Aleksey Fyodorovich Karamazov was the third son of a landowner in our district, Fyodor Pavlovich Karamazov, so noted in his time (and even now still recollected among us) for his tragic and fishy death, which occurred just thirteen years ago and which I shall report in its proper context.

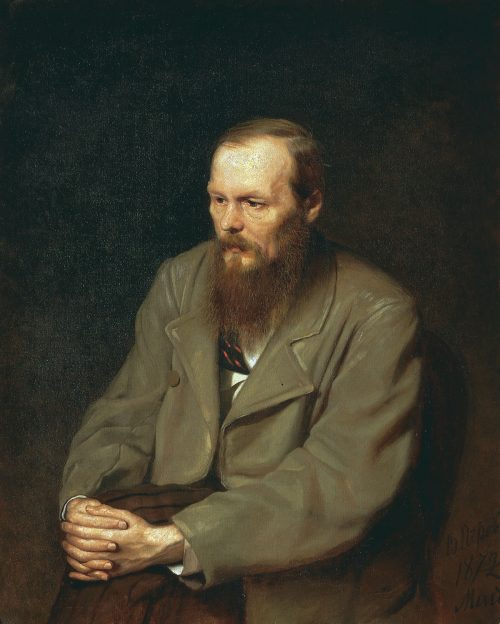

Opening line of The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoyevsky, 1880, translated by David McDuff (1993)

This famous book actually has two beginnings. The first is an epigraph from John 12:24, words which are also engraved on the front of Dostoyevsky’s tomb in St Petersburg.

The second is the opening line of Part One, Book One, as quoted above in a translation by David McDuff. When I first read this translated line, I thought it was Aleksey who’d had a tragic and fishy death. Comparing McDuff’s words with those of Constance Garnett who in 1912 published the earliest English translation of The Brothers Karamazov, I noticed not just the different spellings, Aleksey/Alexey, but I also learned a lesson about ambiguity. The same sentence in Garnett’s translation makes it immediately clear that the father, Fyodor, had died:

Alexey Fyodorovitch Karamazov was the third son of Fyodor Pavlovitch Karamazov, a landowner well known in our district in his own day, and still remembered among us owing to his gloomy and tragic death, which happened thirteen years ago, and which I shall describe in its proper place.

In the McDuff lines, Aleksey is first placed in his family context and the rest of the sentence therefore must be telling us why he was ‘noted in his time … for his tragic and fishy death’. On the other hand, the Garnett lines speak clearly of Fyodor, the father, as ‘a landowner … still remembered among us owing to his gloomy and tragic death’. No confusion.

Little lessons like this one are invaluable for translators. The risk of ambiguity is reduced with each pair of fresh eyes reading the words. Of course, The Brothers Karamazov is 971 pages long, so if the translator couldn’t find many friends to proofread so long a manuscript, we would understand.

*

The different spelling of Aleksey is perhaps unremarkable, considering that the original would have been in cyrillic script. Thus, the translator may be reliant on phonetic pronunciation of the name? [I defer to your translator’s skills for confirmation, Trish]

In any case, who are we to question such variations, when Shakespeare’s and Raleigh’s names have been spelled many ways?

It’s a translator’s dilemma, knowing whether to keep the spelling in the source language or make it more English. If I had a choice I’d choose the x. Much better than a k. 🙂