Time-filling. And people watching. That’s what this is.

In Bluey’s café none of us has red hair.

Here’s to Mondays.

*

A quiet place.

From time to time a fairy ring grows beneath my Spruce fir tree. At the moment it’s not a whole circle but more of a semi-circular meandering of mushrooms across the lawn. It’s been growing for about a week and must be following a long root of this tall tree.

On Sunday I noticed one particular mushroom coming up in the nearby garden about five metres from the beginning of the line. It’s like a pop-up house for little people, and evokes Faerie, that land of enchantments and enchanted beings.

It’s expanding as it ages, yet the leaf-litter roof is still in place.

The small shelter over the mushroom makes it easy to understand why children could believe there are tiny fairy-folk residing within.

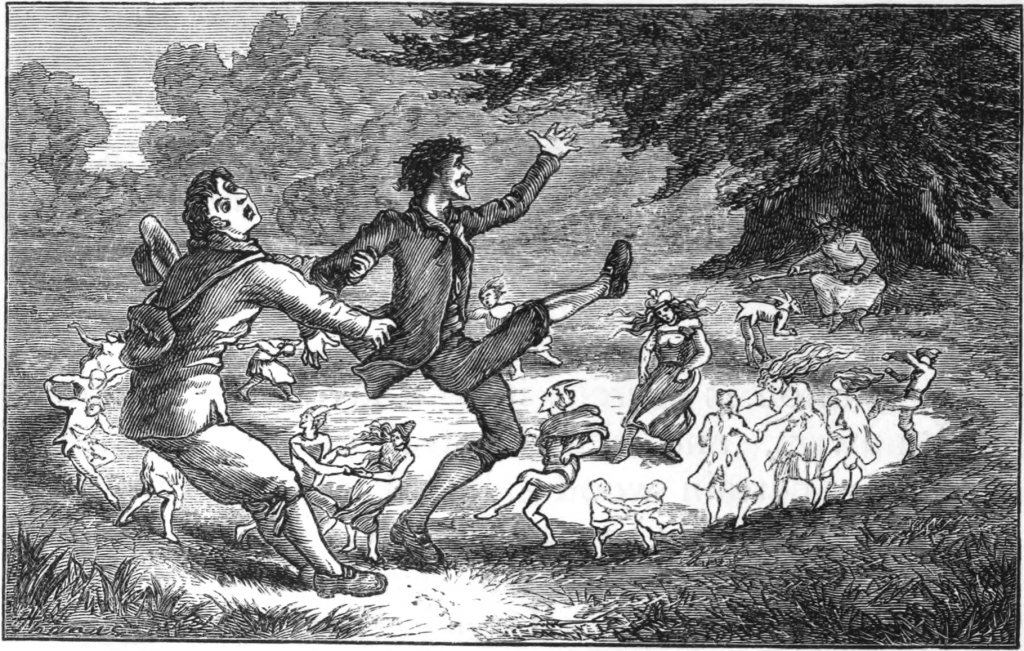

But recently I learnt that not only children have believed in fairies! Writers of Faerie in the 19th century (about 90% of whom were men) expressed a fearful respect for the little winged women, often passing a mention in their tales that fairy love was fatal to men. Male authors were wary of a fairy for she could transform or disguise herself. Small as she was, she could be mistaken for an insect or a bird, she could even become invisible, and, most dangerously, she could turn herself into a real woman. But the rule was that no man could love her and live.

I’ve read a lot of French fairy tales and have found it to be true. In Théodore de Banville’s story “La Chiffonnière”, for example, a fairy becomes an old ragpicker who is almost trampled by horses, but a kind-hearted poet picks her up where she falls, and in his arms she is rejuvenated, now young and beautiful. Though she wants to give him her love as a reward for saving her life, she knows it would kill him. Instead she offers him the finest cigar in the world, and four wishes.

