Morning, Valldemossa. Defeated by the insomnia of jet lag, I rise and open the curtains to a full moon shining on me. It’s four o’clock. Sheep down below the valley wall shuffle through grass, chewing and bleating. No other sound; no other presence; it’s the other extreme of Valldemossa. Twelve hours ago the streets crawled with tourists, Europeans on spring holiday spending their money in the restaurants and terrace cafés, in the souvenir and art shops. Their numbers surprised me. I’d expected this small village to be of minor touristic interest, but I was wrong. It’s all because of George Sand. Well, more precisely, because of Frédéric Chopin.

His is the famous name. Even the non-musical could tell you he composed music in some past century. Without him, Valldemossa’s cafés wouldn’t be nearly as profitable. It began when he fell in love with one of nineteenth-century-France’s gifted writers, George Sand, a woman six years older with two children in tow. In need of a warmer, healing clime for his bad chest, they ventured to Mallorca in the Mediterranean. After a few weeks of hurdles and blocks (inevitable when travelling abroad) they found themselves on the west coast of the island, temporary residents of three monk cells in a recently secularised monastery, the Real Cartuja de Valldemossa. Real for Royal. Cartuja for Carthusian. Once a king’s residence, then a Carthusian monastery. Now a museum and tourist attraction.

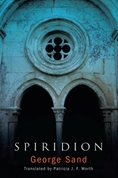

I’m quietly, very quietly, celebrating the publishing of my translation of Spiridion, George Sand’s novel that she finished in the cells of the Real Cartuja while Chopin, in his poor health, composed several pieces – Preludes, a Polonaise, a Ballade, a Scherzo.

When you wake at three, the morning is long. I wait for the new day by writing, and eating scraps of leftover food, my First Breakfast, like the hobbit. Now it’s ten to seven and the ragged Mallorcan mountains are silhouetted in the east. It’s seven o’clock and church bells in the monastery are ringing. It’s twenty past seven and there’s light, soft and shaded by mountains. The warm yellow street lamps are still on. It’s a quarter to eight and the lamps are now off. It’s half past eight and the hotel owners have set the tables. Time for Second Breakfast.

![The Collector | [John Fowles] The Collector | [John Fowles]](http://ecx.images-amazon.com/images/I/51V1elV05rL._SL300_.jpg)

![The Book of Ebenezer le Page | [G. B. Edwards] The Book of Ebenezer le Page | [G. B. Edwards]](http://ecx.images-amazon.com/images/I/51qkZldzsaL._SL300_.jpg)