When the Australian government, among others, announced this week they’re sending troops off to Iraq to fight (if only in the skies for now), I thought Here we go again. As I rode past this bin today, the sign “General Waste” reminded me of the futility of war. It might seem an obscure connection, but when you see the page from my father’s anthology of war poetry compiled in about 1942, you’ll think what I thought. First, the bin:

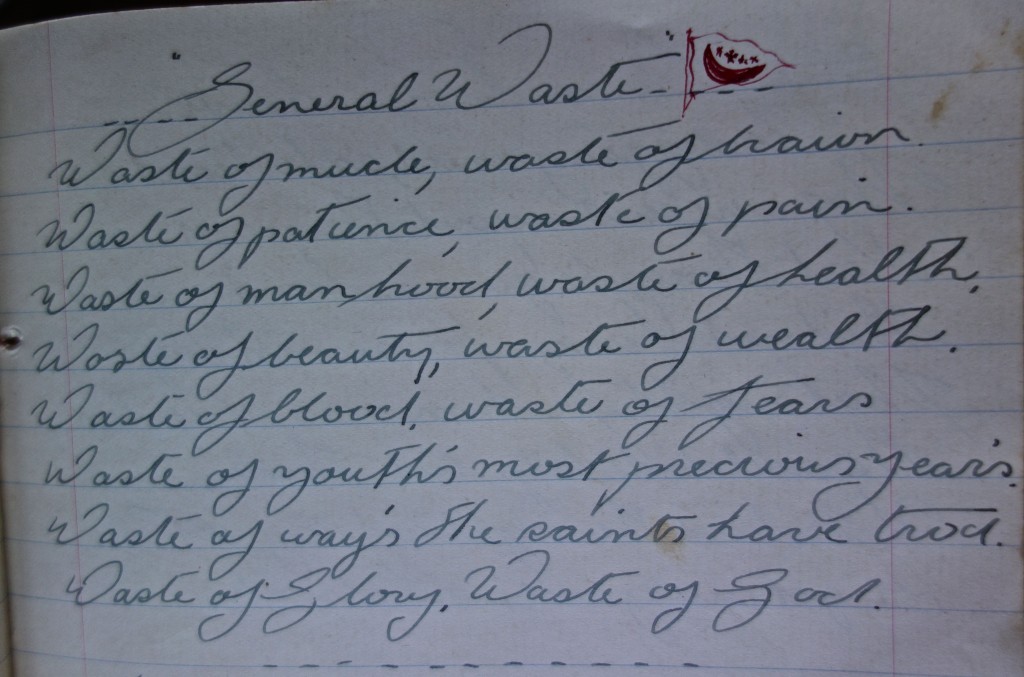

Second, a poem entitled “General Waste”, originally written in World War One by Reverend Geoffrey Studdert Kennedy, who volunteered as a British chaplain to the army on the western front. He was also known as Woodbine Willie for the Woodbines he smoked and handed out to the wounded and dying. But he had a threefold reputation, for he was also a great anti-war poet.

In Dad’s poetry book, I’ve often read “General Waste” and felt the hollowness of war. Studdert Kennedy wrote it in about 1917, but his poems were recalled by soldiers fighting again in World War Two. Dad has called it “General Waste”, though searches online suggest it was called simply “Waste”. There are a few spelling errors in his script, so I’ve transcribed it:

Waste of muscle, waste of brain,

Waste of patience, waste of pain.

Waste of manhood, waste of health,

Waste of beauty, waste of wealth.

Waste of blood, waste of tears,

Waste of youth’s most precious years.

Waste of ways the saints have trod,

Waste of Glory, Waste of God.

War!

Thanks WordPress for this week’s photo challenge.

In the foyer there are great glass windows looking onto the lake, and an artsy window dressing which produces the best shadows.

In the foyer there are great glass windows looking onto the lake, and an artsy window dressing which produces the best shadows.  As I moved up into the galleries, Eternity caught my eye. Arthur Stace famously wrote this single word in beautiful copperplate writing on the footpaths of Sydney between 1932 and 1967.

As I moved up into the galleries, Eternity caught my eye. Arthur Stace famously wrote this single word in beautiful copperplate writing on the footpaths of Sydney between 1932 and 1967.  Stace described an experience in church which prompted him to write Eternity half a million times over 35 years:

Stace described an experience in church which prompted him to write Eternity half a million times over 35 years:

One of the saddest sights in the museum was this gate, a reminder of times when some children were raised by institutions:

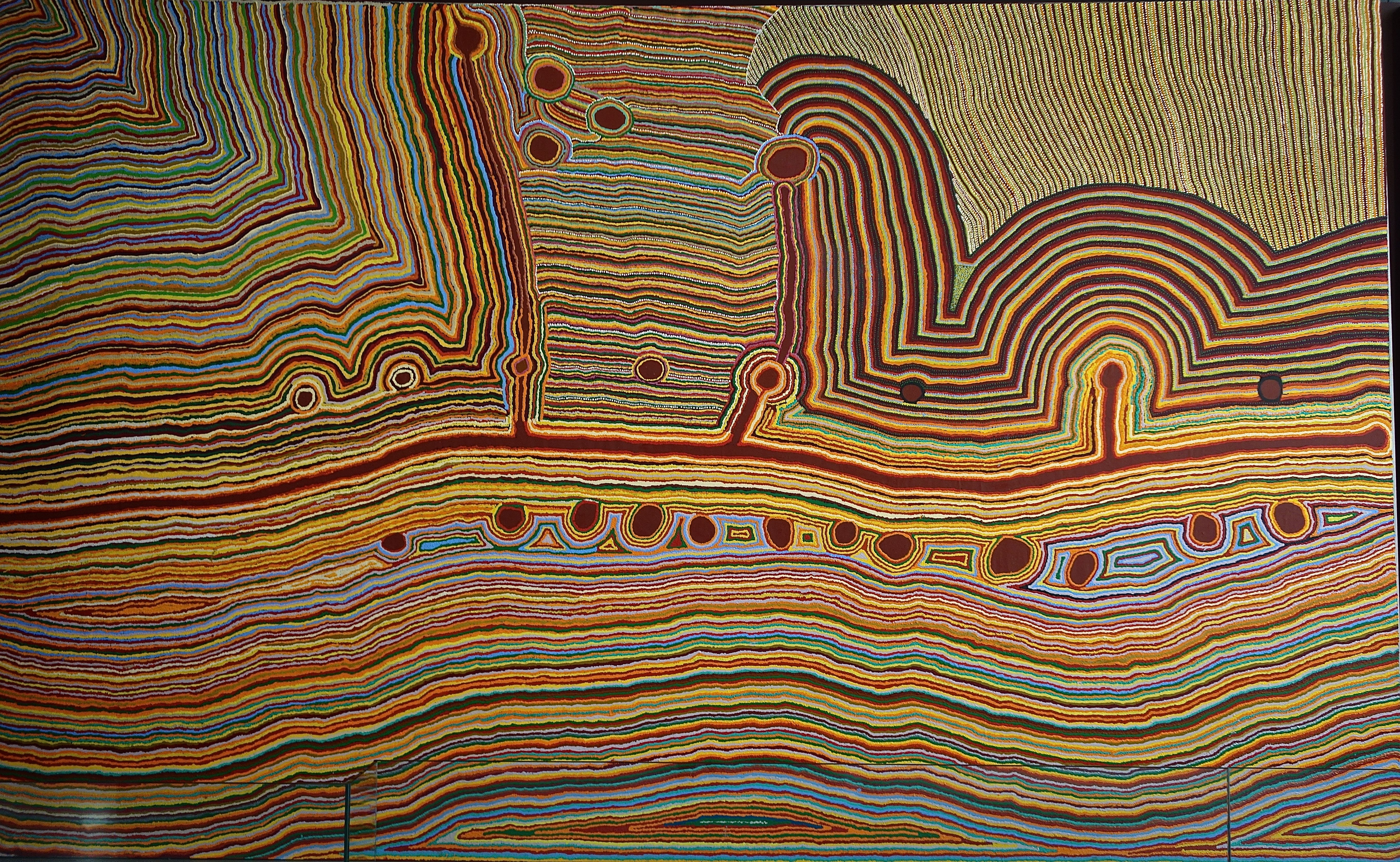

One of the saddest sights in the museum was this gate, a reminder of times when some children were raised by institutions:  There were other objects like leg irons and old pistols that remind us of our darker colonial past: and a convict bi-colour ‘magpie’ uniform, designed to deter convicts from escaping. But imagine the situation if, in 1788 and later, the roles had been reversed, and it wasn’t the English arriving to claim this land for the crown, but the Aboriginals arriving to take the land from the whites. Gordon Syron, an indigenous artist painted that ‘what if’ scene in The Black Bastards are Coming, 2006:

There were other objects like leg irons and old pistols that remind us of our darker colonial past: and a convict bi-colour ‘magpie’ uniform, designed to deter convicts from escaping. But imagine the situation if, in 1788 and later, the roles had been reversed, and it wasn’t the English arriving to claim this land for the crown, but the Aboriginals arriving to take the land from the whites. Gordon Syron, an indigenous artist painted that ‘what if’ scene in The Black Bastards are Coming, 2006:  Out on the museum terrace, one of the best spots to get a quiet waterside coffee, I was contemplating eternity when a man and dog came past on a surfboard (lakeboard?).

Out on the museum terrace, one of the best spots to get a quiet waterside coffee, I was contemplating eternity when a man and dog came past on a surfboard (lakeboard?).