Fairy rings are also things to beware of, to tread carefully around and not through. Men who entered the ring often disappeared and those who were tempted needed to be rescued. It seems the ancient curse has exhausted its power, for I’ve often stepped into mushroom rings in my lawn but have never disappeared…

While I know these fairies are not really magical, I also know that, in my garden, suddenly emerging fungi certainly are.

*

This is my last post for the year.

It’s a hot Christmas week here in Canberra, and to defeat the heat we’ve been for a couple of walks where trees are green and water is present if not plentiful.

Late in the afternoon we went to Dickson Wetlands where the water level was way down and was even a wee bit stagnant in places, but was as still as a millpond and good for reflecting (lol) on Christmas and the year that’s coming to a close.

As I flitted here and there photographing whatever turned my head, my husband sat on a rock and read War and Peace on his phone. He’s 22% of the way through it after several weeks, but clearly it’s more compelling than the wetlands.

Then this morning we went to the Botanic Gardens to walk in its cool rainforest (a great creation in a city where it doesn’t often rain). Water dragons were basking on the bitumen at the top of the stairs leading down into the tropical zone. They’re patient lizards, happy to be photographed.

As I turned to descend the stairs I hesitated. This was all I could see:

The mist was thick and white as a cloud, thanks to the misting system that makes a normally dry forest wet. I feared going forward, though my husband promised me I wouldn’t fall. How cool it was! Many degrees lower than up on the road. The lizard didn’t know what he was missing.

The stuff of fantasies was everywhere on the forest floor. I passed this moss-covered fern-tree stump just as the sun broke through the canopy and lit it up.

But all is not fairy tale magic in the forest. Just when we were really enjoying ourselves we came across the snake warning and turned back – a snake can spoil a good walk. Brown snakes, one of the reptiles commonly seen in these Gardens, apparently eat the water dragons. And the dragons eat the frogs. That’s why there’s no photo of a frog.

But water dragons can elude snakes and that’s why I found this lovely lizard waiting for us when we ascended the stairs.

***

When I began blogging seven years ago, I loved showing WW2 photos from my father’s collection, many of them unique, surprising, moving, even amusing. I’ve just stumbled on a few that I think I blogged about and then deleted for some obscure reason that I no longer remember. Here’s one that suits my mood today with its large pond of water set in a peaceful Cairo public garden where palm fronds frame a white swan and a black duck swimming peacefully, ignorant of the war.

Happy New Year to all my readers. In 2019, may you stay cool when it’s hot and warm when it’s not.

***

On Wednesday the weather put a dampener on my holiday, bringing ceaseless heavy rain that made it impossible for me to see a particularly interesting sight, the SeaCliff Bridge in Wollongong.

On Thursday the rain eased enough for me to try again. But shortly after walking onto the bridge and taking a photo or two, the rain came down again and I scampered.

Today is Friday and the sun is shining. Now I’m in Sydney, still in search of sights I’ve never seen. My host recommended I go to Palm Beach Bible Garden for a magnificent view of the land and sea, and an exploration of a unique garden. The garden and its view were generously donated to the public in 2006 by the trustees of Gerald Hercules Robinson who established it back in 1966.

Everyone else in this street has a similar view of Palm Beach and the isthmus joining it to Barrenjoey Headland, but they (probably) purchased theirs for multiples of millions of dollars. This is a place of affluence. Thanks to Mr Robinson, we the ordinary public can enjoy it for free, and in peace.

The concept of this garden is to grow only plants mentioned in the Bible. Every plant is accompanied by a small sign with its botanical name, common name, and the Bible reference where it can be found. The garden is a lovely place that’s carefully tended by volunteers, and indeed there was a woman pruning shrubs when we visited. It’s managed by the Pittwater Council in Sydney and can be booked for special events.

Here’s a sample of the many plants that grow surprisingly well here in Sydney, far from their ancient origins:

Hint for viewing my blog photos: I don’t understand why, but a better view of any of my photos can be obtained if you click once on any of them, then click again, then click yet again. You’ll end up with a full screen view in greater detail.

Seeing this garden was the highlight of my day. Tomorrow I’m marching further north, ever in pursuit of eye feasts.

