Five black and white photos from my everyday life. Day four: labyrinth.

How I longed to run into this mess of twisting branches and climb through from one end to the other. But I’m too old. And I still have my pride.

A quiet place.

Five black and white photos from my everyday life. Day four: labyrinth.

How I longed to run into this mess of twisting branches and climb through from one end to the other. But I’m too old. And I still have my pride.

Five photos of my everyday life. Day three: frond.

Toto, I’ve a feeling we’re not in Canberra any more.

Inspiration from anevolvingscientist.org (on his Facebook page).

Black and white photos of my everyday life. Day two: Fountain.

The Captain Cook Memorial Jet in Lake Burley Griffin, Canberra, shoots water 152 metres high for about four hours a day. In moderate wind the fountain spray forms a transparent curtain across the lake. In strong wind it’s turned off to prevent a water hazard on the nearby bridge.

Photo taken during a visit this week to the National Library to read Pierrots on the Stage of Desire, a history of 19th-century French pantomime.

Inspiration from anevolvingscientist.org (on his Facebook page).

Five photos of my everyday life, in black and white. Day one, fungus.

My gardens have just had a professional makeover. The gardener re-made four identically shaped gardens with the same range of plants repeated in each. But in one of them, under and around a grevillea, a leathery tan fungus is growing, apparently not a bad thing. It’s possibly a saprophytic cup fungus feeding on the rotting forest litter used as mulch. I just spotted it a couple of days ago. It’s a real head-turner and typically evokes this reaction: Whoa, what’s that?

Ken, anevolvingscientist.org, came up with this photo challenge. Many thanks!

*

Some years ago I scanned hundreds of photos from an album my father brought back from the Middle East in 1942. The original snaps are small, about 2″ x 3″, so I’m fascinated by the detail I now see in these scanned and enlarged photos, such as the people on the right in the image above. The caption for this picture says “Col. Gee, Syria”. Nothing about the other guy. However, it’s uncertain whether it was taken in Syria or Lebanon. The photo below, the ski school for the soldiers, is marked as located in Syria when in fact it was in Lebanon.

Easy mistake to make, since the Australian soldiers were sent to train in Syria in the winter of 1941/42, but from there they went to Lebanon to train to fight in snow country. A disused chalet near Bcharre in the Lebanon ranges was turned into a ski school. It was pretty hard on the Australians, used to extreme heat but not extreme cold.

So much snow. The magnificent cedars of Lebanon form the only contrast in this black and white image.

