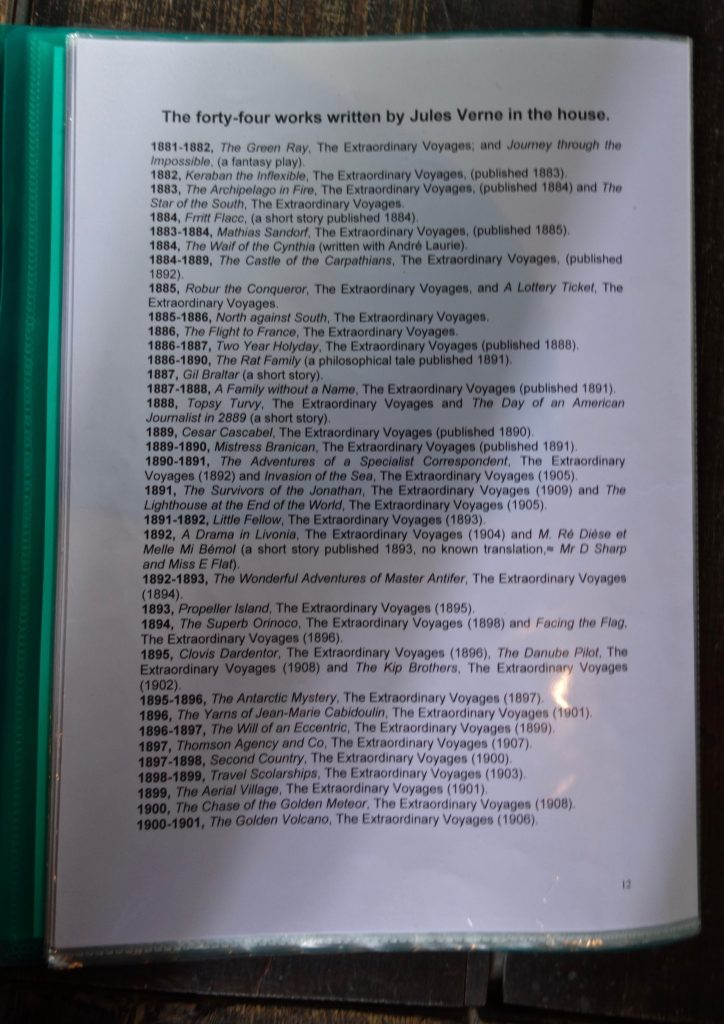

Soon a story written by Marcel Aymé, Le Loup, translated into English as The Wolf (by me) will be out in an illustrated edition of Delos Journal. The editor’s decision to illustrate it really blew me away. Life for me is much easier to bear when I’m reading an illustrated book.

Now, in anticipation of the Delos wolf, I’m wondering whether he’ll be fierce or deceptively gentle. In my tall piles of books about fairies and fantasy there are many wolfish images from the 19th and 20th centuries that leave me dreaming about ideal illustrations for my translated tales. Today I pondered over a few of the images that have taken my fancy.

