Today I can say, at last, that my translation, ‘The Wolf’, by Marcel Aymé, has been published by Delos Journal at the University of Florida.

I came across the original story, ‘Le Loup’, one lunchtime as I was eating my sandwich in the sun. It’s rare for a story to keep me reading all the way to the end in one sitting, but ‘Le Loup’ did it for me. When I’d finished the story, and my lunch, I began translating it immediately.

That was a couple of years ago. Publication of the piece has been a long time coming. In the world of literary translation and publishing (or any writing and publishing really), progress is often at snail pace and this is a good example.

First there was the enquiry to the French publisher, Gallimard, to see if the rights to publish a translation were available.

Months passed without a response, but prompting them brought a yes.

Second, there was the submission to journals. Many journals said No. But Delos said Yes! That was two yeses!

Then it was back to the French, who in turn had to put the question to the rights holder of Marcel Aymé’s estate. It was the beginning of a looooong negotiation process to buy the rights. Three months I waited, anxious that the journal might give up. There was no response.

But the journal editor, bless her, offered to write to the French publisher on my behalf. And I suppose it’s not surprising that she was answered tout de suite…

Weeks passed again while we waited for a response from the rights holders. Finally they quoted a price so high that I was sure my translation would really never see the light of day.

Now, in the world of literature there are people who care, good people, and one of them came to my rescue with some of the funds, but it wasn’t enough. I scraped together a bit more, and made an offer to the French. And waited. Again. The journal deadline came and went, I had no response to my (low) offer, and Delos and I agreed to drop the whole project.

Then, that very night, there was a miracle. The rights owners accepted my figure, and it was full steam ahead for ‘The Wolf’.

The editor offered to find an illustrator for the story, and with my childlike adoration of illustrations, it was a bonus thrill for me. Most French editions are illustrated with sweet images like this one showing three good friends hugging, laughing and trusting one another:

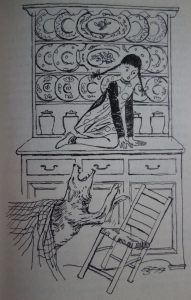

And in a past translation of ‘Le Loup’, there was even an illustration of an incident which never occurred in the story. The translator had partly tweaked the narrative to protect little readers from the truth that wolves are carnivores. In reality, the wolf didn’t miss out, he got lucky, and the girl was not dark-haired but blonde, because wolves prefer blondes:

But for the Delos issue, the editor’s daughter drew a terrifying image in pen and ink of the wolf chasing two small girls, which now accompanies my new translation. I can’t show you; it’s in the journal which is behind a paywall. But I read some pieces from archived issues when the journal was free, and can recommend it. The table of contents for the latest issue is here.

The next translation to be published will be a whole book of stories from the Belle Époque, currently being prepared for publication by Odyssey Books. Again, it’s taking a long long long time. Early next year I expect it to come out. I’ll keep you posted.

*