Time-filling. And people watching. That’s what this is.

In Bluey’s café none of us has red hair.

Here’s to Mondays.

*

A quiet place.

I stumbled on a reading challenge by my local ACT library this week, and at first I dismissed it as I do with challenges generally. But the list of categories looked manageable for what remains of 2019 and the thought occurred to me that I could tick them off, no worries. It came to me a few days after I found a new library in the small Australian Catholic University around the corner from me that has a very welcoming wall at the entrance. Here it is. Zoom in (click and click again) to read students’ stick-it notes…

Here I picked up a book I’d always avoided for no good reason, The Magic Pudding by Norman Lindsay, an early Australian classic, which fits one of the categories of the challenge, ‘Something you regret not having read yet’.

And then this morning, I cast my eye quickly over the pop-up library outside a local café. Zoom in to see what sort of books Canberrans read…

There on the shelf was a book that someone once highly recommended, The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini. I’ve brought it home, except now I remember having read it, but it fits another challenge category, ‘Something you want to re-read’.

That’s two. But I have a third book that fits the category ‘Set in an imaginary world’: Contes féeriques (Faeric Tales) by Théodore de Banville. The title page is illustrated by Georges Rochegrosse, his stepson. Note the age spots, it’s an old one. Zoom in to see the fairies floating around the amorous couple…

Banville wittily gives it the subtitle ‘Scenes from Life’, but every tale revolves around the intervention of a fairy, magician or other supernatural figure! I recently had a translated story published that comes from this collection, ‘The Lydian’ which you can read for free if you click the link, and if you click here you can read more about it. But I haven’t yet read every story in the book, so it’s going on my challenge list.

That’s three, and only seventeen more to find to tick off everything on the challenge list. It should take my reading to the end of this year:

2019 Libraries ACT Reading Challenge

*

It’s presently the fourth day of 40+ degrees celsius outside and 30+ in my house and I’m too weary to translate stories, a task that requires a cool unflustered mind. But I can show you what it’s like at my place in this heatwave where even the birds and bees are too hot to fly…

As the temperature climbed this afternoon, I started to melt, and turned the fan on without a thought for the consequences. I might as well have cast my neatly stacked, unbound manuscript to the wind…

Too hot and bothered to face this papery mess, I retreated to the kitchen to find something cold. The fridge is a friend on days like these, and as I opened its door, the freezer offered up a consoling box of Weis bars that I’d bought to take me back to my Queensland childhood.

While the disorderly manuscript was waiting on the floor for me to cool down, the ever-turning fan blew even more pages down onto the pile. I picked it all up and dumped it on the lounge, to deal with in the cool of the evening (which this week has been about 3am). Fortunately the pages are numbered, a trick I once learnt after dropping a longish story, its pages loose and unnumbered.

It’s now 7.30, the light is failing, it’s 30 degrees out and 30 in. My house holds its heat, a desirable eco feature in winter but not in a summer heatwave. An hour ago the sky clouded over, and out of it some pathetic rain drops fell for a few minutes and stopped.

Sigh.

*

The 11th of the 11th is not far off. The Australian War Memorial here in Canberra is demonstrating the community’s sorrow over all those who died in World War 1, the war to end all wars. Not. Crocheted and knitted poppies have been planted in the lawn, 62,000 of them, one for each of the dead, forming a sea of red spilling out in front of our beautiful war memorial building.

Poppy posts and photos are appearing all around the country. I’ve read that 62,000 poppies was the goal for the project, but the women (mostly women) contributed many many more. The extras have been used in a display in Parliament House and in towns around Australia. I made 12, and I taught my Japanese student to crochet and then she made 12. Our 24 poppies are there in the crowd somewhere.

