Tuesday, July 23rd. – Am aroused by violent knocking at the door in the early gray dawn – so violent that two large centipedes and a scorpion drop on to the bed.

First line of A Hippo Banquet by Mary Kingsley, 1897

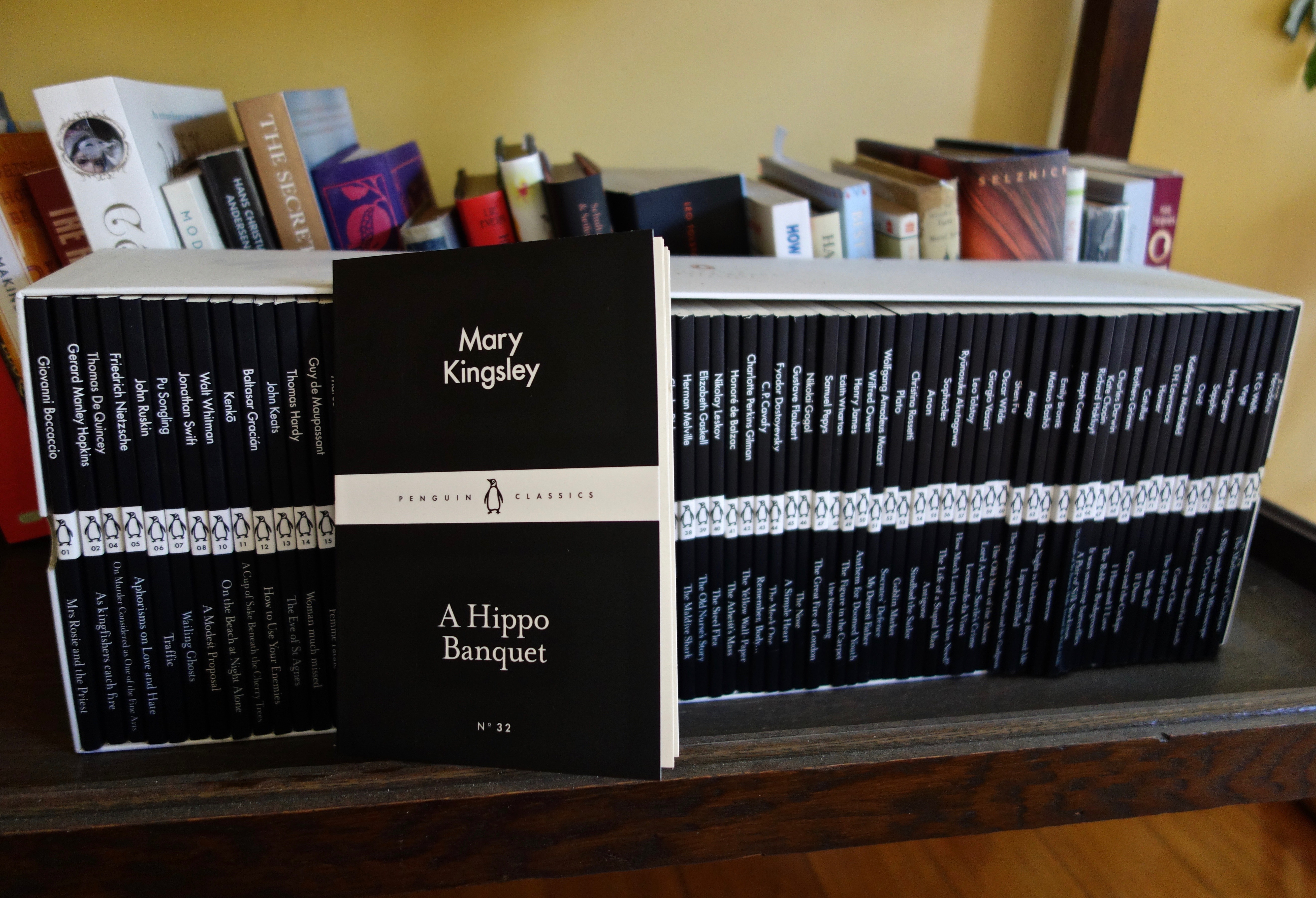

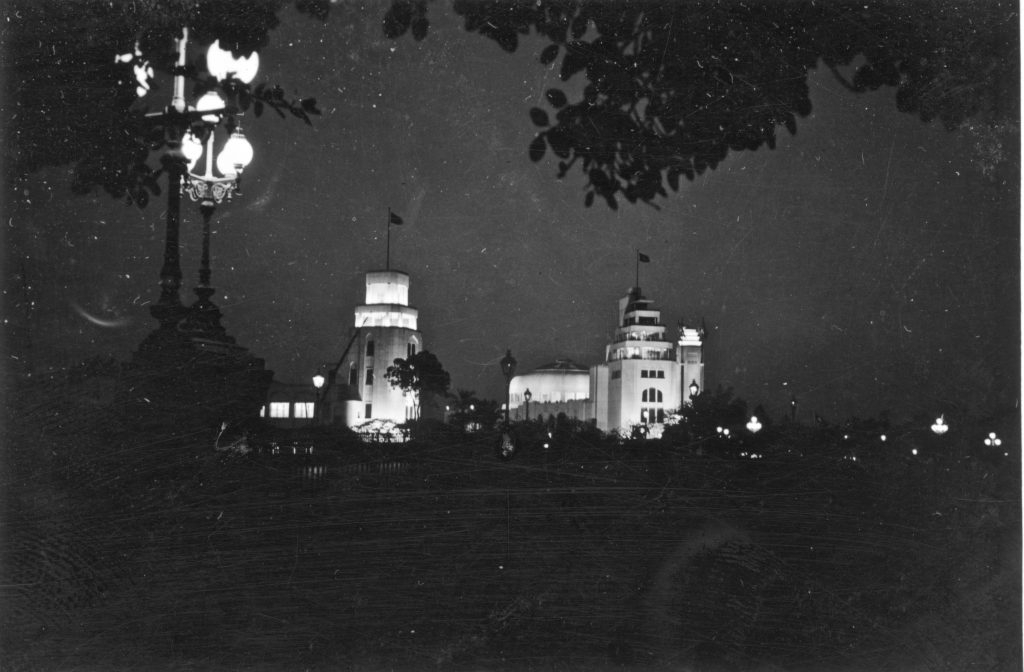

This is the first line of the first story in a small book, A Hippo Banquet, published by Penguin as no. 32 of 80 Little Black Classics. The line certainly drew me in, fearful as I am of bugs dropping down on me in my bed. Quite the contrast is this fearless English woman, Mary Kingsley, who lived in West Africa in the 1890s and wrote of her life there in Travels in West Africa from which this little black book was made.

The hippo banquet occurs at night when hippos graze on hippo grass. Mary has gone for a canoe ride alone in the middle of the night because she can’t sleep (mosquitoes and lice in the bed…), and it’s then she comes upon five hippos feasting.

The first line of the whole work, Travels in West Africa, is much longer but equally compelling and worth quoting:

“The West Coast of Africa is like the Arctic regions in one particular, and that is that when you have once visited it you want to go back there again; and, now I come to think of it, there is another particular in which it is like them, and that is that the chances you have of returning from it at all are small, for it is a Belle Dame sans merci.”

La Belle Dame Sans Merci is a poem written by John Keats in 1819, in which the Belle Dame is at once a figure of love and fantasy, death and decay.

*