On an exceptionally hot evening early in July a young man came out of the garret in which he lodged in S. Place and walked slowly, as though in hesitation, towards K. bridge.

Opening line, Crime and Punishment, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, translated by Constance Garnett

Last night I could have written:

On an exceptionally hot evening early in January a middle-aged couple came out of the house in which they lodged in H. Street and walked slowly, as though in hesitation, towards C. bridge.

Yesterday evening and this evening are the endings of exceptionally hot days in Canberra. Today, 39 degrees.

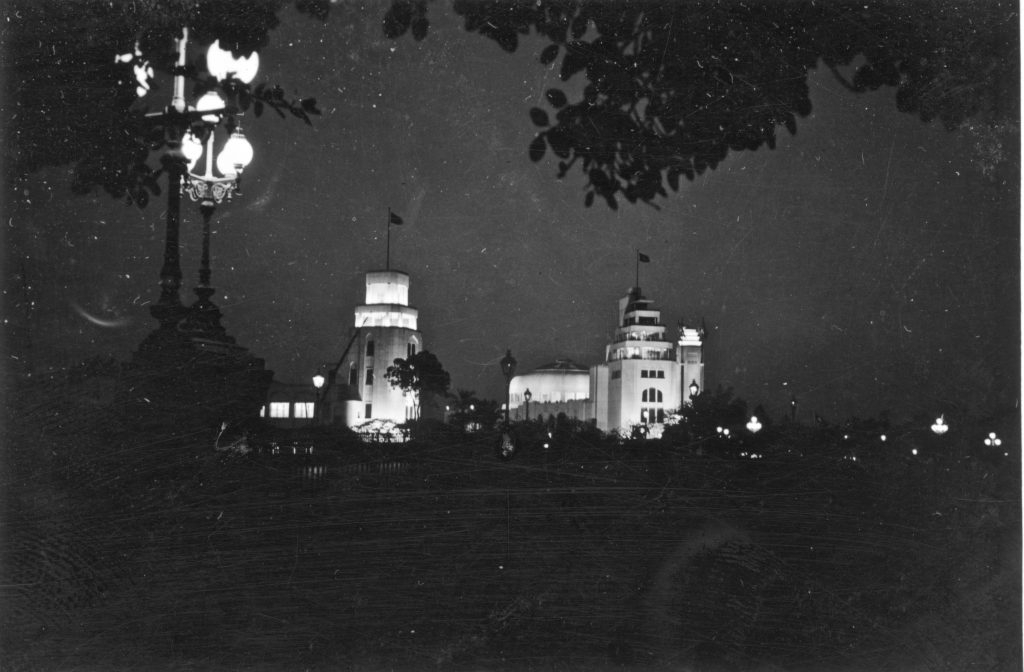

Perhaps you didn’t imagine Dostoyevsky’s character walking towards a bridge like this one. Rather, since I don’t have any photos of Russian bridges, you might have seen him heading for a bridge resembling this old one in Cairo, where the evenings are undoubtedly hot:

I confess I haven’t read Crime and Punishment though I have read other Dostoyevsky works. But when I compared the opening line translated into English by three different translators, I thought it was worth writing about. My favourite is Constance Garnett’s 33 words in a succinct sentence, quoted above. Compare it with the 46 words of Katz’s translation:

In the beginning of July, during an extremely hot spell, toward evening, a young man left his tiny room, which he sublet from some tenants who lived in Stolyarnyi Lane, stepped out onto the street, and slowly, as if indecisively, set off towards the Kokushkin Bridge. (Translated by Michael Katz)

Plenty of detail, but I was lost after ‘sublet’. In my humble opinion there are 13 words too many. That said, I can’t read Russian and therefore can’t really say if there are omissions or additions. Now look at this one by Oliver Ready:

In early July, in exceptional heat, towards evening, a young man left the garret he was renting in S–y Lane, stepped outside, and slowly, as if in two minds, set off towards K–n Bridge. (Translated by Oliver Ready)

The number of words is similar to Garnett’s, but what it loses (for me) is the immediacy in her first words, “On an exceptionally hot evening…”. The other two translators tell us first off what month it is, but that’s not as good a beginning for a great opening line.

Perhaps I’m presently susceptible to Garnett’s first words since it’s about 10 pm and the temperature in my house is still 30 degrees.

*