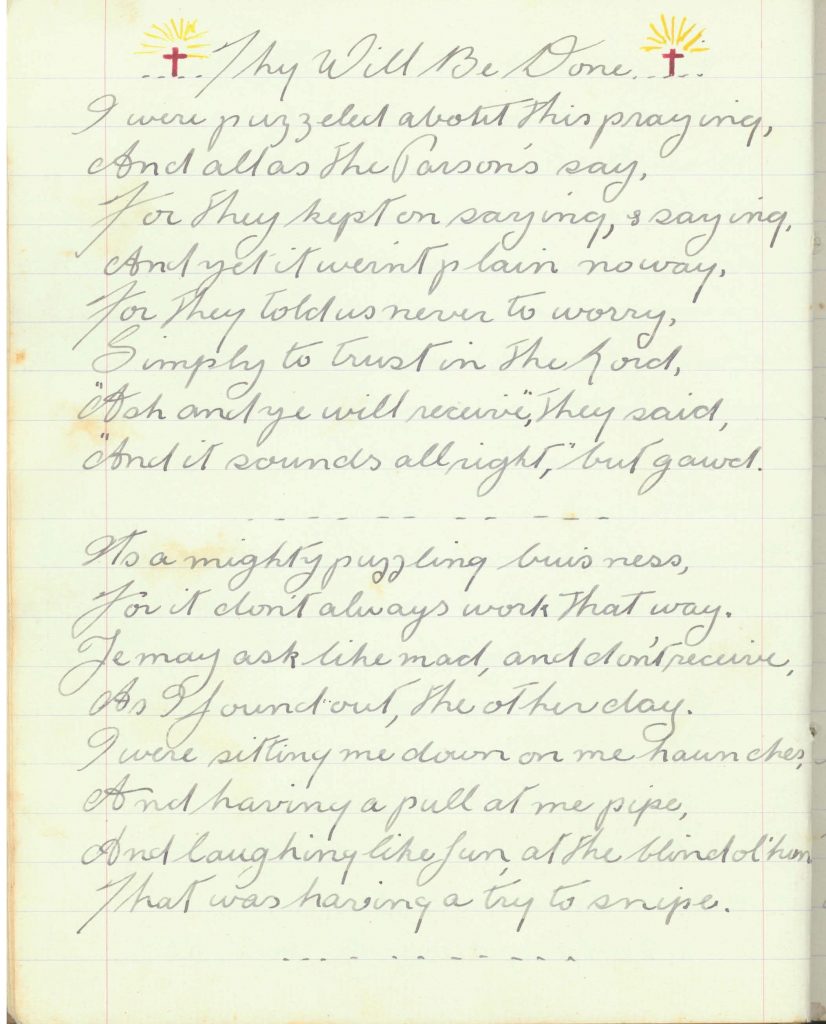

All this talk about the centenary of the armistice reminded me of a poem I read in my father’s poetry book that he brought back from World War 2. He recorded poems he wanted to remember, and re-reading this one leaves me wondering what it meant to him, especially the final verse. The poet was Rev. G. A. Studdert Kennedy who allowed it to be circulated among the soldiers. It speaks of a death by gassing and may have comforted some of those who had lost mates to this horrific weapon. My father’s father was gassed in 1916, but survived. Perhaps Dad had him in mind when he recorded this poem in 1942. Here’s his first page:

Reverend Geoffrey Studdert Kennedy was a volunteer British chaplain to the army on the western front, and was also known as Woodbine Willie for the Woodbines he smoked and handed out to the wounded and dying. He was a great anti-war poet.

Here’s the whole poem written in 1917 in soldier-dialect :

Thy Will Be Done

A Sermon in a Hospital

by Rev. G. A. Studdert Kennedy, from Rough Rhymes of a Padre, 1918

I WERE puzzled about this prayin’ stunt,

And all as the parsons say,

For they kep’ on sayin’, and sayin’,

And yet it weren’t plain no way.

For they told us never to worry,

But simply to trust in the Lord,

“Ask and ye shall receive,” they said,

And it sounds orlright, but, Gawd!

It’s a mighty puzzling business,

For it don’t allus work that way,

Ye may ask like mad, and ye don’t receive.

As I found out t’other day.

I were sittin’ me down on my ‘unkers,

And ‘avin’ a pull at my pipe,

And larfin’ like fun at a blind old ‘Un,

What were ‘avin’ a try to snipe.

For ‘e couldn’t shoot for monkey nuts,

The blinkin’ blear-eyed ass,

So I sits, and I spits, and I ‘ums a tune;

And I never thought o’ the gas.

Then all of a suddint I jumps to my feet,

For I ‘eard the strombos sound,

And I pops up my ‘ead a bit over the bags

To ‘ave a good look all round.

And there I seed it, comin’ across,

Like a girt big yaller cloud,

Then I ‘olds my breath, i’ the fear o’ death,

Till I bust, then I prayed aloud.

I prayed to the Lord Almighty above,

For to shift that blinkin’ wind,

But it kep’ on blowin’ the same old way,

And the chap next me, ‘e grinned.

“It’s no use prayin’,” ‘e said, “let’s run,”

And we fairly took to our ‘eels,

But the gas ran faster nor we could run,

And, Gawd, you know ‘ow it feels

Like a thousand rats and a million chats,

All tearin’ away at your chest,

And your legs won’t run, and you’re fairly done,

And you’ve got to give up and rest.

