This is it, 46 of 46. More importantly, together with the 54 Great Opening Lines I posted a couple of years ago (click on ‘categories’ to go there), now there are a hundred all together.

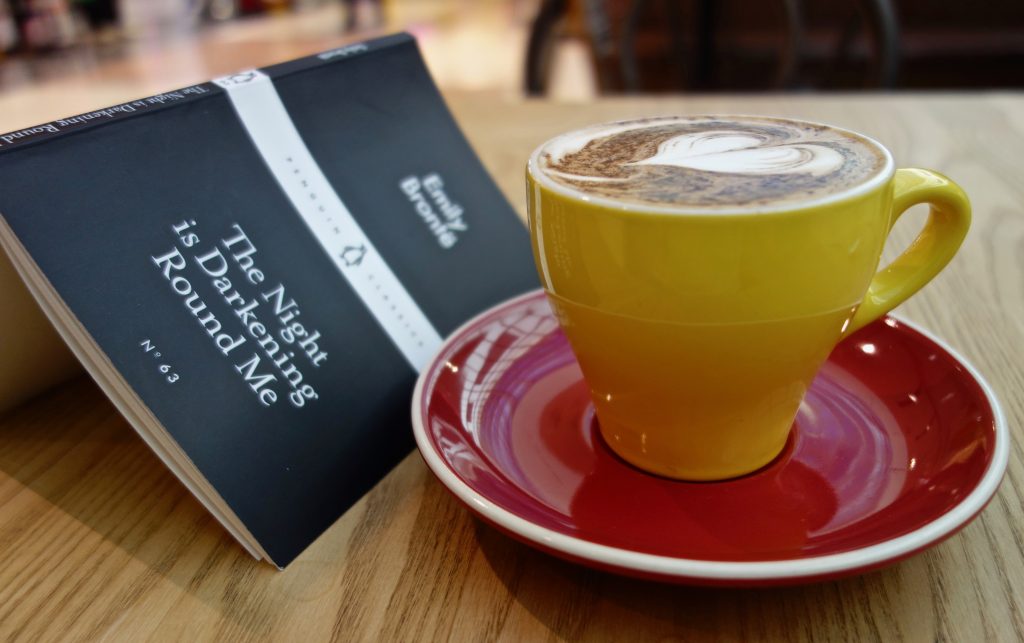

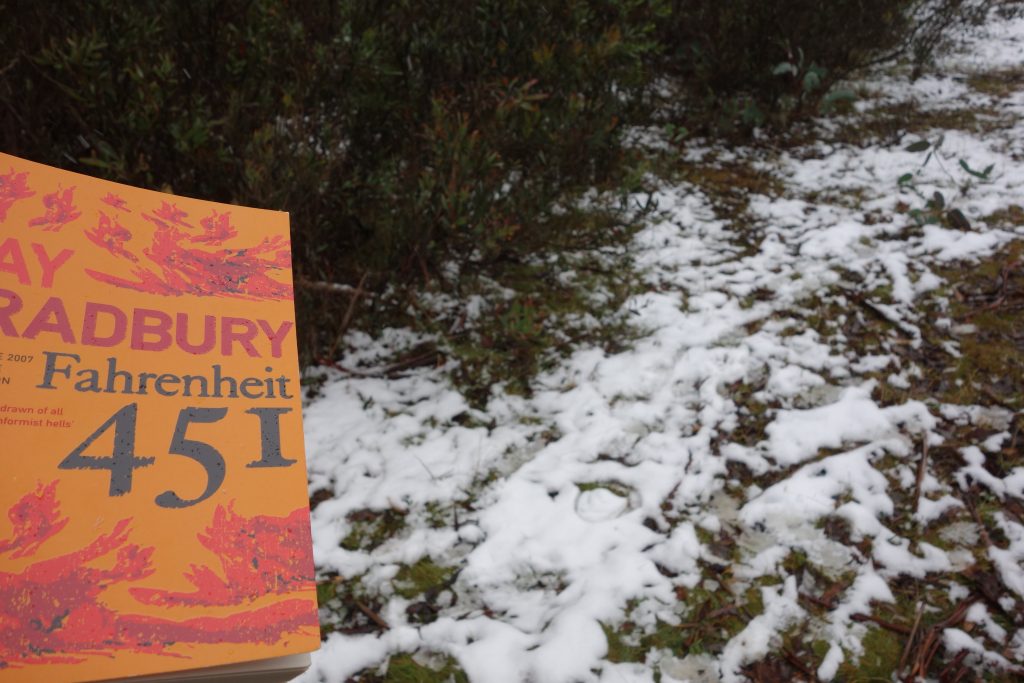

This last opener is from my (unpublished) translation of a book of short stories. Here today in Canberra it’s mid-winter, about 10 degrees celsius with an icy breeze that spoils a good walk. Winter Tales came to mind not only because of the weather but because, as a translator, I’ve been reading it so closely for so long that I want to show you a little of its magic.

It was Christmas, a few years ago. I had been invited to join a wolf hunt in a province of the Russian interior. The morning was superb: ten degrees of frost, a bright sun in a blue sky, not a breath of wind; plains stretching to the horizon, everything a raw white with pink glints and hints of gold; a dead world gleaming like old bone china.

First lines, Winter Tales, Eugène-Melchior de Vogüé, 1893, my translation

Certain words of the first two sentences had my attention from the start: Christmas, wolf hunt, Russian interior.

Set in Russia and Ukraine, these tales are the writing of a French diplomat who lived there for seven years and married a Russian aristocrat. His unnamed narrator, invited to join the wolf hunt, was staying with a host who had lived through the times of serfdom and its abolition. The host tells stories of former serfs, beginning and ending with his own story as a property and serf owner during this era.

*

And that, my friends, is my last offering to the list of Great Opening Lines. I do hope you’ve been inspired to hunt down some of these books, particularly the less-known novels and collections. If you have, please leave me your kind reflections on them.

*

*

*