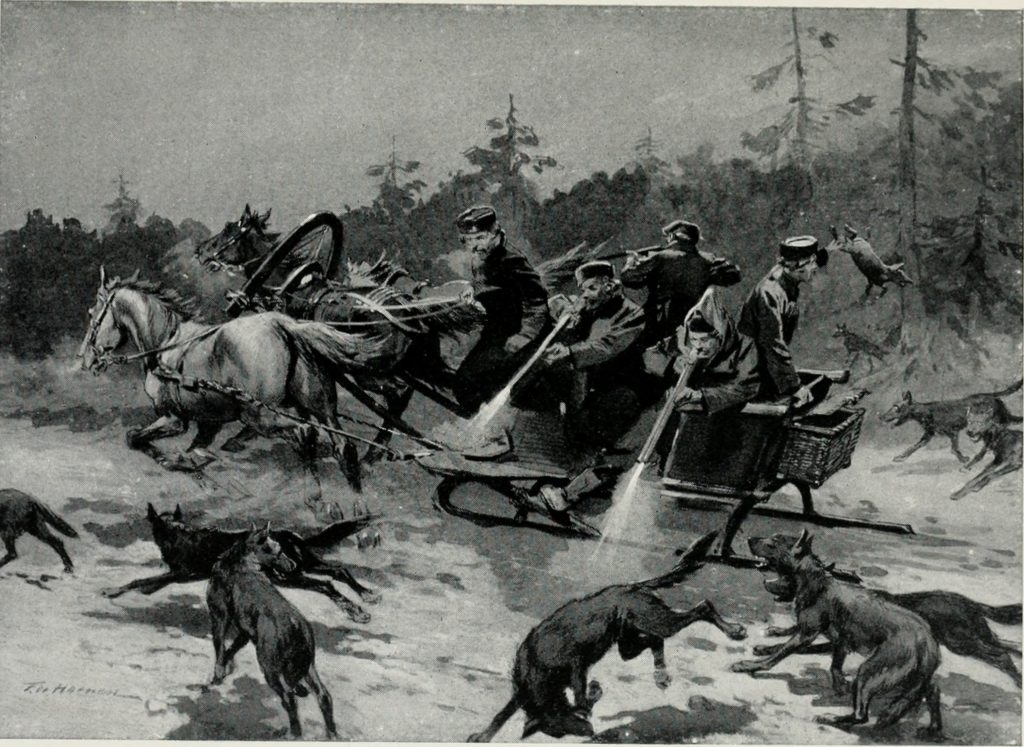

Back in 2016 I had a translated story published by The Cossack Review. I’ve just learnt that this journal exists no more, it has gone the way of a good percentage of literary journals. The story is ‘Joseph Olenin’s Coat’ by Eugène-Melchior de Vogüé, a quirky tale about a lonely man in an isolated wintry part of Ukraine, who loses a coat, finds one, and falls in love with it.