Then the darkness comes, and ye knows no more

Till ye wakes in an ‘orspital bed.

And some never knows nothin’ more at all,

Like my pal Bill–‘e’s dead.

Now, ‘ow was it ‘E didn’t shift that wind,

When I axed in the name o’ the Lord?

With the ‘orror of death in every breath,

Still I prayed every breath I drawed.

That beat me clean, and I thought and I thought

Till I came near bustin’ my ‘ead.

It weren’t for me I were grieved, ye see,

It were my pal Bill–‘e’s dead.

For me, I’m a single man, but Bill

‘As kiddies at ‘ome and a wife.

And why ever the Lord didn’t shift that wind

I just couldn’t see for my life.

But I’ve just bin readin’ a story ‘ere,

Of the night afore Jesus died,

And of ‘ow ‘E prayed in Gethsemane,

‘Ow ‘E fell on ‘Is face and cried.

Cried to the Lord Almighty above

Till ‘E broke in a bloody sweat,

And ‘E were the Son of the Lord, ‘E were,

And ‘E prayed to ‘Im ‘ard; and yet,

And yet ‘E ‘ad to go through wiv it, boys,

Just same as pore Bill what died.

‘E prayed to the Lord, and ‘E sweated blood,

And yet ‘E were crucified.

But ‘Is prayer were answered, I sees it now,

For though ‘E were sorely tried,

Still ‘E went wiv ‘Is trust in the Lord unbroke,

And ‘Is soul it were satisfied.

For ‘E felt ‘E were doin’ God’s Will, ye see,

What ‘E came on the earth to do,

And the answer what came to the prayers ‘E prayed

Were ‘Is power to see it through;

To see it through to the bitter end,

And to die like a Gawd at the last,

In a glory of light that were dawning bright

Wi’ the sorrow of death all past.

And the Christ who was ‘ung on the Cross is Gawd,

True Gawd for me and you,

For the only Gawd that a true man trusts

Is the Gawd what sees it through.

And Bill, ‘e were doin’ ‘is duty, boys,

What ‘e came on the earth to do,

And the answer what came to the prayers I prayed

Were ‘is power to see it through;

To see it through to the very end,

And to die as my old pal died,

Wi’ a thought for ‘is pal and a prayer for ‘is gal,

And ‘is brave ‘eart satisfied.

*

Apparently, it’s good for writers to write reviews of other writers’ work. I’ve never done it and never wanted to, till now.

I had a great morning walking round some natural ponds and listening to hundreds of frogs croaking among reeds, all thanks to one small book: Walking Canberra by Graeme Barrow, self-published in 2014. So I feel compelled to share this pleasure with anyone who might be contemplating a walk in our beautiful bush capital. Here goes my first book review…

Waiting to be served at my local newsagent, my eyes fell on this little book propped up among the sweets at the counter. The full title held my attention: Walking Canberra: 101 ways to see Australia’s national capital on foot. I’d long been considering how to get some exercise and at the same time discover some of the unknown treasures and pleasures in our world, and this title promised to deliver exactly that.

Walking Canberra is nothing like the stuff I work on as a translator, it’s neither a fairy tale nor a New Caledonian drama, yet it’s currently a favourite book that I’ve been referring to for the past four weeks. I’ve heard there aren’t many copies left because it’s going out of print. Graeme Barrow self-published his books through his own business, Dagraja Press. He was a Canberra journalist who wrote books on bushwalking in this region, as well as a few local histories. He died in May last year, so here’s hoping that someone else will take on the project of updating his advice on walking in Canberra’s parks and bushland as the city changes and grows and old paths and landmarks are moved or removed.

