On the unpredictable path of life I’ve ended up translating French literature from different hemispheres and different centuries. I’ve written about authors from 19th-century France who’ve taken my fancy with their fairy tales and fantasies, and now I want my readers to become acquainted with an author from 21st-century New Caledonia, Claudine Jacques.

My first encounter with Claudine’s writing was at university. I very much enjoyed studying the social problems laid out in her stories and was surprised to find numerous similarities between the histories of Australia and New Caledonia. Her writing is compelling and keeps me turning pages till the last. My favourite is Cœurs barbelés, part fiction, part history, based on the painful experiences of white Caledonians and the indigenous Kanak people trying to live harmoniously on an island.

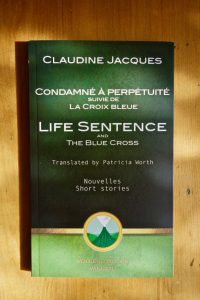

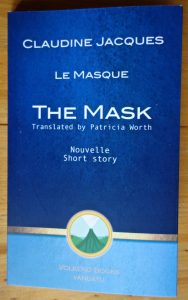

I’ve enjoyed translating a few of her short stories into English and have been fortunate to have them published: ‘Life Sentence’, ‘The Mask’, ‘Guardian of Legends’, and three that are available online for free, ‘The Blue Cross’, ‘Other People’s Land’, and one set in Vanuatu, ‘Bitter Secrets’ .

Born in Belfort, France, Claudine moved to New Caledonia as a sixteen-year-old with her parents and has since made it her own country. Until 1994 she ran a vocational training centre, but once she had discovered the world of books, she established a publishing company and now devotes herself almost exclusively to writing. In 1997 Claudine and other authors founded the Association des Écrivains de la Nouvelle Calédonie (New Caledonian Society of Authors).

The bush and island life have profoundly inspired Claudine’s work. Her home in the bushland of this Pacific island, on a cattle station in Bouraké, has allowed her to become immersed in the heart of the country and to know it as an insider. Claudine’s novels and short stories are concerned with all “Caledonians”: those of the main island, Grande Terre, those of the smaller Loyalty Islands, the Caledonians of European origin, the Kanak, the Wallisians, the Vietnamese and Indonesians who are all part of the New Caledonian population. Her stories reveal a part of the Pacific that is modern and multicultural, a country in transition.

This is rich, sensual writing that moves readers with its power of suggestion. Knowing that Claudine’s stories are based on her island’s history, they will keep you turning pages. I personally found myself searching for light at the end of some dark tunnels. You’ll find it, as I did, at the end.

*