Today it’s a month since I last wrote on my blog. I think that in six years of blogging this has been the longest break.

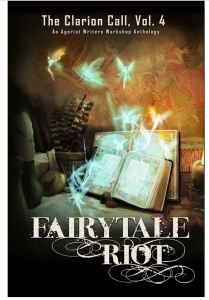

When I reached my hundredth Great Opening Line I had a plan to write about the forthcoming publications of a few of my translated stories. Two journals offered to put my work out there in May and July, but I’m still waiting. The editors aren’t answering my queries so, unfortunately for us all, I’m in the dark. The translations are ‘The Lame Angel’ and ‘Tears on the Sword’ by Catulle Mendès’. I’m particularly hoping the latter will eventually appear in an anthology: Fairytale Riot produced by the Agorist Writers’ Workshop. They have a delightful cover ready, which looks promising:

Translating stories is hard hard work. The first draft is easyish, then there are months of redrafting and tweaking before submitting them to publishers and journals. What follows is a long wait. And while I wait I translate more stories: draft, redraft, tweak, submit. And after that, there’s marketing and promotion… When an editor promises to publish a story and then doesn’t deliver, it’s hard to know whether to promote or forget. Ever the optimist, I’m going to promote another project: Stories to Read by Candlelight.

My translation of Jean Lorrain’s small book of stories, Contes pour lire à la chandelle, was accepted by Odyssey Books back in September 2017, and I’ve now discovered my name on their list of forthcoming publications for September 2018. That’s next month!

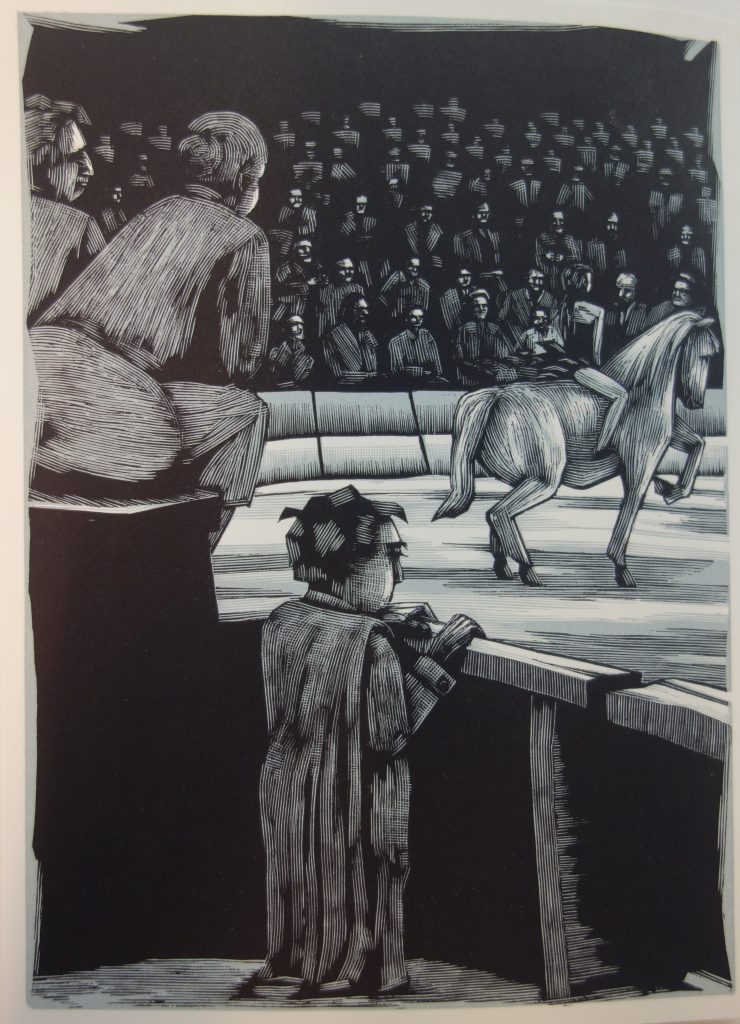

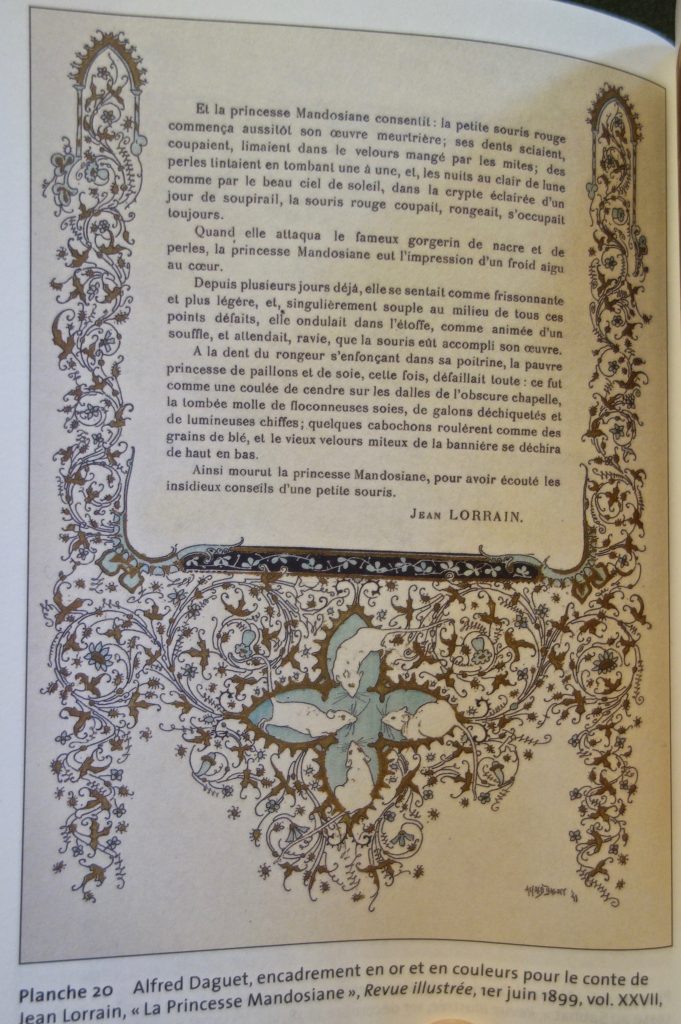

It will be illustrated, which is a bit thrilling for me, since the stories are 19th-century fairy tales, some of which I’ve read in illustrated 19th-century journals, as you see in the example below, and which I’ve imagined in a 21st-century edition. It was very exciting when the Odyssey Books editor, Michelle Lovi, offered to decorate the pages of the new book.

I’ll keep you posted on any of my work that makes it out into the wider world. All going well, there should be a new book of old tales available soon in bookshops, real and electronic.

*

Life Sentence was published last year in Southerly Journal (Sydney University), and now it’s available in this little edition from Volkeno Books, Vanuatu. This is the second bilingual book published by Volkeno that includes Jacques’ original and my translation. The first was

Life Sentence was published last year in Southerly Journal (Sydney University), and now it’s available in this little edition from Volkeno Books, Vanuatu. This is the second bilingual book published by Volkeno that includes Jacques’ original and my translation. The first was