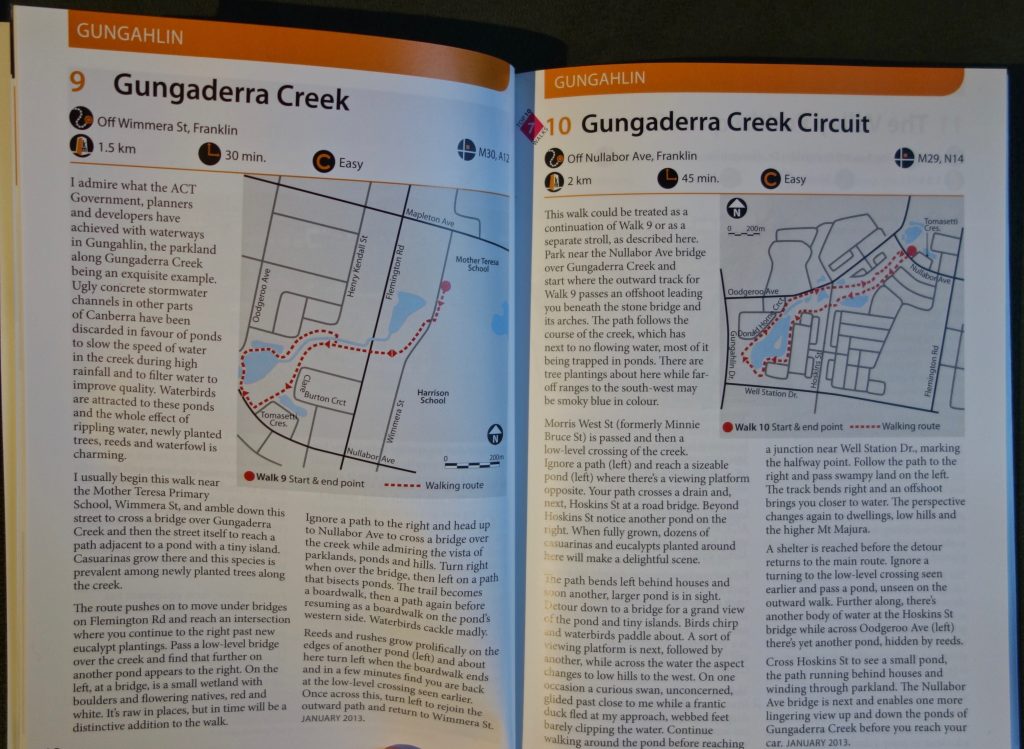

Barrow wrote like a friend to friends. The information and instructions are clear as a bell, and though he published it in 2014, I’ve found that the details (in the walks I’ve taken so far) are still correct. There are small maps on each page, and a description of what to see along the way, an outline of where to turn, where to linger and what to avoid.

Last weekend and this, my husband and I walked the Gungaderra Creek Circuit, chosen by me because of its level of difficulty: “Easy”. The local government has created a series of ponds instead of the usual concrete stormwater drains, and these ponds attract water birds and frogs frogs frogs which are invisible among the reeds but loud! There are no frogs in my suburb so this sound was a surprise.

While walking in what is essentially still suburbia, there are reminders here and there of human slips in the design: a thorny rosebush growing as though grafted onto a young eucalypt, a pink soccer ball fallen into the dense reed bed…

… and there’s the street beside Gungaderra Creek that was named and renamed after two Australian authors…

Minnie Bruce was the author Mary Grant Bruce, famous for her Billabong series, who was granted a street name in a suburb (Franklin) where Australian authors were the theme. Ten years ago her family asked for the name to be revoked since her mother was known as Minnie, and Mary was known as Mary (despite being named Minnie at birth). So, Morris West, another Australian author, was given the street. West was famous for many novels but particularly his first, The Devil’s Advocate, which has been reprinted more times than any other modern Australian novel. Now there’s a claim to fame that deserves its own street!

Out of the 101 ways to see Australia’s national capital on foot I’ve already done about 47 by dint of having lived here for 21 years. I’m thrilled to have found this special book that gives me ideas for filling my free days for the next 21 years.

*

The rabbits came many grandparents ago.

First line, The Rabbits, John Marsden, 1998

The phrase ‘many grandparents ago’ is a brilliant way of defining time for Australian descendants of immigrants. For me, it’s a great opener to an unsettling story.

The Rabbits is a fable about two things multiplying prolifically in this country: rabbits and non-Indigenous people. John Marsden is cryptically commenting on the coincidence of the human and rabbit population explosion since the arrival of the British in 1788. The illustrator Shaun Tan produced quite disturbing images for the award-winning book destined for older children but for us adults too.

This week, I read two conflicting things. I read The Rabbits with my adult student who has come here from across the seas, and explained to her the problem caused by introducing these cute fluffy creatures into Australia. And also this week I read this advertisement near my house:

Are they serious?

*

On an exceptionally hot evening early in July a young man came out of the garret in which he lodged in S. Place and walked slowly, as though in hesitation, towards K. bridge.

Opening line, Crime and Punishment, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, translated by Constance Garnett

Last night I could have written:

On an exceptionally hot evening early in January a middle-aged couple came out of the house in which they lodged in H. Street and walked slowly, as though in hesitation, towards C. bridge.

