At the beginning of this year I took up a reading challenge set by the ACT library. The challenge was to read through the list below by the end of 2019. Here are the books I read, all but one finished.

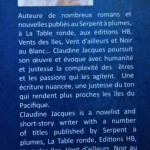

A genre you’ve never read before: Coeurs barbelés by Claudine Jacques (fiction based on the modern history of New Caledonia, currently translating it)

Something that makes you laugh: La Baleine de Jonas by Claude Aveline (humorous twist on the story of Jonah and the whale, in French)

Has a one-word title: Castaway by Robert Macklin (a new version of a true story. Yes the truth can have many versions.)

Features time travel or time slip: Maya by Jostein Gaarder (not bad, but a good translation)

Written under a pseudonym: Oliver Twist by Charles Dickens (took me 52 years to read this after first seeing the film)

That celebrates diversity: The Adventurous Princess and Other Feminist Fairy Tales by Erin-Claire Barrow (lovely book of fairy tales by my illustrator)

Set in an imaginary or alternate world: Esme’s Wish by Elizabeth Foster (good book, first of three so I don’t know how the story ends)

Crime (non-)fiction: The Tatooist of Auschwitz by Heather Morris (incredible story stumbled upon by the author. I added the -non to fiction here.)

Features food: The Land Before Avocado by Richard Glover (very good nostalgic review of Australian ways in the 60s and 70s)

Something you can read in a day: The Golden Cockerel by Alexander Pushkin (beautifully illustrated Russian story)

Has a green cover: Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame (totally excellent book my father gave me as a child but which I never read till now)

An eBook or eAudiobook: The Birth of Bran by James Stephens (a funny Irish tale illustrated by Arthur Rackham)

Set in Africa : Tea Time for the Traditionally Built by Alexander McCall Smith (one of a collection about the No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency set in Botswana)

A gothic story: Princesse d’Italie by Jean Lorrain (dark story about a Salomé play, in French)

Something you want to re-read: The Woodlanders by Thomas Hardy (great story set in 19th-century Dorset)

Something you regret not having read yet: The Magic Pudding by Norman Lindsay (I don’t regret it any more)

Recommended by family or friend: All Quiet on the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque (I know now why it was recommended)

From/about antiquity (before Middle Ages): Trimalchio’s Feast by Petronius (decadent decadence, couldn’t finish it…)

Epistolary (letter or diary format): It was snowing butterflies by Charles Darwin (not bad but not my thing)

Recommended by [pop-up] library staff: Ripening Seed by Colette (excellent descriptions but surprisingly for a female author the boy has more fun)

*

There are many more books I’ve read this year in categories not included in the ACT Library challenge. My favourite this year, not mentioned above, was A Fortunate Life by A. B. Facey.

Albert Facey reaffirmed my own fortunate life. Not fortunate in the fortune sense, but in the blessed sense.

*

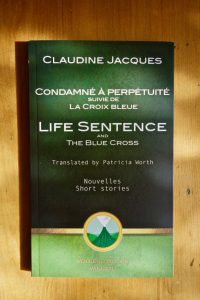

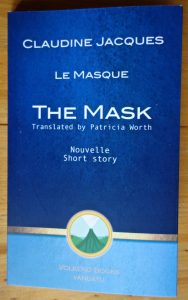

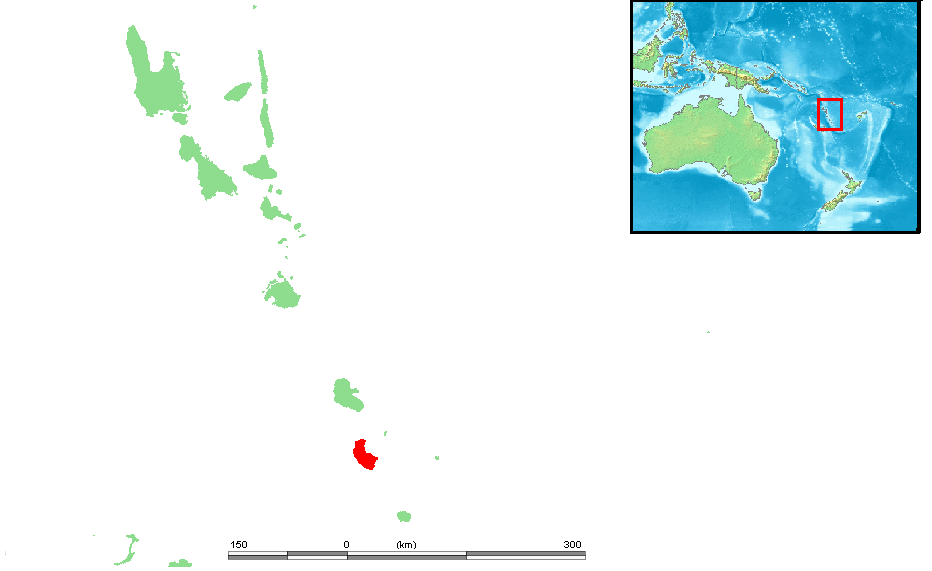

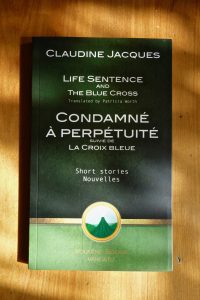

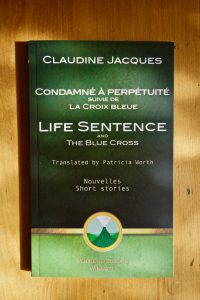

Life Sentence was published last year in Southerly Journal (Sydney University), and now it’s available in this little edition from Volkeno Books, Vanuatu. This is the second bilingual book published by Volkeno that includes Jacques’ original and my translation. The first was

Life Sentence was published last year in Southerly Journal (Sydney University), and now it’s available in this little edition from Volkeno Books, Vanuatu. This is the second bilingual book published by Volkeno that includes Jacques’ original and my translation. The first was