The 11th of the 11th is not far off. The Australian War Memorial here in Canberra is demonstrating the community’s sorrow over all those who died in World War 1, the war to end all wars. Not. Crocheted and knitted poppies have been planted in the lawn, 62,000 of them, one for each of the dead, forming a sea of red spilling out in front of our beautiful war memorial building.

Poppy posts and photos are appearing all around the country. I’ve read that 62,000 poppies was the goal for the project, but the women (mostly women) contributed many many more. The extras have been used in a display in Parliament House and in towns around Australia. I made 12, and I taught my Japanese student to crochet and then she made 12. Our 24 poppies are there in the crowd somewhere.

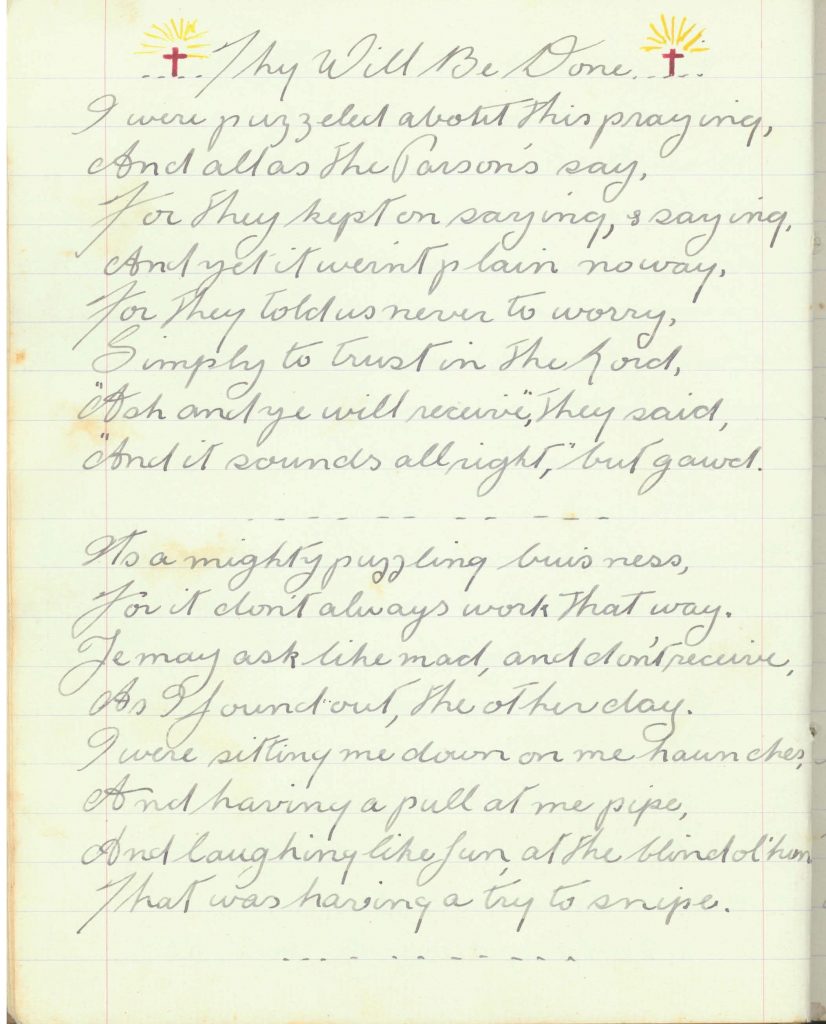

All this talk about the centenary of the armistice reminded me of a poem I read in my father’s poetry book that he brought back from World War 2. He recorded poems he wanted to remember, and re-reading this one leaves me wondering what it meant to him, especially the final verse. The poet was Rev. G. A. Studdert Kennedy who allowed it to be circulated among the soldiers. It speaks of a death by gassing and may have comforted some of those who had lost mates to this horrific weapon. My father’s father was gassed in 1916, but survived. Perhaps Dad had him in mind when he recorded this poem in 1942. Here’s his first page:

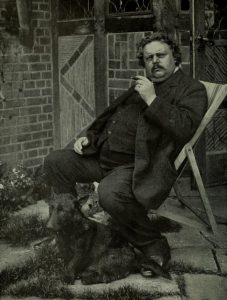

Reverend Geoffrey Studdert Kennedy was a volunteer British chaplain to the army on the western front, and was also known as Woodbine Willie for the Woodbines he smoked and handed out to the wounded and dying. He was a great anti-war poet.

Here’s the whole poem written in 1917 in soldier-dialect :

Thy Will Be Done

A Sermon in a Hospital

by Rev. G. A. Studdert Kennedy, from Rough Rhymes of a Padre, 1918

I WERE puzzled about this prayin’ stunt,

And all as the parsons say,

For they kep’ on sayin’, and sayin’,

And yet it weren’t plain no way.

