drapery and donned cheaper clothing: a redingote, trousers, vest and tie.

Dressing in men’s clothes allowed her to visit clubs and theatre-pits where she closely observed men in their public male spaces and listened in on their literary and cultural conversations.

And dressing in men’s clothes brought her valuable attention as a new author. It helped her books to sell so she and her two children could eat.

In her writing career she considered herself an equal among her male peers, and her works were widely read.

By the end of the nineteenth century, her works were out of fashion.

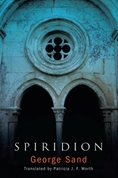

Some of her best writings have been translated into English in recent years. After I read her Gothic novel, Spiridion, (in French), about 3 years and 3 months ago, I had an idea that English-language readers would find it intriguing. When I’d finished reading it, I started translating it. Now SUNY Press is publishing my translation of Spiridion, and will have it ready in May 2015.

George wrote it in 1838/39 while keeping company with Frédéric Chopin, several years her junior. When Frédéric, George and her children sojourned in Majorca for the winter of 1838, she finished Spiridion to the sounds of Chopin composing his Preludes.

But in 1842 George revised the novel’s ending, and it’s this one you’ll read in the English translation.

In Spiridion the audacious George wrote of an exclusively male microcosm where not one female plays a part, a world impossible for her to experience but not impossible to imagine: a monastery where goodness is punished, corruption is encouraged, love is discouraged, and real and unreal demons haunt the cloisters and the crypt.

It was a harsh critique of the rigid dogmas of a monastery and its authorities. “I allowed myself to challenge purely human institutions,” she said, and, for that, some declared her to be “without principles.” Her response: “Should it bother me?”.

Some readers will learn a lesson and find hope in this story. Others will read a mystery based on the evil tendencies of humans confined in an institution, with a positive suggestion or two for living peaceably with our fellow monks.

In May next year, if you’re looking for a Gothic novel with a philosophical turn, keep your eye out for this cover.

George became one of the rare women of the nineteenth century able to earn enough to be financially independent. She was still writing when she died at 71.

*****