The siege of Tobruk began 75 years ago on 10th April, 1941, and yesterday in Canberra the anniversary was marked at the ‘Rats of Tobruk’ memorial on Anzac Avenue.

Tobruk is a small town on the Libyan coast with a deep water harbour, which Australian, British and Indian troops were charged with protecting in 1941 to prevent Rommel and his German forces from accessing the port and advancing into Egypt. The men of the Tobruk garrison withstood attacks for eight months, never retreating or surrendering. The Nazi propagandist ‘Lord Haw Haw’ said they were like ‘rats in a trap’, and from then the Australian troops proudly called themselves the ‘Rats of Tobruk’.

My father arrived in North Africa in September and worked in the hospital where he saw numbers of wounded men from Tobruk. Other soldiers gave him some photos of the harbour and town of Tobruk in various states of ruin, which he brought back in an album when he returned to Australia. A couple of photos are enough to give an idea of the bay in 1941.

The monument on Anzac Avenue is modelled after another one which you can see in the black and white photo, constructed in the cemetery at Tobruk but destroyed a few months after. Beside it is the present monument in Canberra in a photo I took today. On the front of the new one is a bronze eternal flame that faces the avenue, below which were laid wreaths for the 75th anniversary of the siege:

The Tobruk siege is significant for two firsts. It was the first defeat of Hitler’s troops on land. And Corporal John Hurst Edmondson, who died from wounds and is buried in Tobruk cemetery (and whose grave photo is also in my father’s album) was the first Australian to be awarded the Victoria Cross in the war (awarded posthumously).

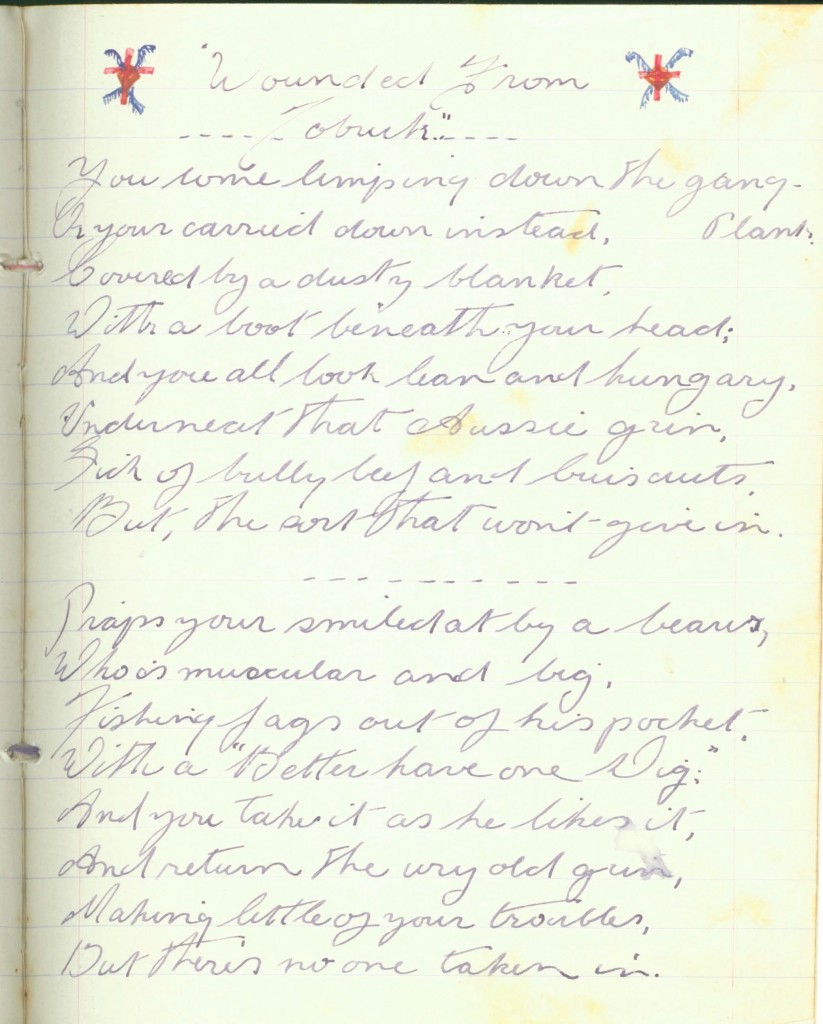

Finally, a poem. Here are the first two stanzas of Wounded from Tobruk, recorded by my father in his poetry book, but written by James Andrew “Tip” Kelaher and published in The Bulletin on 29 October 1941. Sadly, Tip Kelaher was killed the following year at El Alamein in Libya. Here’s the page in my father’s writing, followed by my transcription with corrections:

You come limping down the gangplank

Or you’re carried down instead,

Covered by a dusty blanket

With a boot beneath your head,

And you all look lean and hungry

Underneath that Aussie grin,

Sick of bully beef and biscuits,

But the sort that won’t give in.

Perhaps you’re smiled at by a bearer,

Who is muscular and big,

Fishing fags out of his pocket

With a “Better have one, Dig”.

And you take it as he lights it,

And return the wry old grin,

Making little of your troubles,

But there’s no one taken in.

Poets, photographers, artists, sculptors, and a corporal who saved a man but sacrificed his own life. We must write about them lest we forget.

*****