*****

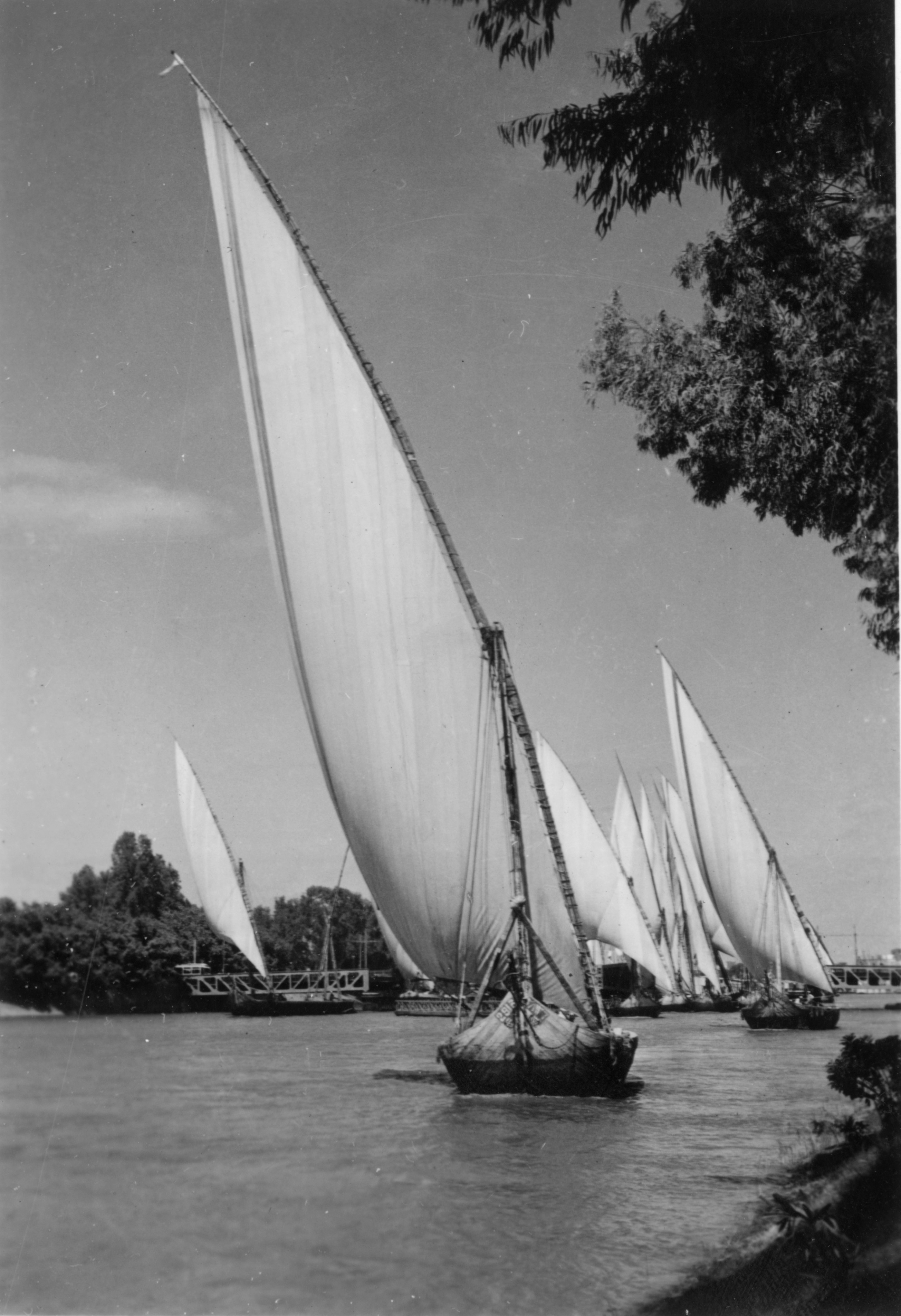

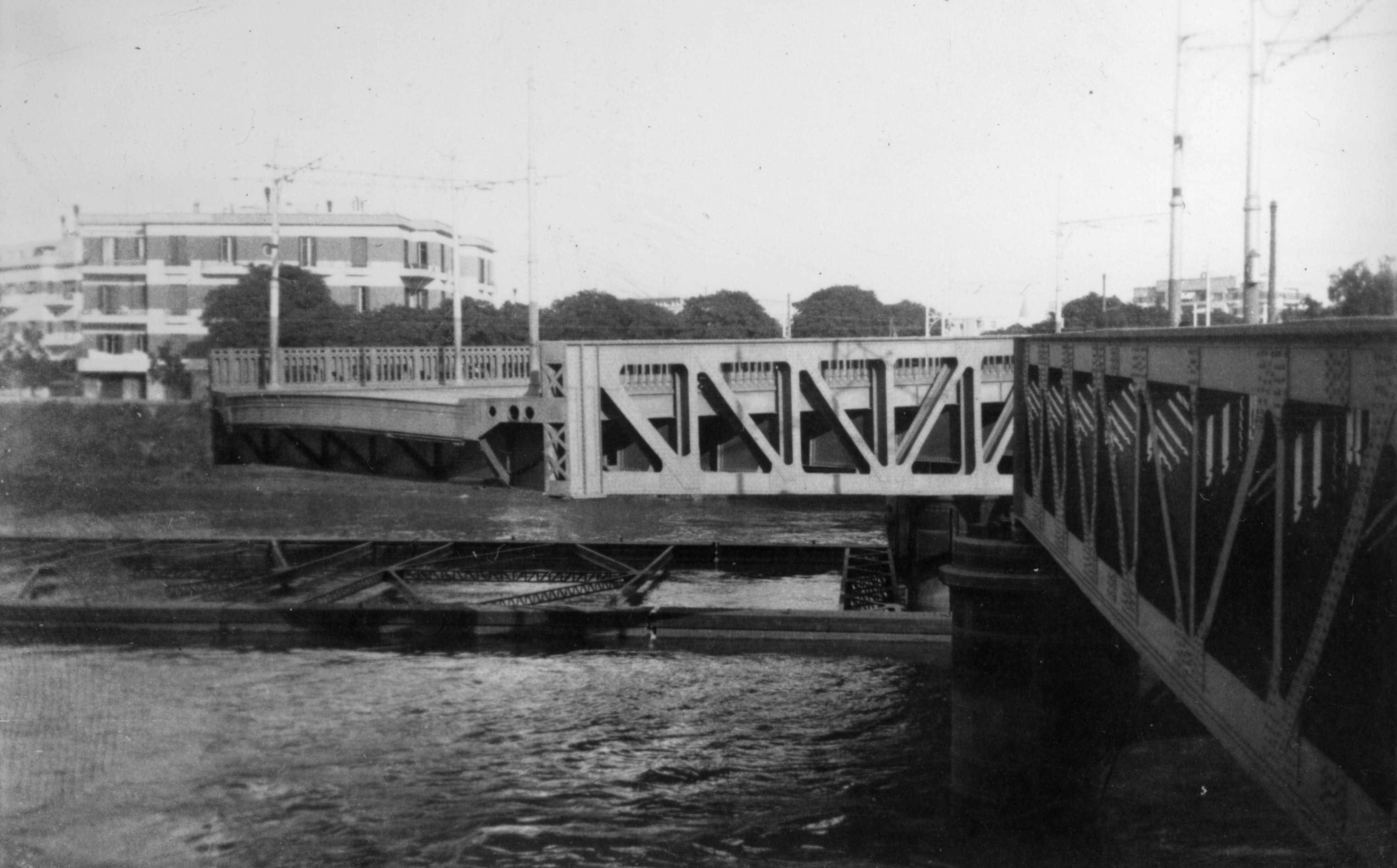

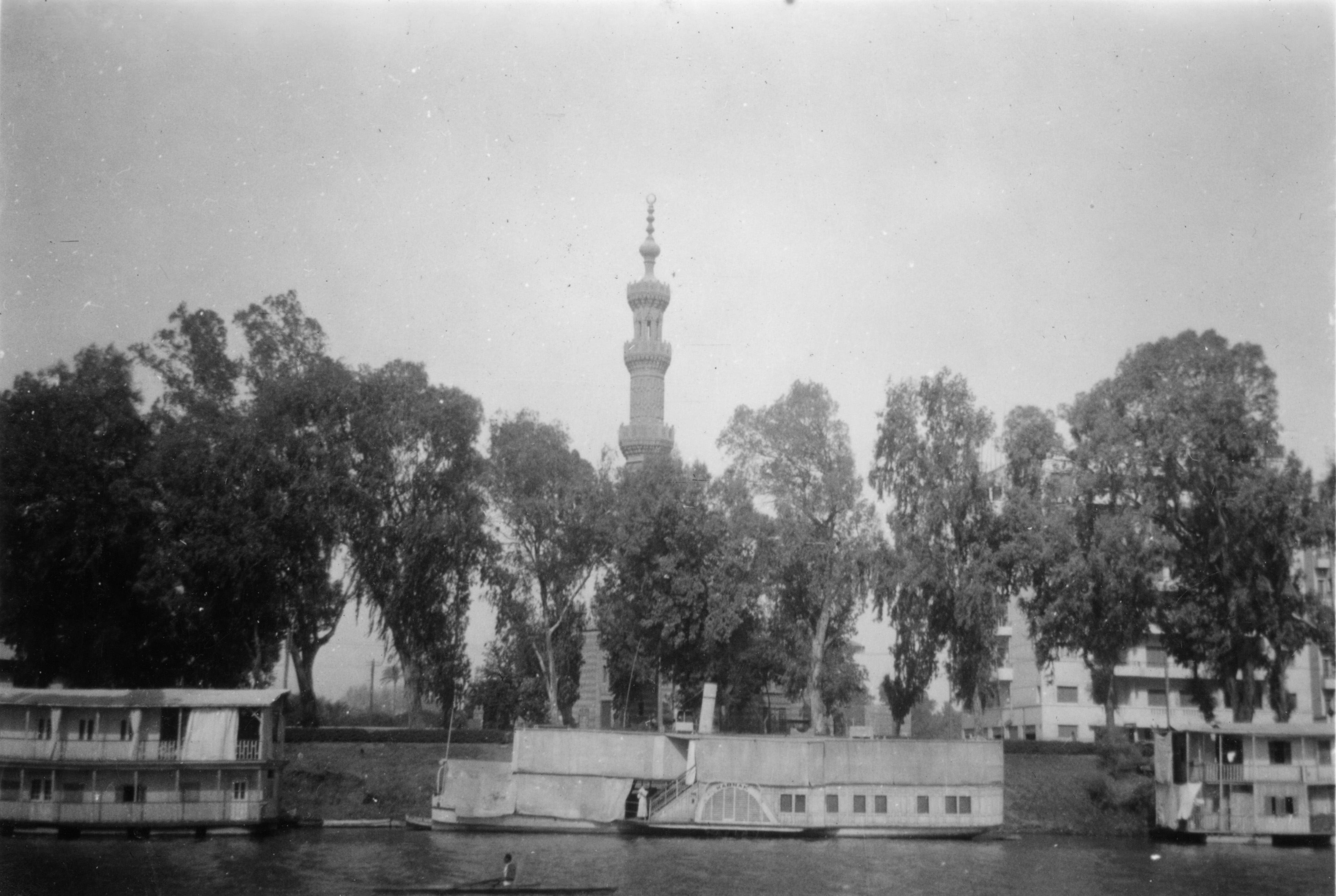

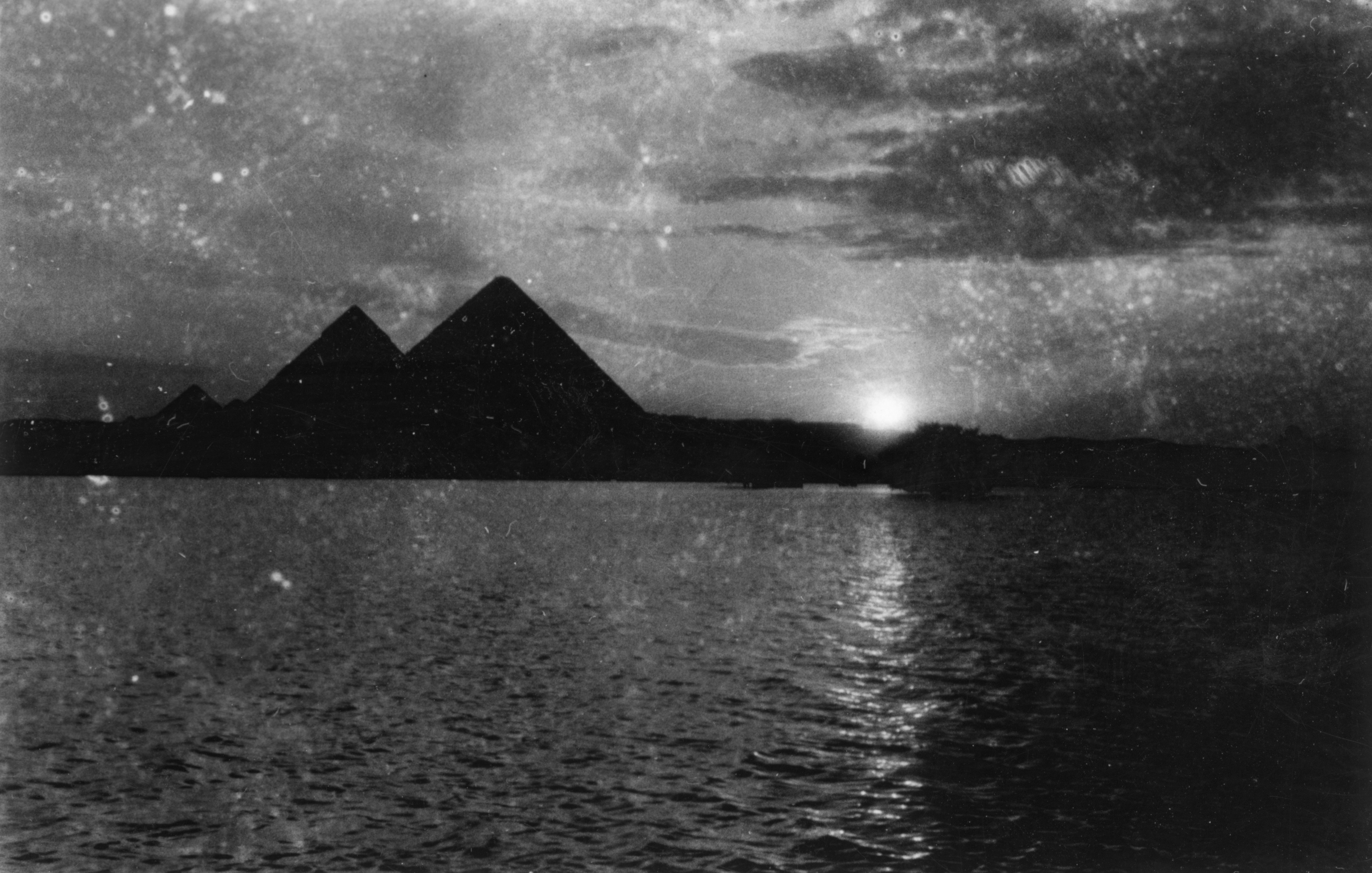

A reader of this blog, a maritime archaeologist writing a PhD, expressed an interest in some of the photos I’ve posted here over the past five years, especially images of the Nile and its boats. So this post is about the Nile River, Egypt, in a particular period, 1941/42. The photos are from my father’s album, from a time he was stationed there for seven months with the army (not counting the couple of months to get there and back). He took photos and swapped photos with his mates, stuck them in an album and left them for his family to do what they wanted with them. Many of these photos have been on this blog before, with a couple of exceptions. Where there were captions beneath the photos in the album, I’ll repeat them. Where there was none, I’ll write what I know, if I know anything. The photographers of these photos are unknown. Some were taken by my father, some were not. I don’t know which is which.

I love all my black and white 1940s photos, but I totally love the feluccas and never tire of looking photos of them. Thanks, my reader, for asking me to take another glimpse into 1940s Nile history.

*****

My father captioned this photo in 1942 ‘Dud bombs’. But judging by the rubble almost covering the small building at the bottom right, some earlier bombs had done the job they were made for.

