Have you ever gone to a place for the first time because you read about it in a story?

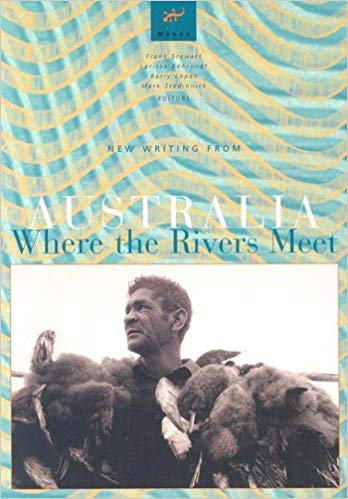

I recently read ‘On the Edge’ by an Australian writer, Ashley Hay. I came at it the long way round, beginning with ‘The Little Red Writing Book’ by Mark Tredinnick, a beautifully written, exceedingly helpful Australian book for writers who write like public servants but want to break away from that stilted language. Early in the book Tredinnick praises the writing of Barry Lopez, an American, and recommends Lopez’s writing about nature. So I went searching and saw Lopez’s name come up as an editor of ‘Where the Rivers Meet’, an Australian collection of short stories about our land, the nature of it, the history of it. ‘On the Edge’ was in it.

Ashley Hay wrote about the city of Wollongong, south of Sydney, built between the coastal mountains and the ocean and necessarily spreading north and south but never east or west. The whole city is ‘on the edge’ of Australia. She remembered being taken for a drive, as a teenager, along the road that once precariously hugged the steep cliffs prone to rockfalls, and compared it with the bridge that has replaced that road, the SeaCliff Bridge, a cantilevered serpentine bridge that follows the same coastline but in an open space over the ocean.

I tried to imagine it. I looked at the photos online, but I wanted to feel it, to see it.

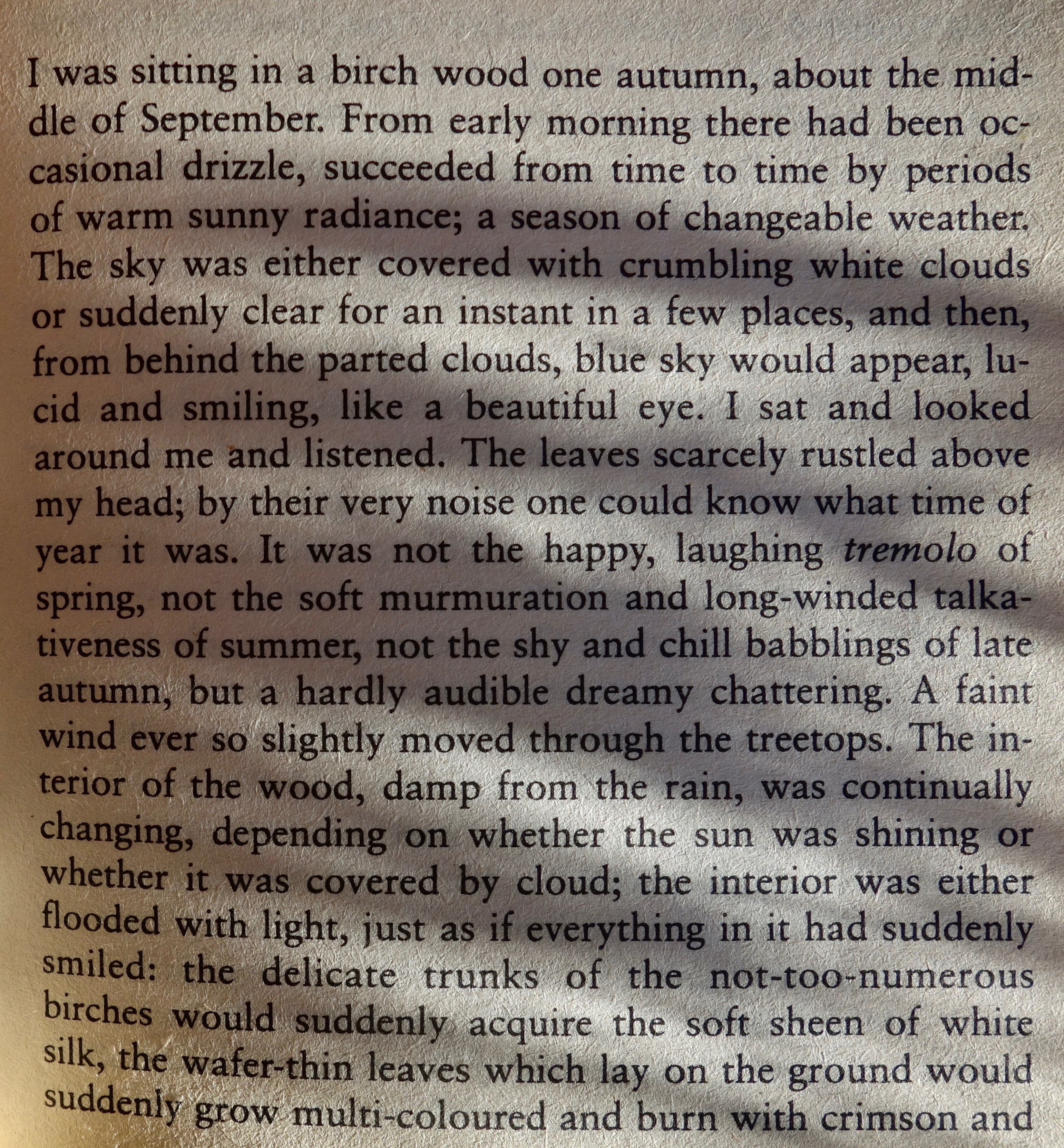

Today, I’m in Wollongong, and am being driven to the bridge. It’s pouring, a deluge of rain that began at 5am and hasn’t stopped since. We’re on the bridge, three tourists in brightly coloured raincoats are taking photos of each other joyously holding their arms out as the rain beats down. Not another soul can be seen, and barely another car. I’m not as bold as the tourists, I can’t get out and walk in this weather, so we continue along the road up to Bald Hill Lookout where the cloud is low and the wind is gusting and whoomping the car. The view is supposed to look as it does in this advertisement for the new seats by Outdoor Design :

But today the view looks like this:

The sea is invisible, can’t open the windows, no point staying. We turn back towards the bridge and search for a place to stop so I can get out, stand still, and take in the view of this bridge I have only known in a story. The car parks are some distance away but I want to see what it’s like to walk on the bridge. I’ll need to take a photo and won’t be able to hold my umbrella steady in this wind, let alone a camera. It’s too hard, I give up and take a happy snap through the windscreen of our moving car.

The view was so blurred by the torrents of rain that if I hadn’t seen photos of the SeaCliff Bridge I still wouldn’t know what it looked like. So what have I gained by wanting to get inside someone else’s story?

Perhaps tomorrow will not be a rainy day.

*