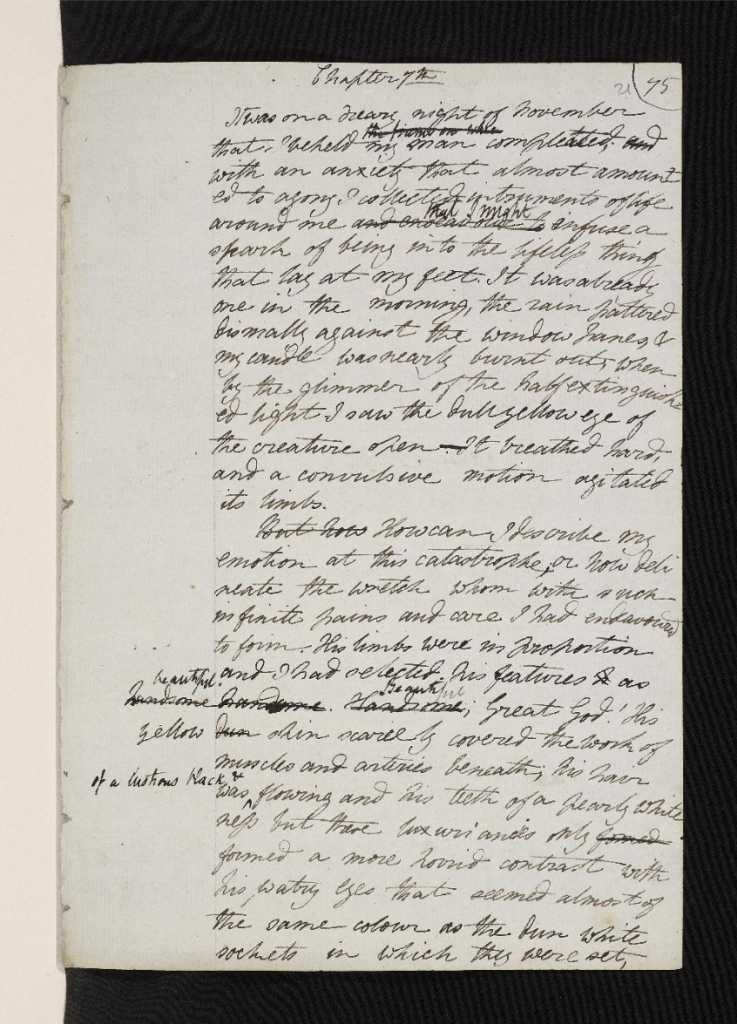

It was on a dreary night of November that I beheld my man completed; with an anxiety that almost amounted to agony I collected instruments of life around me that I might infuse a spark of being into the lifeless thing that lay at my feet.

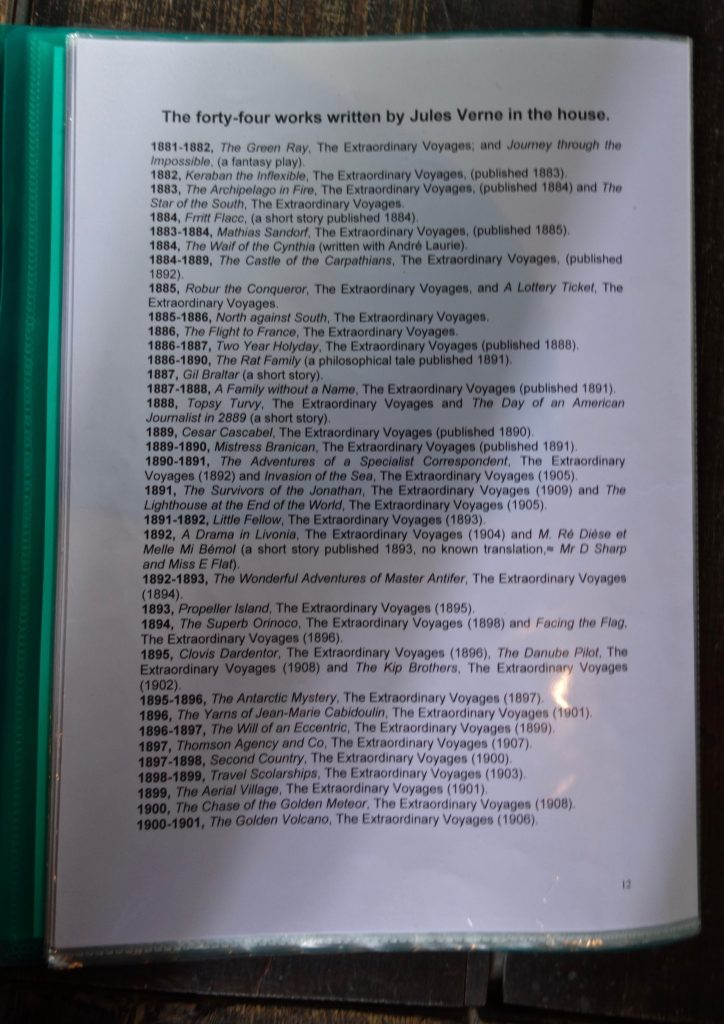

First line of Chapter 7th, Frankenstein (draft), Mary Shelley, 1816, from Shelley, M. W. “Frankenstein, Volume I”, in The Shelley-Godwin Archive, MS. Abinger c. 56, 21r. Bodleian Library, Oxford University

The Bodleian Library has made Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s handwritten draft of Frankenstein available online here. A very interesting resource. The draft contains 87% of the final text as published two years later in 1818. It’s not just an amazing insight into Shelley’s work, but into the many changes of words that occur in any story by all writers great and small. The draft also shows suggestions added by her husband, Percy Shelley.

In the 1818 edition the first words of this chapter are:

It was on a dreary night of November, that I beheld the accomplishment of my toils.

Many will agree with me, I’m sure, that the first draft of this sentence was better. However, flipping back a page we see that the last sentence of Chapter 6 in the draft ended with ‘completed’, so Mary has found another way to begin her chapter to avoid repeating the word. Such is the fiddliness of writing.

On a side note, I was surprised to read a comment on another web site, theverge.com, that the Bodleian Archive has transcribed “the nearly indecipherable text to make it readable”. Nearly indecipherable! I find this observation nearly unbelievable. Since I learnt cursive writing from seven years of age, I have no trouble at all reading Mary Shelley’s handwriting or the suggestions added by Percy. Not teaching or persisting with cursive handwriting in our schools today is one of our great cultural losses.

*