It’s an odd photo that seems to have a part of another photo laid over it; the man looking at the dud bombs is transparent! The hill of rock behind him is visible through his face…

The WordPress Weekly Photo Challenge this week is to find an image that evokes danger, so I immediately thought of this one from Dad’s war album of photos from Egypt and Libya. I don’t have a clue about bombs, exploded or unexploded. But these dud bombs were probably a source of danger.

This week’s WordPress photo challenge title is The Road Taken, which is not the road taken by the poet Robert Frost in his poem, The Road Not Taken.

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood and Frost made a decision to take the grassy road, the one that wanted wear, the one less travelled by. Ages from then, he told how the road taken had made all the difference. The poem’s title is a careful play on its message – The Road Not Taken, for him, is the one everyone else took.

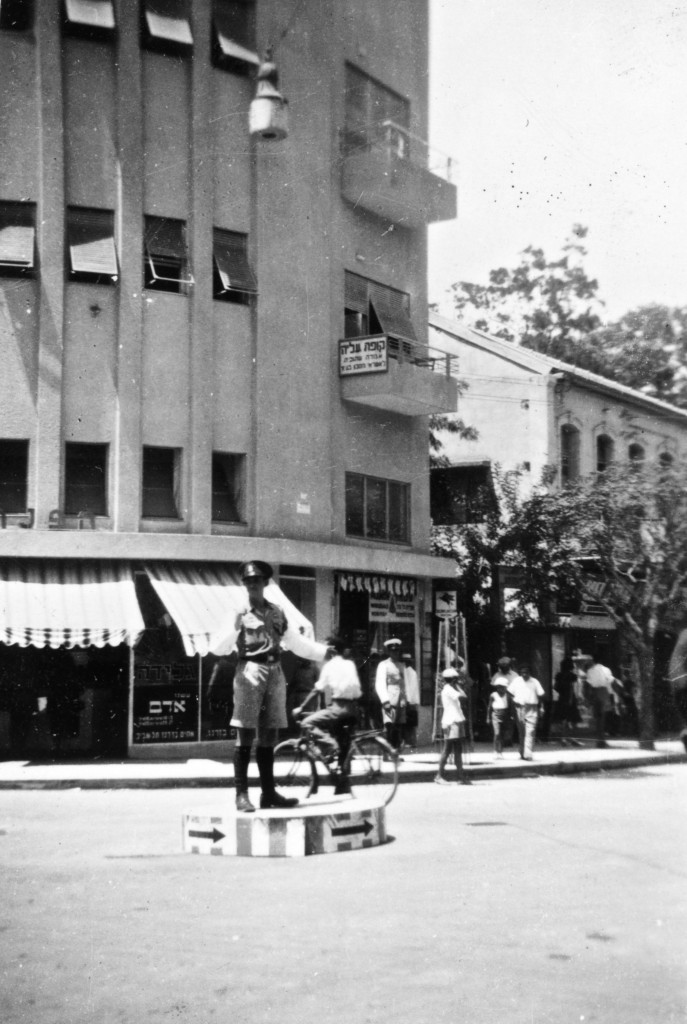

Here’s an image of a road taken in Israel, a road where no grass grows, where tarmacadam has been laid to avoid the mess of wheel ruts. The photo is from my father’s war album; he called it “Point duty Tel Aviv”. This traffic cop is a living traffic light, bang in the centre of converging roads, with only his arms and two painted arrows to give people direction. Clearly it’s a road that needs some form of traffic control, and indeed the officer seems to be looking at something coming his way.

Still in Israel, here’s a road that’s long and winding. The Road of the Seven Sisters was constructed during the time of the British Mandate of Palestine (1920-1948), and apparently there are seven bends in the road, though many disagree. I’ve read it’s hairy to drive it, but, at the time, it was the only approach for cars coming to Jerusalem from Tel Aviv. It looks quite bleak in this black and white image but recent colour photos show vegetation now softening the roadsides.

(The photographer might have been my father or it might have been a friend; soldiers commonly swapped photos.)