*

Have you ever gone to a place for the first time because you read about it in a story?

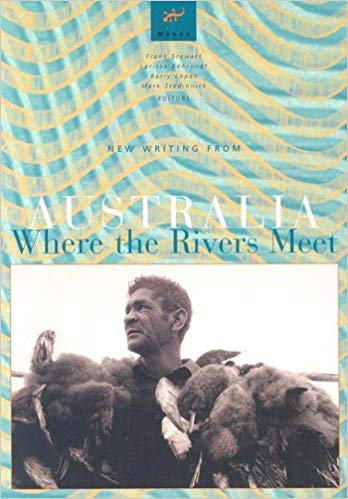

I recently read ‘On the Edge’ by an Australian writer, Ashley Hay. I came at it the long way round, beginning with ‘The Little Red Writing Book’ by Mark Tredinnick, a beautifully written, exceedingly helpful Australian book for writers who write like public servants but want to break away from that stilted language. Early in the book Tredinnick praises the writing of Barry Lopez, an American, and recommends Lopez’s writing about nature. So I went searching and saw Lopez’s name come up as an editor of ‘Where the Rivers Meet’, an Australian collection of short stories about our land, the nature of it, the history of it. ‘On the Edge’ was in it.

Ashley Hay wrote about the city of Wollongong, south of Sydney, built between the coastal mountains and the ocean and necessarily spreading north and south but never east or west. The whole city is ‘on the edge’ of Australia. She remembered being taken for a drive, as a teenager, along the road that once precariously hugged the steep cliffs prone to rockfalls, and compared it with the bridge that has replaced that road, the SeaCliff Bridge, a cantilevered serpentine bridge that follows the same coastline but in an open space over the ocean.

I tried to imagine it. I looked at the photos online, but I wanted to feel it, to see it.

Today, I’m in Wollongong, and am being driven to the bridge. It’s pouring, a deluge of rain that began at 5am and hasn’t stopped since. We’re on the bridge, three tourists in brightly coloured raincoats are taking photos of each other joyously holding their arms out as the rain beats down. Not another soul can be seen, and barely another car. I’m not as bold as the tourists, I can’t get out and walk in this weather, so we continue along the road up to Bald Hill Lookout where the cloud is low and the wind is gusting and whoomping the car. The view is supposed to look as it does in this advertisement for the new seats by Outdoor Design :

But today the view looks like this:

The sea is invisible, can’t open the windows, no point staying. We turn back towards the bridge and search for a place to stop so I can get out, stand still, and take in the view of this bridge I have only known in a story. The car parks are some distance away but I want to see what it’s like to walk on the bridge. I’ll need to take a photo and won’t be able to hold my umbrella steady in this wind, let alone a camera. It’s too hard, I give up and take a happy snap through the windscreen of our moving car.

The view was so blurred by the torrents of rain that if I hadn’t seen photos of the SeaCliff Bridge I still wouldn’t know what it looked like. So what have I gained by wanting to get inside someone else’s story?

Perhaps tomorrow will not be a rainy day.

*

It’s because of the advent of digitised records – birth, death, marriage and war service records – and family tree web sites, particularly Ancestry, that I know now what I didn’t know a short time ago. I’d heard about my father’s time in Egypt as a WW2 soldier and I’d heard about his own father’s time in France as a WW1 soldier.

But I’d never heard of the family members who were killed in action.

My grandmother had two cousins, the Burley brothers, James and Frederick, who were killed in Northern France.

Can you imagine losing two sons who voluntarily went to war?