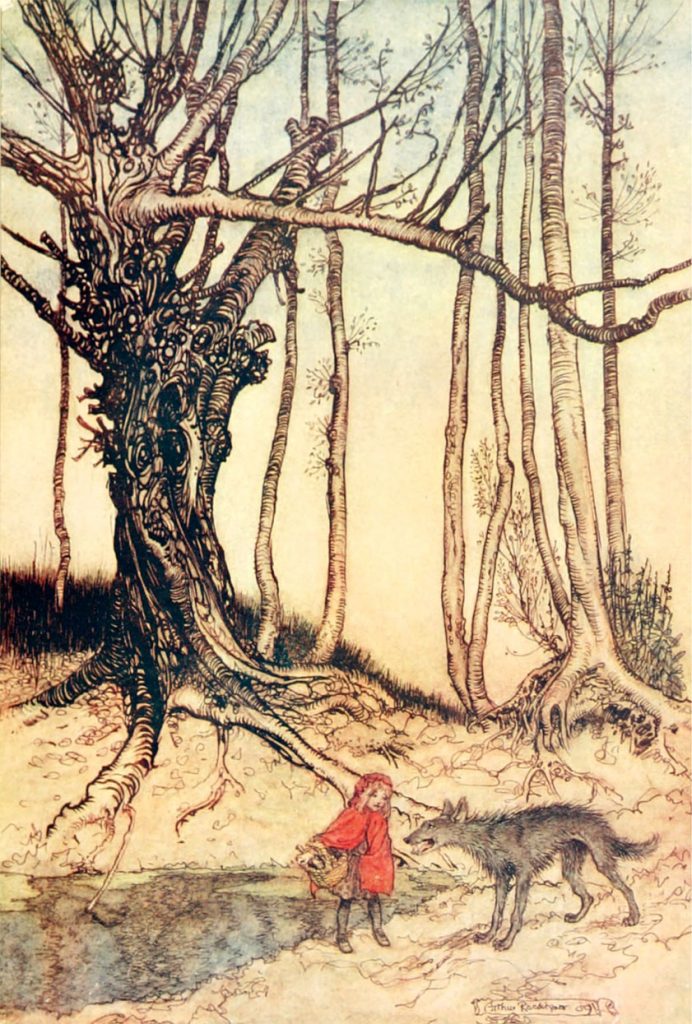

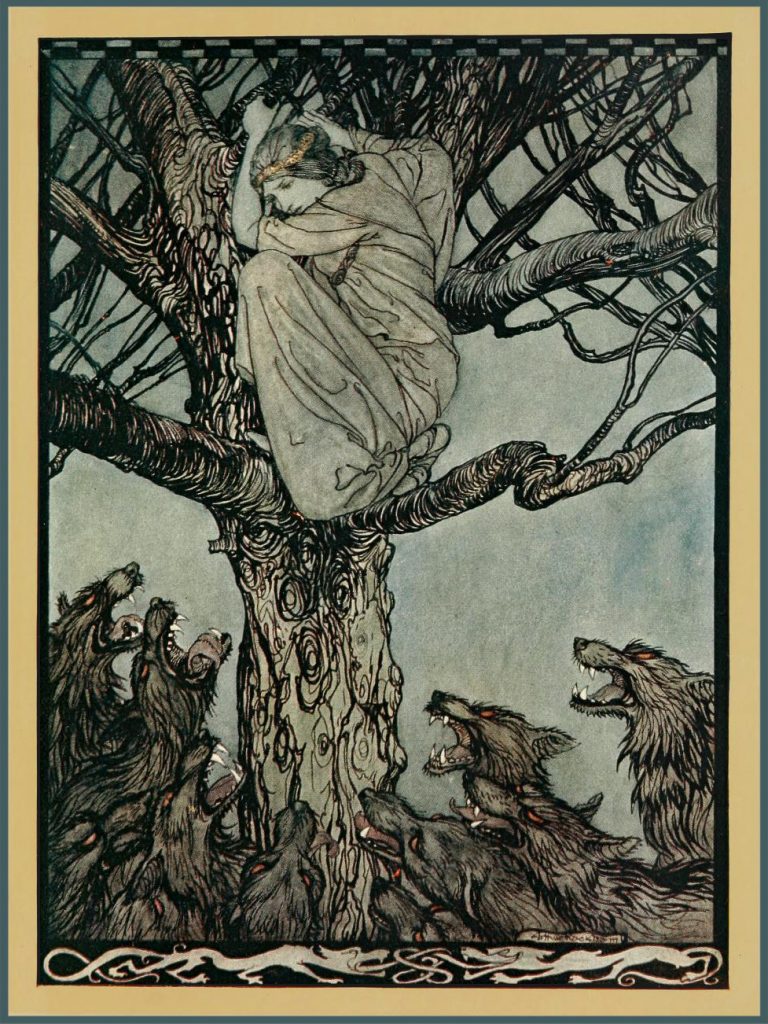

Illustrated fairy tale collections published for children since the 19th century are usually delicate, refined, unreal and rarely violent despite the brutal stories they represent. Take, for example, Arthur Rackham’s fine drawing in which the wolf doesn’t look particularly threatening:

