In the past few months I’ve had four translated stories accepted by journals. In my last post I lamented the silence of two of those journals, but, good news!, one has announced the story will be published in September. And two more have promised to publish another couple of stories, so I’m hoping that all will go well for those journals.

As a lover of Great Opening Lines, I thought I’d include their first lines here as excerpts from the three forthcoming stories.

First:

Hiding behind the hedge, the wolf was patiently watching the house.

Opening line, ‘The Wolf’, Marcel Aymé, translated by me, forthcoming in ‘Delos Journal’

A story for children and adults about a wolf that wants to be good and kind but deep down he’s still an animal …

Second:

Not long ago and not far away, a sculptor in love with his statue as in the days of Pygmalion the King of Cyprus, reproduced the same miracle and brought her to life, transforming the marble into living flesh through which glorious blood flowed by his will and the force of his overpowering desire.

Opening line, ‘The Lydian’, Théodore de Banville, translated by me, forthcoming in ‘Black Sun Lit’

The Lydian is the mythological Queen Omphale who was given Hercules as her slave for a year (his punishment for a murder). She wore the skin of the lion he had killed, and carried his club. Banville’s story tells of a sculptor who produced a statue of Omphale that came to life. He thought his dreams had come true…

Third:

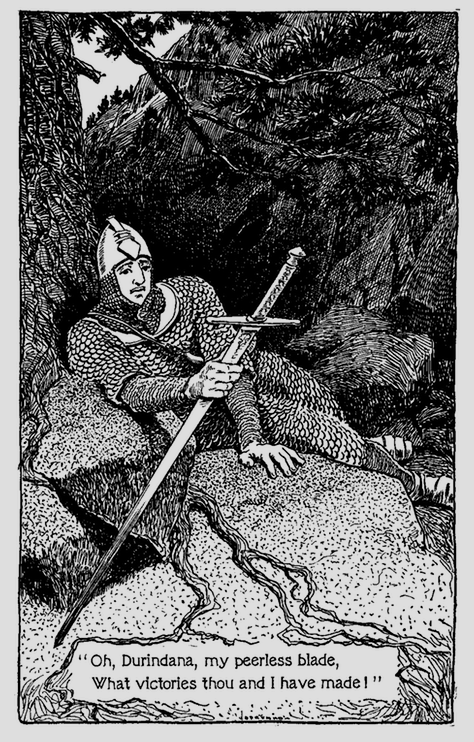

Once when the valiant knight Roland was returning from fighting the Moriscos, he was letting his horse catch its breath in a Pyrenean pass when he heard a shepherd tell of an enchanter, not far from there, who was making himself odious to the whole country by his tyranny and cruelty.

Opening line, ‘Tears on the Sword’, Catulle Mendès, translated by me, forthcoming in ‘The Clarion Call’ anthology

A fantasy about the French medieval hero, Roland, who revels in fights with lances and swords but now must defend his country against a sorcerer who has invented a diabolical weapon that allows cowards to kill from afar.

Keep checking back to this blog to hear news of the stories making it into print.

*

*

*

Thanks Dennis for introducing me to Philip Marlowe. I liked his references to the hot wind through the narration. ‘Outside the wind howled’; ‘… he looked cool as well as under a tension of some sort. I guessed it was the hot wind.’; ‘The wind was making enough noise to make the hard quick rap of .22 ammunition sound like a slammed door…’; ‘The wind was still blowing, oven-hot, swirling dust and torn paper up against the walls.’

Thanks Dennis for introducing me to Philip Marlowe. I liked his references to the hot wind through the narration. ‘Outside the wind howled’; ‘… he looked cool as well as under a tension of some sort. I guessed it was the hot wind.’; ‘The wind was making enough noise to make the hard quick rap of .22 ammunition sound like a slammed door…’; ‘The wind was still blowing, oven-hot, swirling dust and torn paper up against the walls.’