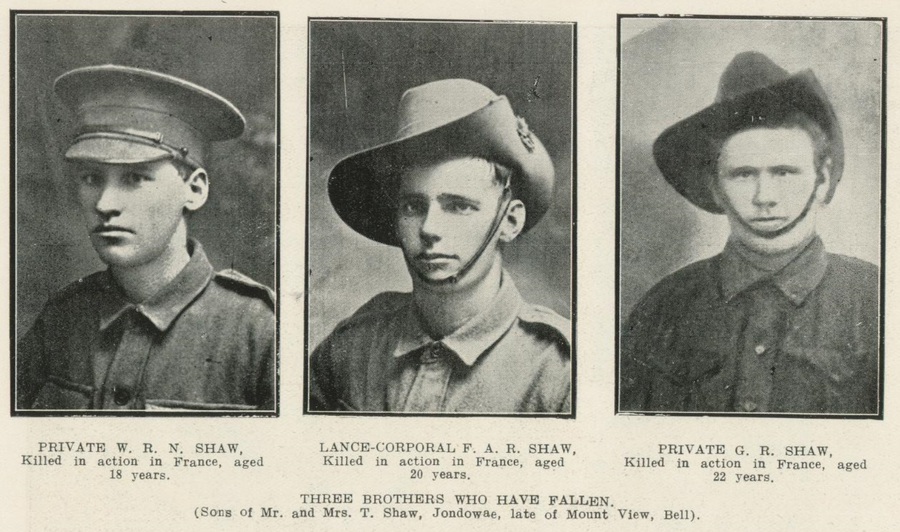

Now imagine losing three sons.

My grandfather had three cousins, the Shaw brothers, George, D’arcey and Frank, who were also killed in Northern France.

But because their cousin, my grandfather Ernest Bruce, survived gassing and a concrete wall falling on top of him, he returned to Australia to produce my father, who in turn produced me.

I’ve discovered most of this information through online records and family history websites. Many many family historians are using these resources now. This means that the great numbers of people commemorating the centenary of the armistice today, 11th November 2018, have learnt, like me, that they are the descendants of the ones who returned.

I have three sons. I feel absolute anguish for the parents who lost two or three of their children in war.

And I now have a greater appreciation of the struggles of Australians trying to build our nation a hundred years ago when the total population was 5 million, and 62,000 of their young people had been killed, and 156,000 were wounded, and many like my grandfather were unable to work again.

This building in the photo below, the Australian War Memorial, is ten minutes from my home. I’ve visited it countless times, and in the past few weeks as the crocheted and knitted poppies were displayed, and as I’ve read and heard so many stories from descendants of soldiers like me, I realise how fortunate I am that I have a comfortable home, enough food to keep me healthy, and a family that is gainfully employed. And I realise that WW1 was not the war to end all wars, there have been many wars since then, and I must not take my fortune for granted.

This new knowledge is greatly due to the digitisation of historical records, a technology I’m very grateful for.

*

The 11th of the 11th is not far off. The Australian War Memorial here in Canberra is demonstrating the community’s sorrow over all those who died in World War 1, the war to end all wars. Not. Crocheted and knitted poppies have been planted in the lawn, 62,000 of them, one for each of the dead, forming a sea of red spilling out in front of our beautiful war memorial building.

Poppy posts and photos are appearing all around the country. I’ve read that 62,000 poppies was the goal for the project, but the women (mostly women) contributed many many more. The extras have been used in a display in Parliament House and in towns around Australia. I made 12, and I taught my Japanese student to crochet and then she made 12. Our 24 poppies are there in the crowd somewhere.