For they told us never to worry,

But simply to trust in the Lord,

“Ask and ye shall receive,” they said,

And it sounds orlright, but, Gawd!

It’s a mighty puzzling business,

For it don’t allus work that way,

Ye may ask like mad, and ye don’t receive.

As I found out t’other day.

I were sittin’ me down on my ‘unkers,

And ‘avin’ a pull at my pipe,

And larfin’ like fun at a blind old ‘Un,

What were ‘avin’ a try to snipe.

For ‘e couldn’t shoot for monkey nuts,

The blinkin’ blear-eyed ass,

So I sits, and I spits, and I ‘ums a tune;

And I never thought o’ the gas.

Then all of a suddint I jumps to my feet,

For I ‘eard the strombos sound,

And I pops up my ‘ead a bit over the bags

To ‘ave a good look all round.

And there I seed it, comin’ across,

Like a girt big yaller cloud,

Then I ‘olds my breath, i’ the fear o’ death,

Till I bust, then I prayed aloud.

I prayed to the Lord Almighty above,

For to shift that blinkin’ wind,

But it kep’ on blowin’ the same old way,

And the chap next me, ‘e grinned.

“It’s no use prayin’,” ‘e said, “let’s run,”

And we fairly took to our ‘eels,

But the gas ran faster nor we could run,

And, Gawd, you know ‘ow it feels

Like a thousand rats and a million chats,

All tearin’ away at your chest,

And your legs won’t run, and you’re fairly done,

And you’ve got to give up and rest.

Then the darkness comes, and ye knows no more

Till ye wakes in an ‘orspital bed.

And some never knows nothin’ more at all,

Like my pal Bill–‘e’s dead.

Now, ‘ow was it ‘E didn’t shift that wind,

When I axed in the name o’ the Lord?

With the ‘orror of death in every breath,

Still I prayed every breath I drawed.

That beat me clean, and I thought and I thought

Till I came near bustin’ my ‘ead.

It weren’t for me I were grieved, ye see,

It were my pal Bill–‘e’s dead.

For me, I’m a single man, but Bill

‘As kiddies at ‘ome and a wife.

And why ever the Lord didn’t shift that wind

I just couldn’t see for my life.

But I’ve just bin readin’ a story ‘ere,

Of the night afore Jesus died,

And of ‘ow ‘E prayed in Gethsemane,

‘Ow ‘E fell on ‘Is face and cried.

Cried to the Lord Almighty above

Till ‘E broke in a bloody sweat,

And ‘E were the Son of the Lord, ‘E were,

And ‘E prayed to ‘Im ‘ard; and yet,

And yet ‘E ‘ad to go through wiv it, boys,

Just same as pore Bill what died.

‘E prayed to the Lord, and ‘E sweated blood,

And yet ‘E were crucified.

But ‘Is prayer were answered, I sees it now,

For though ‘E were sorely tried,

Still ‘E went wiv ‘Is trust in the Lord unbroke,

And ‘Is soul it were satisfied.

For ‘E felt ‘E were doin’ God’s Will, ye see,

What ‘E came on the earth to do,

And the answer what came to the prayers ‘E prayed

Were ‘Is power to see it through;

To see it through to the bitter end,

And to die like a Gawd at the last,

In a glory of light that were dawning bright

Wi’ the sorrow of death all past.

And the Christ who was ‘ung on the Cross is Gawd,

True Gawd for me and you,

For the only Gawd that a true man trusts

Is the Gawd what sees it through.

And Bill, ‘e were doin’ ‘is duty, boys,

What ‘e came on the earth to do,

And the answer what came to the prayers I prayed

Were ‘is power to see it through;

To see it through to the very end,

And to die as my old pal died,

Wi’ a thought for ‘is pal and a prayer for ‘is gal,

And ‘is brave ‘eart satisfied.

*

![Winter Tales by [de Vogüé, Eugène-Melchior]](https://images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/51TY38aUGhL.jpg)

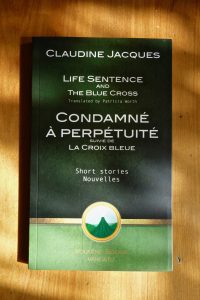

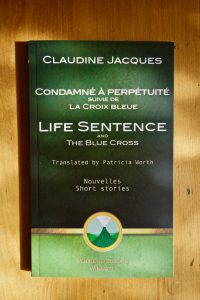

Life Sentence was published last year in Southerly Journal (Sydney University), and now it’s available in this little edition from Volkeno Books, Vanuatu. This is the second bilingual book published by Volkeno that includes Jacques’ original and my translation. The first was

Life Sentence was published last year in Southerly Journal (Sydney University), and now it’s available in this little edition from Volkeno Books, Vanuatu. This is the second bilingual book published by Volkeno that includes Jacques’ original and my translation. The first was