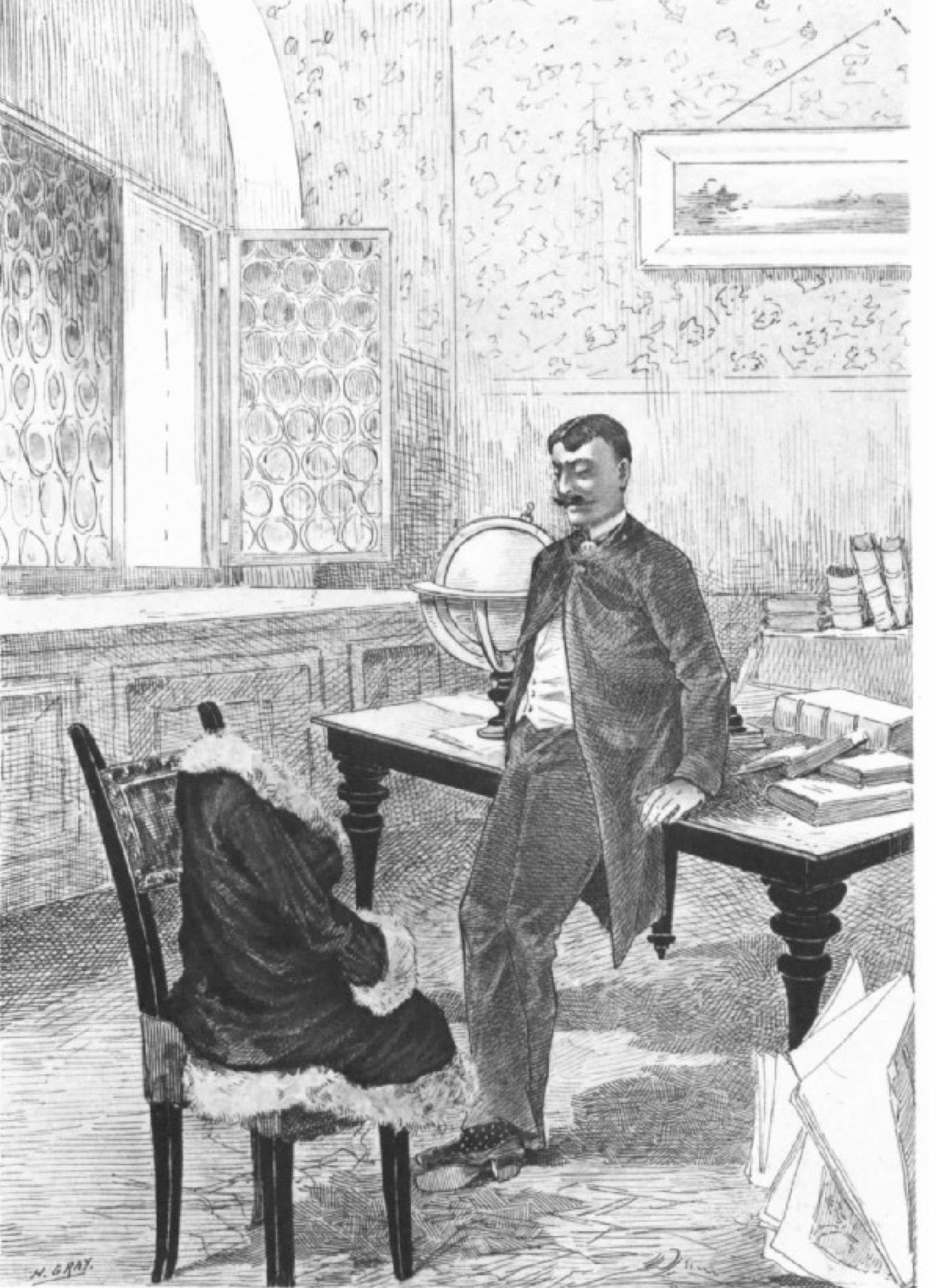

It was originally published in 1886 in an illustrated journal, ‘Les Lettres et les arts’. Who wouldn’t want to read a story with a decorative border round the opening paragraph such as this one by Saint-Elme Gautier? (Click the image to see the detail.) There were several illustrations throughout the story but the best one is ‘Contemplation’ by M.H. Gray showing the poor man gazing at the woman’s coat he’d accidentally acquired and wondering what its owner looked like, felt like…

My translation was published in a print journal and, fortunately, I have a copy of it. It was also available online for a time, but has now disappeared. The editor, Christine Gosnay, had asked me some questions for an interview, and those questions and answers are still there, albeit in a basic format without the styling of the original web site. It would be a good idea, I think, to re-post the interview here.

Patricia Worth: Contributor Interview

May 28, 2016

TCR: What are you reading now?

Patricia Worth: Tales of Hans Christian Andersen translated by Naomi Lewis. And All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr.

TCR: How and where did you find out about de Vogüé’s work?