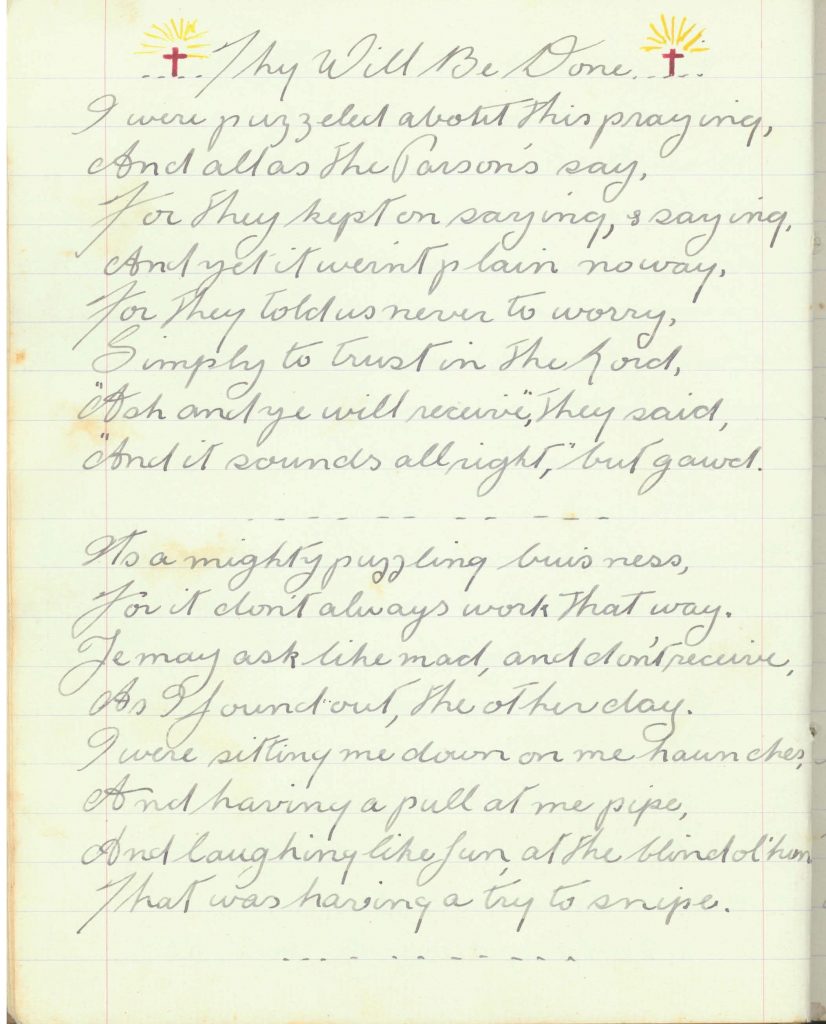

All this talk about the centenary of the armistice reminded me of a poem I read in my father’s poetry book that he brought back from World War 2. He recorded poems he wanted to remember, and re-reading this one leaves me wondering what it meant to him, especially the final verse. The poet was Rev. G. A. Studdert Kennedy who allowed it to be circulated among the soldiers. It speaks of a death by gassing and may have comforted some of those who had lost mates to this horrific weapon. My father’s father was gassed in 1916, but survived. Perhaps Dad had him in mind when he recorded this poem in 1942. Here’s his first page:

Reverend Geoffrey Studdert Kennedy was a volunteer British chaplain to the army on the western front, and was also known as Woodbine Willie for the Woodbines he smoked and handed out to the wounded and dying. He was a great anti-war poet.

Here’s the whole poem written in 1917 in soldier-dialect :

Thy Will Be Done

A Sermon in a Hospital

by Rev. G. A. Studdert Kennedy, from Rough Rhymes of a Padre, 1918

I WERE puzzled about this prayin’ stunt,

And all as the parsons say,

For they kep’ on sayin’, and sayin’,

And yet it weren’t plain no way.

For they told us never to worry,

But simply to trust in the Lord,

“Ask and ye shall receive,” they said,

And it sounds orlright, but, Gawd!

It’s a mighty puzzling business,

For it don’t allus work that way,

Ye may ask like mad, and ye don’t receive.

As I found out t’other day.

I were sittin’ me down on my ‘unkers,

And ‘avin’ a pull at my pipe,

And larfin’ like fun at a blind old ‘Un,

What were ‘avin’ a try to snipe.

For ‘e couldn’t shoot for monkey nuts,

The blinkin’ blear-eyed ass,

So I sits, and I spits, and I ‘ums a tune;

And I never thought o’ the gas.

Then all of a suddint I jumps to my feet,

For I ‘eard the strombos sound,

And I pops up my ‘ead a bit over the bags

To ‘ave a good look all round.

And there I seed it, comin’ across,

Like a girt big yaller cloud,

Then I ‘olds my breath, i’ the fear o’ death,

Till I bust, then I prayed aloud.