Yesterday evening and this evening are the endings of exceptionally hot days in Canberra. Today, 39 degrees.

Perhaps you didn’t imagine Dostoyevsky’s character walking towards a bridge like this one. Rather, since I don’t have any photos of Russian bridges, you might have seen him heading for a bridge resembling this old one in Cairo, where the evenings are undoubtedly hot:

I confess I haven’t read Crime and Punishment though I have read other Dostoyevsky works. But when I compared the opening line translated into English by three different translators, I thought it was worth writing about. My favourite is Constance Garnett’s 33 words in a succinct sentence, quoted above. Compare it with the 46 words of Katz’s translation:

In the beginning of July, during an extremely hot spell, toward evening, a young man left his tiny room, which he sublet from some tenants who lived in Stolyarnyi Lane, stepped out onto the street, and slowly, as if indecisively, set off towards the Kokushkin Bridge. (Translated by Michael Katz)

Plenty of detail, but I was lost after ‘sublet’. In my humble opinion there are 13 words too many. That said, I can’t read Russian and therefore can’t really say if there are omissions or additions. Now look at this one by Oliver Ready:

In early July, in exceptional heat, towards evening, a young man left the garret he was renting in S–y Lane, stepped outside, and slowly, as if in two minds, set off towards K–n Bridge. (Translated by Oliver Ready)

The number of words is similar to Garnett’s, but what it loses (for me) is the immediacy in her first words, “On an exceptionally hot evening…”. The other two translators tell us first off what month it is, but that’s not as good a beginning for a great opening line.

Perhaps I’m presently susceptible to Garnett’s first words since it’s about 10 pm and the temperature in my house is still 30 degrees.

*

Here we are at the end of the year, and here I am, writing the last of my twelve Changing Seasons posts in response to Cardinal Guzman’s photo challenge.

Canberra, December. Last week, schools finished for the year, and children began six weeks of summer holidays. In anticipation of Christmas, they’re enjoying the city’s decorations and festivities. In past years the local government has put up a huge FAKE Christmas tree in the centre of the city, which, in my humble opinion, has always been disappointing. But this year they’ve made an effort. We have a forest of trees within a forest of trees.

Children are invited to pick up a bag of decorations and dress the trees. The December sunlight filtering through the tall trees and small trees makes a pretty carpet. And the innocence of children taking pleasure in choosing their own decoration and their own tree was a perfect subject for me with my camera. Two toddlers, however, were reprimanded by their mothers for pinching a coloured ball and carrying it off… The innocence was relative, after all.

My Christmas wish for my blog readers: May you not be caught filching baubles.

Merry Christmas to all of you wonderful bloggers out there.

*

I had never seen so many white coats in my little room.

Opening line of The Diving Bell and the Butterfly by Jean-Dominique Bauby, translated by Jeremy Leggatt

When Jean-Dominique Bauby wakes from a coma after a stroke, he’s surrounded by medical staff. He can’t move much of his body, just his head and one eye. By blinking it, he communicates with a speech therapist and dictates this book.

The diving bell represents his body confined and greatly restricted with Locked-in Syndrome. The butterfly is his mind taking flight, as it used to before the stroke when he was the chief editor of Elle, a French fashion magazine.

The Diving Bell and the Butterfly is amazing. Short and elegant, both the original and the translation. Highly recommended.

I thought about butterfly freedom this morning when I came across these two embracing beauties clinging to the fig branch in my garden. You see? Sometimes even a butterfly can be confined and restricted.

*

This weekend I went to a kind of food fair, a Taste of Braddon, a suburb that some are calling the hipster suburb of Canberra. A couple of streets that not long ago were the place to go if you wanted to buy or repair a car have now been transformed into the place to eat hip food all day, drink coffee in the mornings and anything else you’d like in the evenings.

A Taste of Braddon is happening because it’s November, it’s warm, and the foodies of the inner suburbs are happy to be out in the sunshine. The ice cream limousine is sure to attract a lot of customers, even if it’s just for a look.

I would have been more tempted to buy a cone full of gelato if I’d not just finished a large cappuccino made by Ben the barista (my son) from the Lonsdale Street Roasters stall. The colourful shop-in-a-limo attracted a lot of children (not that they could have bought an ice cream without a debit card…). But isn’t it a great idea? One thing was curious: the fridge was running on a generator sitting on the grass off to the right, but how did they transport it without it all melting?

Only one more month to go in Cardinal Guzman’s seasonal photo challenge. Check out his Norwegian Oktober.

*