Never would I have translated Jean Lorrain if I knew then what I know now.

But that’s the beauty of reading a good book. The reader’s relationship is with the book and the story it tells, not its author.

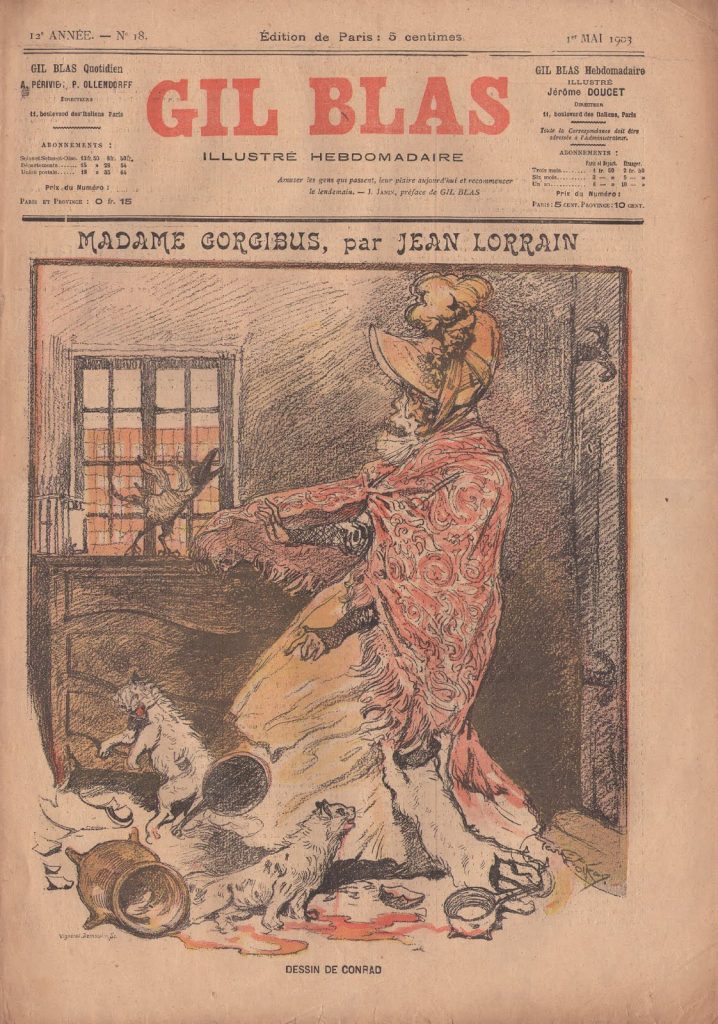

There’s much I could write about Jean Lorrain that would turn you away from all his work. But as a translator, I choose the writing, not the writer. After I’d read his little collection, Contes pour lire à la chandelle (Stories to Read by Candlelight), certain pieces stayed with me and compelled me to read them again. Before I knew a thing about Lorrain, I was touched by the sympathy he expressed for some of the underdogs of his society, like the odd old woman in ‘Madame Gorgibus’ and the trapped beauty in ‘Princess Mandosiane’.

There’s much I could write about Jean Lorrain that would turn you away from all his work. But as a translator, I choose the writing, not the writer. After I’d read his little collection, Contes pour lire à la chandelle (Stories to Read by Candlelight), certain pieces stayed with me and compelled me to read them again. Before I knew a thing about Lorrain, I was touched by the sympathy he expressed for some of the underdogs of his society, like the odd old woman in ‘Madame Gorgibus’ and the trapped beauty in ‘Princess Mandosiane’.

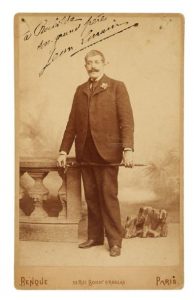

A brief bio: Jean Lorrain was born Paul Duval in 1855 and died of decadence in 1906 at the age of 51. He was the only child of a family of wealthy ship-owners. In 1882 he decided to become a writer, disappointing his father who suggested he take on an alias to avoid bringing shame on the family, thus Jean Lorrain was invented. He was a much-published journalist, poet, novelist, and sharp-tongued critic of his decadent peers, despite belonging to their circle.

While his work was well-known in his lifetime, much of it has been forgotten and will probably remain forgotten. But the stories I’ve selected to translate are worth resurrecting for their exquisite prose, particularly some that are in a category entitled ‘Tales for Sick Children’, that are quirky but not decadent like his novels. Their expression is nostalgic and aesthetic, typical of Belle Époque symbolists who rebelled against modern technology and yearned for a return of medieval days and characters in flamboyant gowns and armour.

His tales of knights and princesses, ghostly girls and frightful animated crockery are as masterfully worded as our favourite mythical adventures. What really clinched it for me were the illustrations accompanying several versions in issues of La Revue illustrée and Gil Blas, like the one above. Many of Lorrain’s stories were beautifully illustrated in the art nouveau of the era, not only in journals but also in deliciously decorated books. See this website for some excellent images from his books.

Here’s a taste of the writing that led me to translate it. To set the scene: Princess Mandosiane is embroidered onto a banner once used in grand processions and now stored in the crypt of a cathedral. A mouse tempts her with freedom:

Now, she lent her ear to the counsel of the red mouse, an insidious little mouse, fast as lightning, persistent and wilful, who had haunted her for years.

“Why stubbornly remain a captive, armour‑plated in all these pearls and embroidery holding you so tightly? Yours is not a life, you have never lived, not even during the times when you sparkled on those fine days of proclamations and pealing bells, cheered on by euphoric crowds, and now, you see, your life is oblivion, it is death. If you like, with my sharp teeth I could undo one by one the stitches of silk and gold cord that have held you in place for six hundred years, motionless in this lustrous velvet which, just between us, has lost its brilliance. It will perhaps hurt a little, especially when I unpick the stitches close to your heart, but I’ll begin with the long contours, those of your hands and your face, and already you will be able to stretch and move, and you will see how good it is to breathe and to live!’

Several of my translations of his stories have been published in journals in recent years, but soon the whole collection, “Stories to Read by Candlelight”, will be available. It’s presently being prepared for publication by Odyssey Books, a small Australian publisher.

*