At the beginning of this year I took up a reading challenge set by the ACT library. The challenge was to read through the list below by the end of 2019. Here are the books I read, all but one finished.

A genre you’ve never read before: Coeurs barbelés by Claudine Jacques (fiction based on the modern history of New Caledonia, currently translating it)

Something that makes you laugh: La Baleine de Jonas by Claude Aveline (humorous twist on the story of Jonah and the whale, in French)

Has a one-word title: Castaway by Robert Macklin (a new version of a true story. Yes the truth can have many versions.)

Features time travel or time slip: Maya by Jostein Gaarder (not bad, but a good translation)

Written under a pseudonym: Oliver Twist by Charles Dickens (took me 52 years to read this after first seeing the film)

That celebrates diversity: The Adventurous Princess and Other Feminist Fairy Tales by Erin-Claire Barrow (lovely book of fairy tales by my illustrator)

Set in an imaginary or alternate world: Esme’s Wish by Elizabeth Foster (good book, first of three so I don’t know how the story ends)

Crime (non-)fiction: The Tatooist of Auschwitz by Heather Morris (incredible story stumbled upon by the author. I added the -non to fiction here.)

Features food: The Land Before Avocado by Richard Glover (very good nostalgic review of Australian ways in the 60s and 70s)

Something you can read in a day: The Golden Cockerel by Alexander Pushkin (beautifully illustrated Russian story)

Has a green cover: Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame (totally excellent book my father gave me as a child but which I never read till now)

An eBook or eAudiobook: The Birth of Bran by James Stephens (a funny Irish tale illustrated by Arthur Rackham)

Set in Africa : Tea Time for the Traditionally Built by Alexander McCall Smith (one of a collection about the No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency set in Botswana)

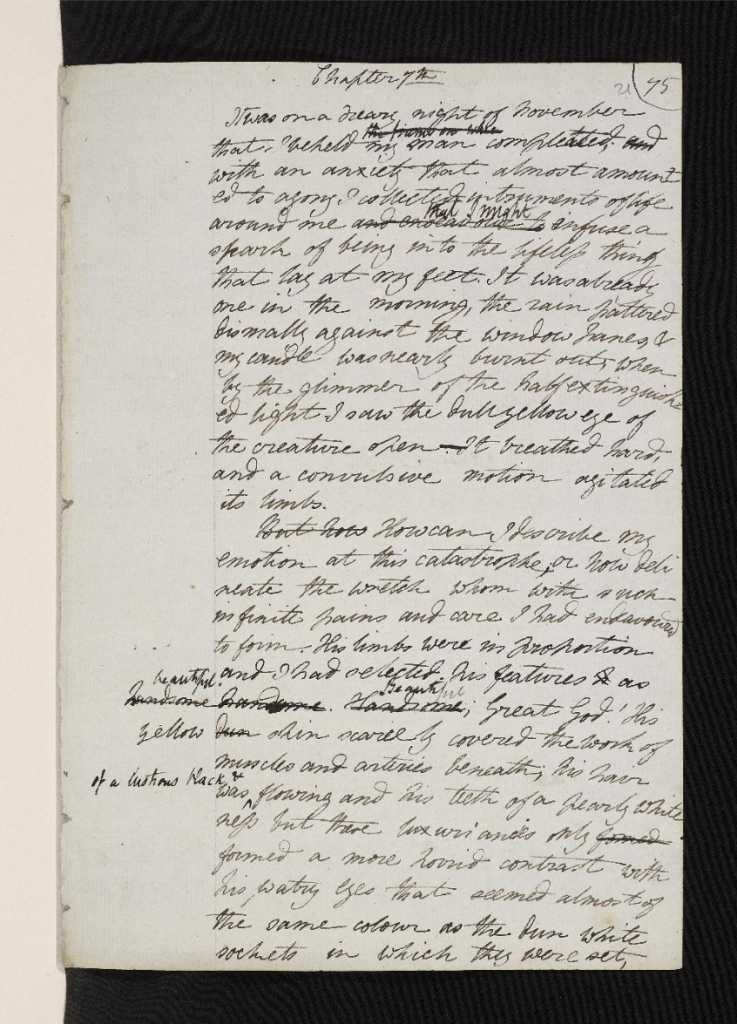

A gothic story: Princesse d’Italie by Jean Lorrain (dark story about a Salomé play, in French)

Something you want to re-read: The Woodlanders by Thomas Hardy (great story set in 19th-century Dorset)

Something you regret not having read yet: The Magic Pudding by Norman Lindsay (I don’t regret it any more)

Recommended by family or friend: All Quiet on the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque (I know now why it was recommended)

From/about antiquity (before Middle Ages): Trimalchio’s Feast by Petronius (decadent decadence, couldn’t finish it…)

Epistolary (letter or diary format): It was snowing butterflies by Charles Darwin (not bad but not my thing)

Recommended by [pop-up] library staff: Ripening Seed by Colette (excellent descriptions but surprisingly for a female author the boy has more fun)

*

There are many more books I’ve read this year in categories not included in the ACT Library challenge. My favourite this year, not mentioned above, was A Fortunate Life by A. B. Facey.

Albert Facey reaffirmed my own fortunate life. Not fortunate in the fortune sense, but in the blessed sense.

*

I recommend the film as well. The actress, Jessica Chastain, like the woman she plays, has an awesome affinity with animals that’s delightful to watch.

I recommend the film as well. The actress, Jessica Chastain, like the woman she plays, has an awesome affinity with animals that’s delightful to watch.