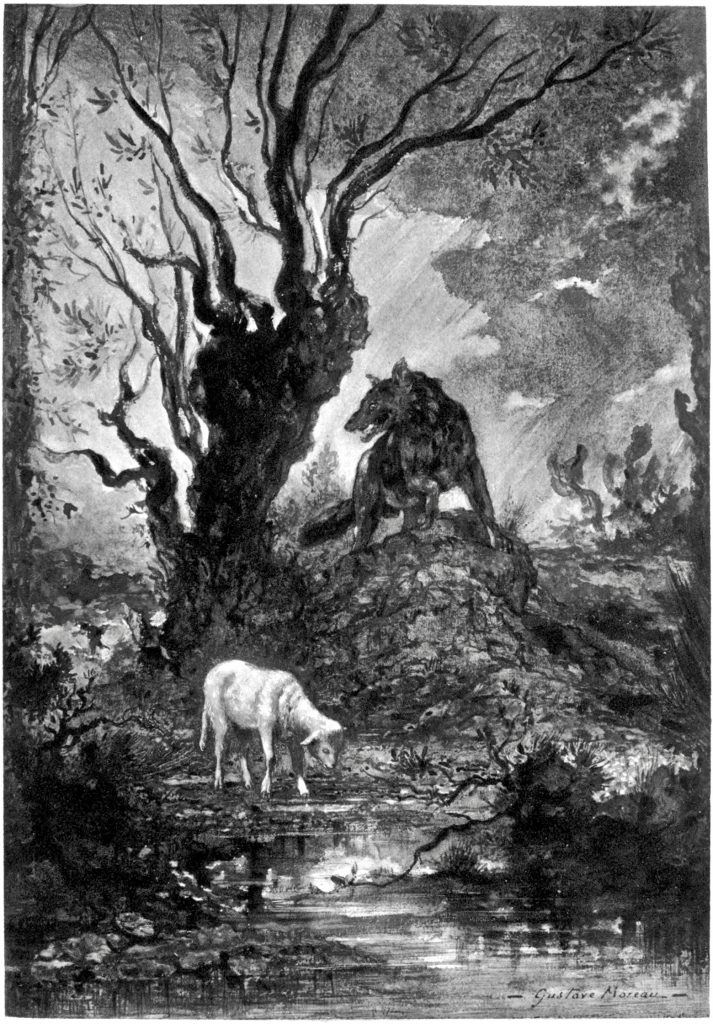

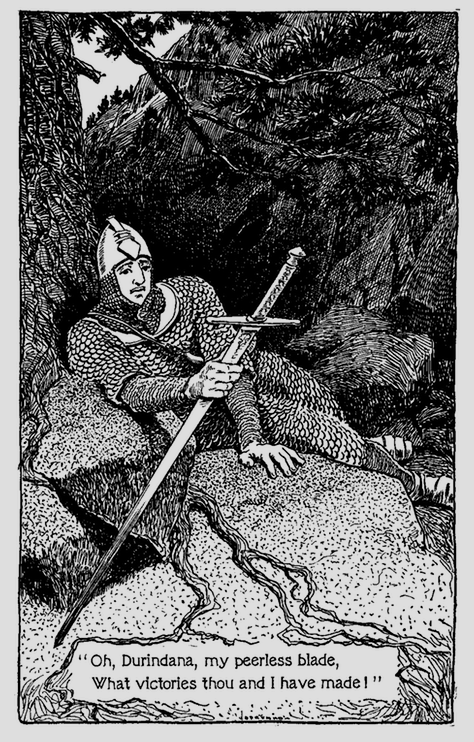

Aymé was clearly inspired by that guilty wolf we’ve all met in fables and fairy tales if not in real life. In his little story (which I hope you’ll read when it comes out later this year…) two little blonde girls remind their visitor, the wolf, that he’s never been good, he’s always been bad, and as an example they evoke La Fontaine’s fable about the wolf and the lamb, depicted here by Gustave Moreau, where the wolf appears a little hungrier than Rackham’s:

Aymé’s wolf claims to have changed his ways, he denies he ate Little Red Riding Hood’s grandmother though we’ve been led to believe otherwise by this illustration by another French Gustave. Gustave Doré depicts the moment just before the wolf is about to take his first bite, his long tongue lolling as Grandma realises her terrible fate.

While Doré’s image would be a wee bit scary for a child, a stretch of the imagination might be needed to associate animal instincts with Shaun Tan’s little sculpture. Today I discovered his illustration for a very abbreviated version of ‘Little Red Cap’ by the Brothers Grimm. It has none of the pretty trees and tendrils of Rackham’s image, but neither does it have the drooling wolves of Moreau’s and Doré’s sketches. It’s composed of two tiny solid characters crafted from clay with the simplest features.

My favourite wolf image this week is one which depicts the kind of wolf you’ll find at the end of Aymé’s story. It’s by Rackham but it’s a far scarier drawing than we saw above. Here, Becfola, of an Irish fairy tale, is perched on branches just out of reach of hungry mouths. It instils in me exactly the kind of fear I’d have if a wolf had chased me up a tree.

I’m anxiously awaiting the appearance of Aymé’s The Wolf. You can be sure I’ll be blogging about it the moment I hear it’s out.

*

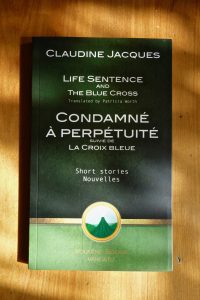

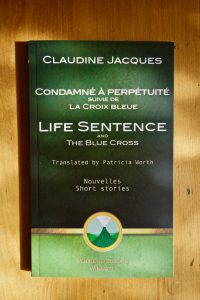

Life Sentence was published last year in Southerly Journal (Sydney University), and now it’s available in this little edition from Volkeno Books, Vanuatu. This is the second bilingual book published by Volkeno that includes Jacques’ original and my translation. The first was

Life Sentence was published last year in Southerly Journal (Sydney University), and now it’s available in this little edition from Volkeno Books, Vanuatu. This is the second bilingual book published by Volkeno that includes Jacques’ original and my translation. The first was