I had never seen so many white coats in my little room.

Opening line of The Diving Bell and the Butterfly by Jean-Dominique Bauby, translated by Jeremy Leggatt

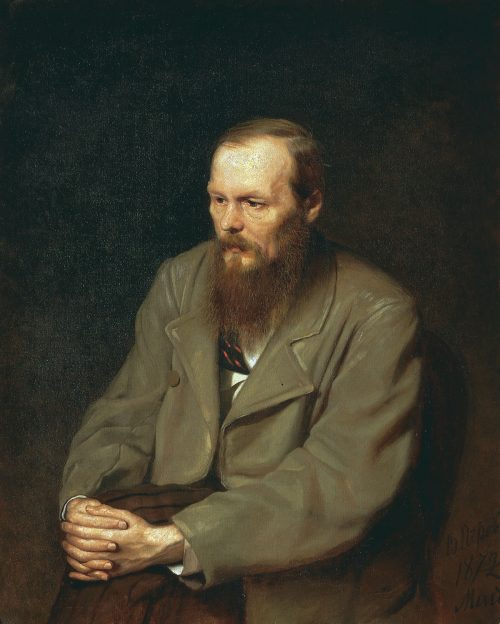

When Jean-Dominique Bauby wakes from a coma after a stroke, he’s surrounded by medical staff. He can’t move much of his body, just his head and one eye. By blinking it, he communicates with a speech therapist and dictates this book.

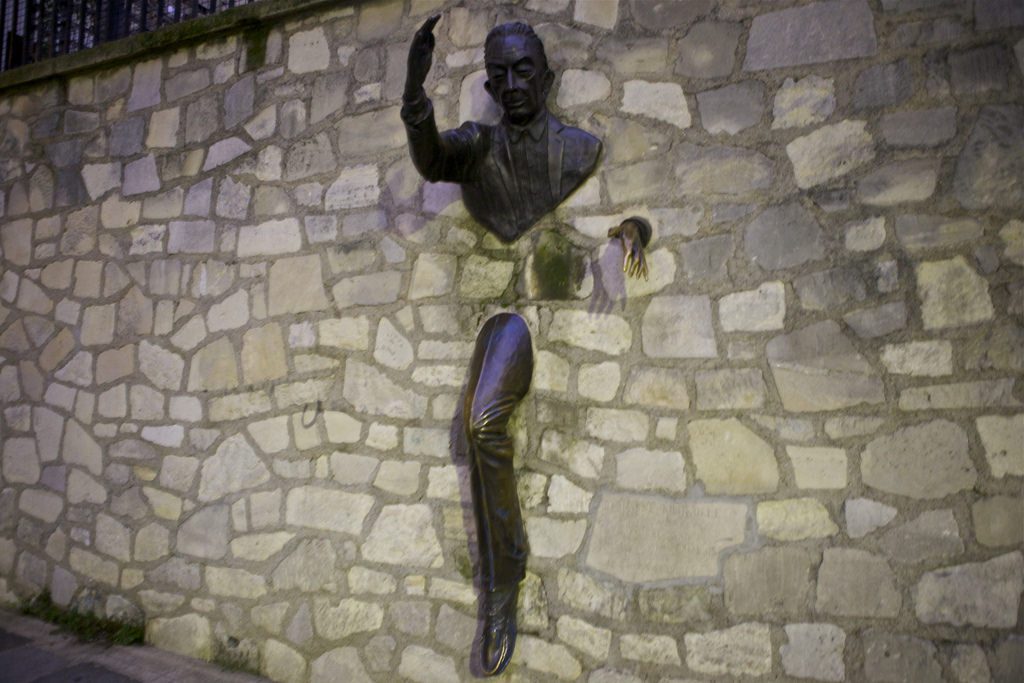

The diving bell represents his body confined and greatly restricted with Locked-in Syndrome. The butterfly is his mind taking flight, as it used to before the stroke when he was the chief editor of Elle, a French fashion magazine.

The Diving Bell and the Butterfly is amazing. Short and elegant, both the original and the translation. Highly recommended.