Patricia Worth: A library at the Australian National University has a collection of old French literature that hasn’t been borrowed for decades. Here I found a small dusty book of short stories by Eugène-Melchior de Vogüé (whom I’d never heard of), and chose it simply for the title ‘Nouvelles orientales’, a title invented by a publisher. Expecting Orientalism and hot Middle Eastern settings, I found instead stories set mostly in wintry Russia and Ukraine. They are nonetheless fascinating. Several had originally been published in de Vogüé’s collection, ‘Les Coeurs russes’ (Russian Hearts), and a few were translated in 1895 as ‘Russian Portraits’, a translation which did not include “Joseph Olenin’s Coat’.

TCR: Do you plan to translate any of his other stories?

Patricia Worth: I have translated all the stories in ‘Nouvelles orientales’.

TCR: How long did it take you to translate “Joseph Olenin’s Coat’?

Patricia Worth: As I translated the whole book of ten stories, it’s hard to say how long it took me for each one. But, in general, a rough translation of a short story takes me a few days, and then I polish it for a few months, researching details, asking experts for help and getting people to read it and comment.

TCR: Can you describe your process for taking somewhat antiquated work from one language to another, especially with respect to diction and tone?

Patricia Worth: De Vogüé was strongly influenced by Russian authors like Turgenev, and as a literary translator I have long admired Constance Garnett’s translations of Turgenev’s short stories, so I looked to her example when working on de Vogüé’s stories. For Garnett, less is more. She generally writes with fewer syllables and fewer words than other translators. In Turgenev’s “The Tryst’, for example, Garnett writes “the hue of an over-ripe grape’, where a modern translator writes “which resembles the colour of overripe grapes’; or “Not one bird could be heard’, against “There was not a single bird to be heard’. When I consider the readability of my work, hers is the brevity I come back to.

It’s also good to read modern English authors who have created a sense of another time, like Joan Lindsay and her ‘Picnic at Hanging Rock’, published in 1967 but set in 1900, or J. L. Carr, ‘A Month in the Country’, published in 1980 but set in the years after the Great War. These two have also taught me much about making every word count.

Of great help, too, are readers of my drafts who are familiar with older texts. For “Joseph Olenin’s Coat’ a French friend pointed out the subtle words that alert a native speaker to the spirit in the coat that enters Joseph’s life and obsesses him against his will, and to the superior tone used by the Countess when addressing Joseph. A local writer and translator of Proust who reads most of my work also offered corrections and suggestions to take my diction back in time (for example skating, not ice-skating).

When I find myself stuck in today’s English, help is available by entering a French phrase into a search engine which can trigger old pieces where the words are used in other contexts. The search might even produce helpful French translations of English classics by, say, Dickens or H.G. Wells, and then I look for the phrase in the original, and use a variation of it. There are also a number of French and French-English dictionaries from the 1700s and 1800s freely available online; these are invaluable for learning the former meaning of a word. Of course, I read, read, read nineteenth-century English literature, the Brontë sisters and Thomas Hardy among many others.

TCR: Who has had the biggest influence on you as a writer?

Patricia Worth: For translation, I’ve been influenced by the various translators of Hugo’s Les Misérables as well as Constance Garnett’s translations of Russian literature. For writing in general, I find Charlotte and Anne Brontë’s novels compelling, and hold them as my standard. I was also influenced by my father, a volunteer soldier, who wrote poetry in Egypt in 1941.

TCR: What authors do you re-read?

Patricia Worth: The Brontës.

TCR: What is your next writing project?

Patricia Worth: I’m presently translating a book of French fairy tales.

***

PS: I’m surprised to read that I was translating the fairy tales when I responded to this interview. Those fairy tales, Stories to Read by Candlelight, are presently on the production line and should be appearing some time before June this year. I’d forgotten how long I’d been working on them.

***

![Winter Tales by [de Vogüé, Eugène-Melchior]](https://images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/51TY38aUGhL.jpg)