1918. 8 March. There is so much influenza about that they’ve had to shut the university.

Opening line, The Gray Notebook, Josep Pla, 1966, translated by Peter Bush

Catalonia is in the news and on my mind. I’m reading Josep Pla’s The Gray Notebook. And it’s in my face, for my desktop picture is a 1915 painting, L’esmorzar (Breakfast) by Joaquim Sunyer, one of Pla’s favourite Catalan artists.

Sometime last year I found this image online, bright and deep and earthy. But for an unknown reason I can’t find it again, so here’s a photo of my desktop picture. And my desktop. I so enjoy this painting that I haven’t removed it from my screen since I found it. The couple look friendly, as if they’d happily prepare me a meal even if I don’t speak Catalan, or even Spanish. They’re tanned from working outdoors, probably producing the food on their table and the tables of the townspeople. They’re rugged and strong, a little reminiscent of Vincent van Gogh’s Potato Eaters but healthier.

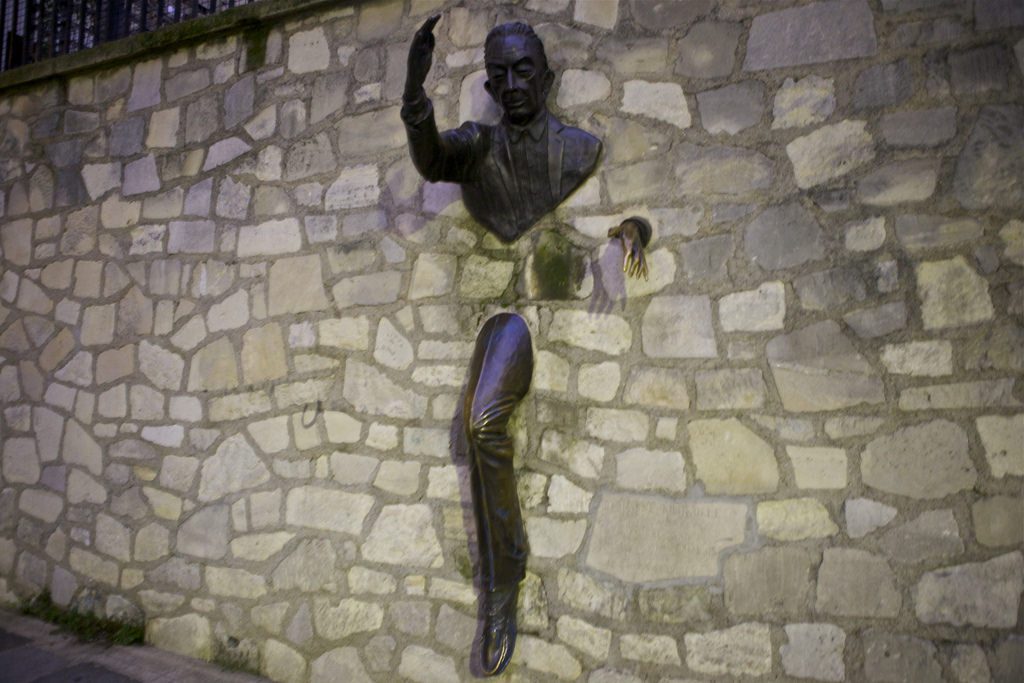

The colours of south-east France and north-east Spain (or Catalonia) are warm and inviting, baked yellow and clay red, like the colours of the Catalan flag, like the colours in this wall plaque I snapped in Port-Vendres, not far north of the French-Spanish border.

This sense of real life, of a colourful realism, is what I’m reading in Josep Pla. The book is a diary written over twenty months, beginning the day Josep turns 21, but it wasn’t published until he was 69, by which time he had transformed it with added stories, reflections and a little stretched truth. It’s filled with descriptions, yarns, recalled childhood images, and plenty of cynicism. More than anything it revives my own pleasant memories of Pla’s part of the world, Catalonia.

*