Unlike Robert Frost, it’s not often I find myself in a wood, and even less often in a yellow wood here in a country where native forests are perpetually green. But if I did, and if I came to a fork in its road, I would not take a path if it needed traffic control, or if it were a steep winding road of hairy hairpin bends built for army vehicles. Like Frost I would go where no one else that day had trod.

“Two roads diverged in a wood, and I —

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.”

If The Road Not Taken is new to you, take a brief moment to read it. It’s in many places online, here for example.

There’s this song that goes:

Son, in life you’re gonna go far

If you do it right

You’ll love where you are.

Just know, wherever you go

You can always come home.

…

Son, sometimes it may seem dark

But the absence of the light is a necessary part

Just know, you’re never alone

You can always come back home.

It’s 93 million miles, sung and partly written by Jason Mraz. It’s a song about something so much bigger than us, yet without which we cannot live. Though we are incomprehensibly far from the sun, its light and warmth after travelling all that way are perfect for us and our planet.

My son in Germany sometimes feels likes he’s millions of miles from home, but fortunately he’s not. He likes this song because of the reminder: You’re never alone. Once, when he was still living with us, I had a migrant English student come for a lesson and my son played 93 million miles on his guitar for her. We all sang it together, and by the end we felt like every one of the world’s problems was solvable!

93 million miles from the sun

People get ready, get ready,

‘Cause here it comes, it’s a light

A beautiful light

Over the horizon into our eyes.

Here’s my son when he was still in Australia, enjoying solitude between a rock and a hard place on ‘Ben’s Walk’, a riverside forest track in Nowra, New South Wales. It’s an image of solitude, a moment when he was on his own, contemplating the river view. Although, as the song says, ‘You’re never alone’: his dad was round the other side of the rock and I was outside the gap with a camera!

Actually, he’s not alone in Germany either, for he has his wife, Mrs Amazing. But this post is for him in those hours when she’s away doing amazingly astronomical things and he’s physically alone. It’s a bit of electronic interaction that might, just might, momentarily curb the negative side of his solitude.

Thanks WordPress for the challenge.

A flâneur? In a 19th-century dictionary he’s a loiterer, a lounger, an indolent man spending his time idly. In contemporary dictionaries he’s a loafer, an idler, a stroller, a dawdler, an ambler, a laggard.

So many options to describe a man who has no timetable, no destination. Doing nothing, going nowhere. Apparently.

Yes, a flâneur in French is a man. But a woman, too, can loiter and lag. She’s the flâneuse.

Strolling the streets of my city, observant, detached, armed with a small camera, watching for someone who’s not like the others, I occasionally play the part of the flâneuse, capturing a few colourful characters in this city. But their colours can distract. Here I’ve removed them.

I love hair. My trigger finger itched when I saw this man who hasn’t seen a barber for some time. I stopped and loitered as flâneuses do. It was lunchtime and his eye was on a small charity barbecue stand while my eye was on his hair. I bet he’s an interesting bloke.

Within minutes I came across another one who avoids the barber. With his long white hair and beard and his black scarf and coat, he loses nothing in a conversion to black and white. He’d been to the sausage-sizzle stand and was sitting down for a lunch break.

Not far away I spotted another long male ponytail, plaited. Whatever he was saying, it amused his companions, the woman handing out The Big Issue free magazine and the bloke with a can of Mother and an attitude.

On my way home my ears were tickled by a busking guitarist who plays here frequently and brilliantly. A busker with a ponytail. His head was bent low over his guitar, eyes fixed on the strings, but when a passer-by threw a few coins into the guitar case and stopped to watch, the guitarist looked up and sort of smiled, as tickled by his one-man audience as I was by his music. I dropped some money into the guitar case. He had earned it.

The Daily Post challenged us this week to become flâneurs. As I ambled and wandered – not aimlessly nor idly – observing people in front of me, across the street, under a tree, against a wall, I concluded that not all of us are forgettable.

***