It’s because of the advent of digitised records – birth, death, marriage and war service records – and family tree web sites, particularly Ancestry, that I know now what I didn’t know a short time ago. I’d heard about my father’s time in Egypt as a WW2 soldier and I’d heard about his own father’s time in France as a WW1 soldier.

But I’d never heard of the family members who were killed in action.

My grandmother had two cousins, the Burley brothers, James and Frederick, who were killed in Northern France.

Can you imagine losing two sons who voluntarily went to war?

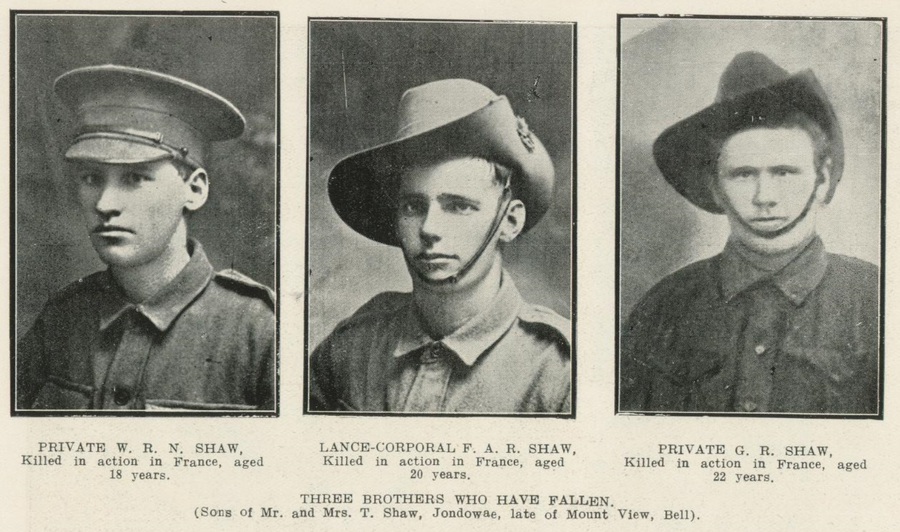

Now imagine losing three sons.

My grandfather had three cousins, the Shaw brothers, George, D’arcey and Frank, who were also killed in Northern France.

But because their cousin, my grandfather Ernest Bruce, survived gassing and a concrete wall falling on top of him, he returned to Australia to produce my father, who in turn produced me.

I’ve discovered most of this information through online records and family history websites. Many many family historians are using these resources now. This means that the great numbers of people commemorating the centenary of the armistice today, 11th November 2018, have learnt, like me, that they are the descendants of the ones who returned.

I have three sons. I feel absolute anguish for the parents who lost two or three of their children in war.

And I now have a greater appreciation of the struggles of Australians trying to build our nation a hundred years ago when the total population was 5 million, and 62,000 of their young people had been killed, and 156,000 were wounded, and many like my grandfather were unable to work again.

This building in the photo below, the Australian War Memorial, is ten minutes from my home. I’ve visited it countless times, and in the past few weeks as the crocheted and knitted poppies were displayed, and as I’ve read and heard so many stories from descendants of soldiers like me, I realise how fortunate I am that I have a comfortable home, enough food to keep me healthy, and a family that is gainfully employed. And I realise that WW1 was not the war to end all wars, there have been many wars since then, and I must not take my fortune for granted.

This new knowledge is greatly due to the digitisation of historical records, a technology I’m very grateful for.

*