There were 700 or 800 of them at least. Of medium height, but strong, agile, supple, framed to make prodigious bounds, they gambolled in the last rays of the sun, now setting over the mountains which formed serried ridges westward of the roadstead.

Opening lines of Gil Braltar by Jules Verne, 1889, translated by I.O. Evans, 1965

Can you guess what they are, these gambollers? Perhaps if you’ve been to Gibraltar you’ll know they are monkeys. The title of this fantastical tale, ‘Gil Braltar’, is also the name of the main character, an ugly Spaniard who resembles the macaque monkeys that possess the great Rock. To convince them to follow him as their leader, Gil dons a monkey skin, fur side out. He tries to recapture Gibraltar from the British, but fails, defeated by an Englishman, General MacKackmale, a pun on the French words macaque mâle.

When Verne’s science fiction/fantasies were first published in French, they were quickly followed by English translations. But not this one, which wasn’t translated until 1965. Hmmm. Clearly, Verne’s satire on the British claim to the Rock didn’t impress British publishers. But like many things that at first feel unpleasant, we find a few decades later that perhaps there are interesting elements, after all.

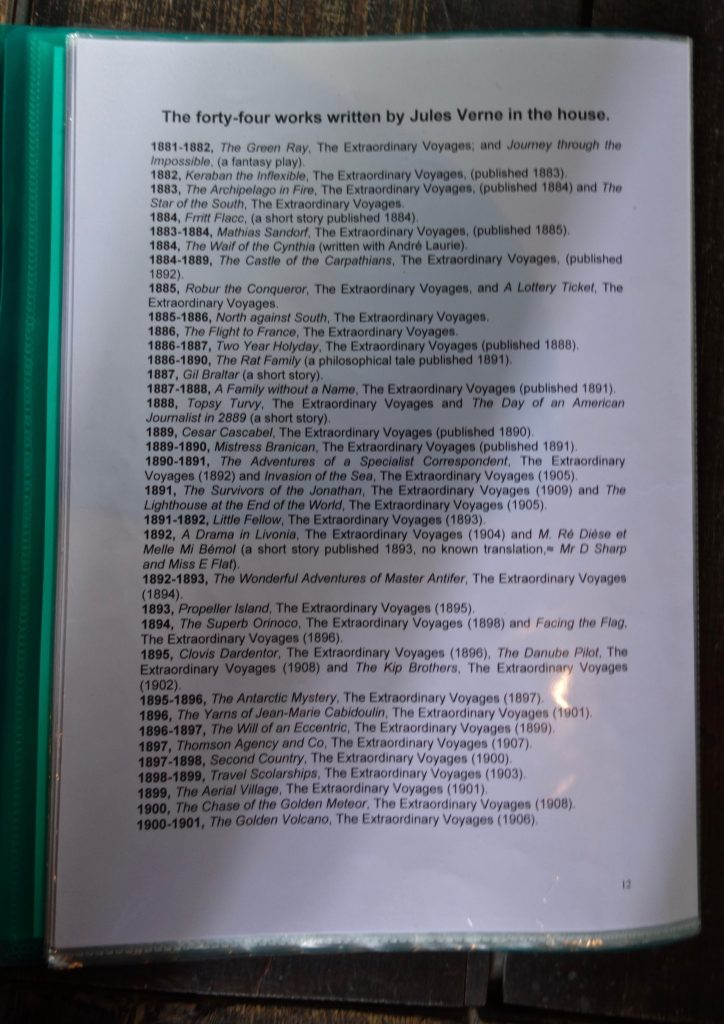

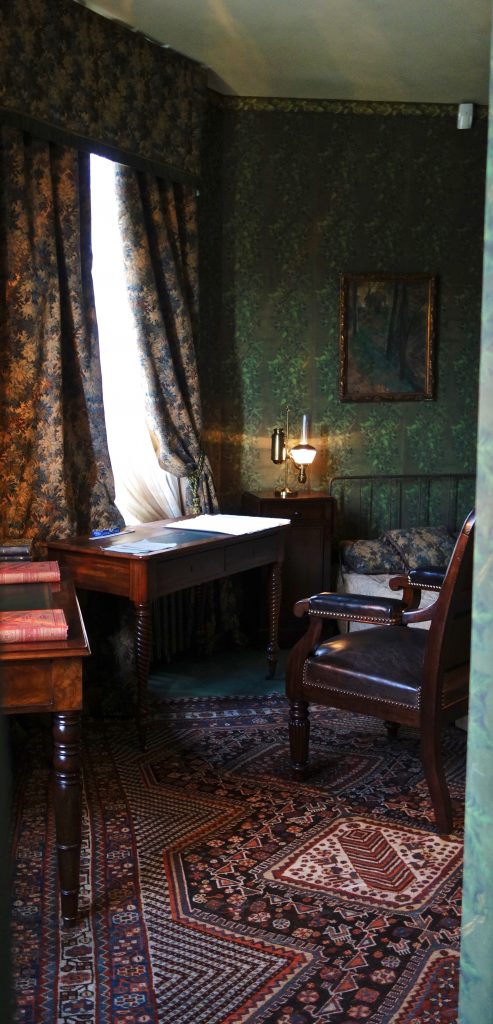

In my previous post I wrote about Dr Trifulgas. This and Gil Braltar were both written by Jules Verne in his house in Amiens, France, which I visited earlier this year. While the ground floor is elegant and nothing out of the ordinary for a 19th-century French house, a climb up the spiral staircase takes you to Verne’s writing world, where at the top of the stairs there is an improvised ship’s deck, a larger space filled with exhibits, and a compact study-cum-bedroom where Monsieur Verne wrote many of his famous stories. There’s even a list in English of stories written in this house – if you look closely at the photo below, you’ll see Dr Trifulgas (Frritt Flacc in French) and Gil Braltar.

It’s funny that I’ve read so many stories by Jules Verne recently; I once had no time at all for science fiction. After visiting his house and seeing the upstairs space filled with books and maps and puppets and posters, not forgetting the ship’s deck, I had a whole new appreciation for the work that goes into producing an imaginative piece of literature. As a translator, I had not thought long about it until then.

*