What was known of Captain Hagberd in the little seaport of Colebrook was not exactly in his favour.

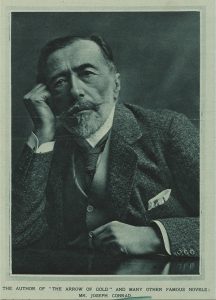

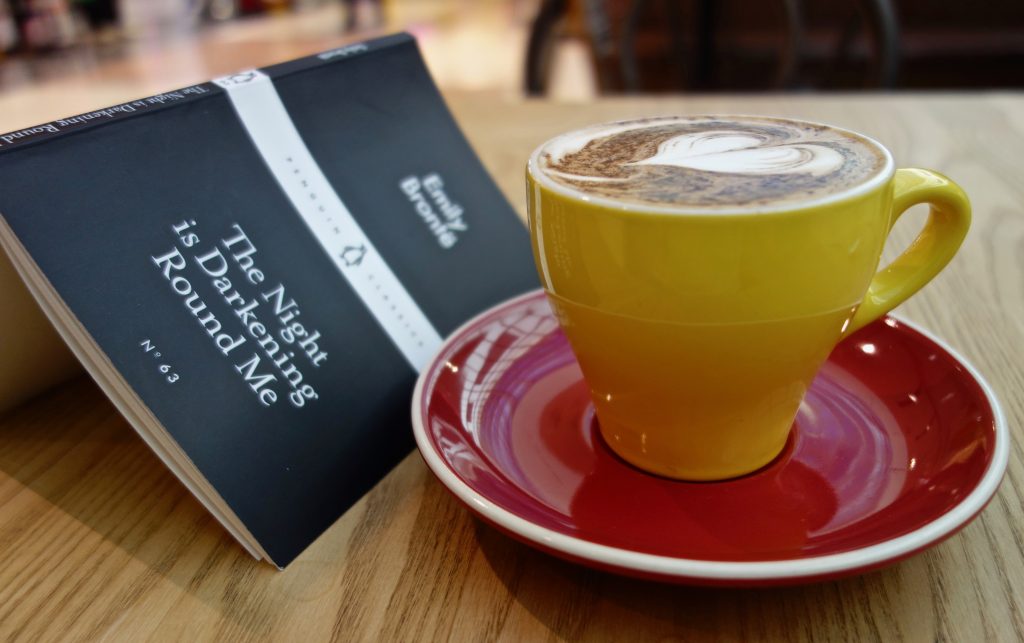

First line of To-morrow, Joseph Conrad, 1902

The story of a man who is quietly going mad waiting for his son to return, convinced he will turn up tomorrow, has an opening line promising an unsavoury old English sea captain whose ship had never gone far from home.

Reading this little book I learnt a few things about writing well, surprising really, since Conrad was born in Ukraine, was educated in Poland, and learnt English as an adult. His words had me feeling a particular pity for the poor girl who lived next door to Captain Hagberd. The two of them talked over the fence each day:

“You wait till you get married, my dear,’ said her only friend, drawing closer to the fence. […]

But she only said in self-mockery, and speaking to him as though he had been sane, ‘Why, Captain Hagberd, your son may not even want to look at me.'”

To-morrow is no. 64 in the collection of little Penguin classics, but is available online at Gutenberg and is one of the freely available e-books produced by the University of Adelaide.

*

*

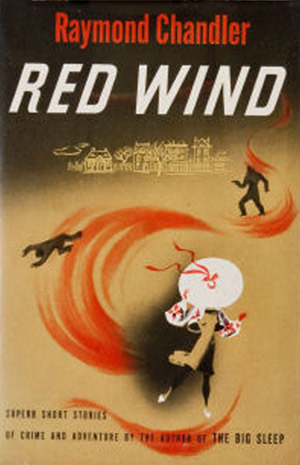

Thanks Dennis for introducing me to Philip Marlowe. I liked his references to the hot wind through the narration. ‘Outside the wind howled’; ‘… he looked cool as well as under a tension of some sort. I guessed it was the hot wind.’; ‘The wind was making enough noise to make the hard quick rap of .22 ammunition sound like a slammed door…’; ‘The wind was still blowing, oven-hot, swirling dust and torn paper up against the walls.’

Thanks Dennis for introducing me to Philip Marlowe. I liked his references to the hot wind through the narration. ‘Outside the wind howled’; ‘… he looked cool as well as under a tension of some sort. I guessed it was the hot wind.’; ‘The wind was making enough noise to make the hard quick rap of .22 ammunition sound like a slammed door…’; ‘The wind was still blowing, oven-hot, swirling dust and torn paper up against the walls.’