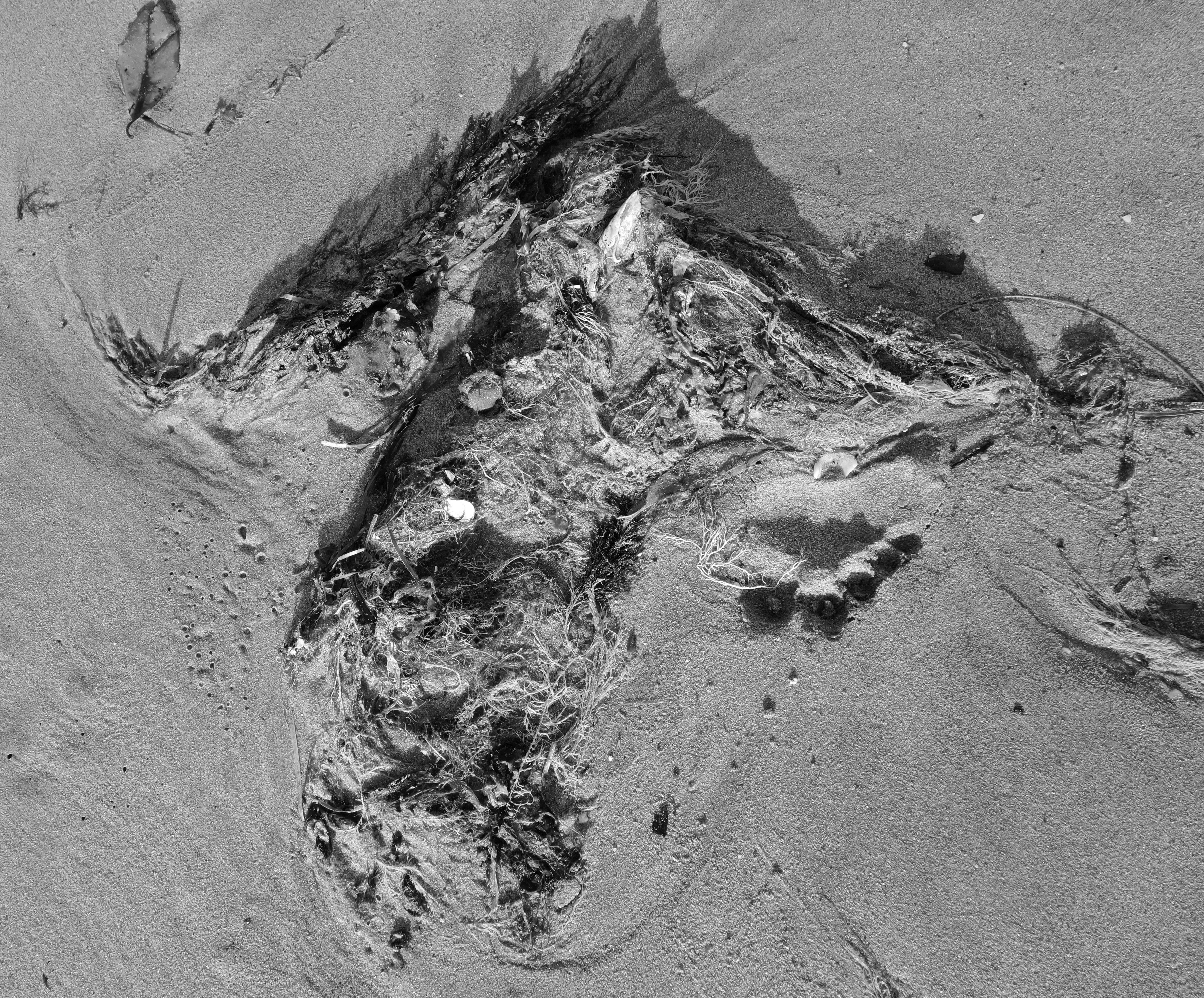

I thought about butterfly freedom this morning when I came across these two embracing beauties clinging to the fig branch in my garden. You see? Sometimes even a butterfly can be confined and restricted.

*