I prayed to the Lord Almighty above,

For to shift that blinkin’ wind,

But it kep’ on blowin’ the same old way,

And the chap next me, ‘e grinned.

“It’s no use prayin’,” ‘e said, “let’s run,”

And we fairly took to our ‘eels,

But the gas ran faster nor we could run,

And, Gawd, you know ‘ow it feels

Like a thousand rats and a million chats,

All tearin’ away at your chest,

And your legs won’t run, and you’re fairly done,

And you’ve got to give up and rest.

Then the darkness comes, and ye knows no more

Till ye wakes in an ‘orspital bed.

And some never knows nothin’ more at all,

Like my pal Bill–‘e’s dead.

Now, ‘ow was it ‘E didn’t shift that wind,

When I axed in the name o’ the Lord?

With the ‘orror of death in every breath,

Still I prayed every breath I drawed.

That beat me clean, and I thought and I thought

Till I came near bustin’ my ‘ead.

It weren’t for me I were grieved, ye see,

It were my pal Bill–‘e’s dead.

For me, I’m a single man, but Bill

‘As kiddies at ‘ome and a wife.

And why ever the Lord didn’t shift that wind

I just couldn’t see for my life.

But I’ve just bin readin’ a story ‘ere,

Of the night afore Jesus died,

And of ‘ow ‘E prayed in Gethsemane,

‘Ow ‘E fell on ‘Is face and cried.

Cried to the Lord Almighty above

Till ‘E broke in a bloody sweat,

And ‘E were the Son of the Lord, ‘E were,

And ‘E prayed to ‘Im ‘ard; and yet,

And yet ‘E ‘ad to go through wiv it, boys,

Just same as pore Bill what died.

‘E prayed to the Lord, and ‘E sweated blood,

And yet ‘E were crucified.

But ‘Is prayer were answered, I sees it now,

For though ‘E were sorely tried,

Still ‘E went wiv ‘Is trust in the Lord unbroke,

And ‘Is soul it were satisfied.

For ‘E felt ‘E were doin’ God’s Will, ye see,

What ‘E came on the earth to do,

And the answer what came to the prayers ‘E prayed

Were ‘Is power to see it through;

To see it through to the bitter end,

And to die like a Gawd at the last,

In a glory of light that were dawning bright

Wi’ the sorrow of death all past.

And the Christ who was ‘ung on the Cross is Gawd,

True Gawd for me and you,

For the only Gawd that a true man trusts

Is the Gawd what sees it through.

And Bill, ‘e were doin’ ‘is duty, boys,

What ‘e came on the earth to do,

And the answer what came to the prayers I prayed

Were ‘is power to see it through;

To see it through to the very end,

And to die as my old pal died,

Wi’ a thought for ‘is pal and a prayer for ‘is gal,

And ‘is brave ‘eart satisfied.

*

Just as there are brand new leaves appearing on bare branches, and even tiny fruit emerging on my fig and plum trees, new little beings have come into the animal kingdom now that spring has sprung. I’ve seen a number of baby animals in past weeks, little beauties who stay close to their parents, reminding me how intimate a relationship it is. Seeing a brand new duck or cow is such a feel-good moment. Or a possum joey’s claws poking out of its mother’s pouch. Or a tiny kangaroo joey’s head on its mother’s belly.

And high up in trees or in other secret nesting places, countless birds have been breeding. I don’t have photos but I’ve seen the chicks and their parents every day since September when there was a sudden explosion in the bird population in my garden. There are all sorts here in Canberra that I never knew existed when I lived in Brisbane, from Gang-gang Cockatoos to tiny Eastern Spinebills, often right outside my window, in the same hakea tree where I saw the mother possum and her joey. This hakea grew naturally amid some introduced species like maples and ash and white may, and I didn’t even notice it until it was taller than its competitors. Now I have all these animal visitors because of this tree.

It’s a blessing to be presented with new life in the animal world, and even more of a blessing that they pose for me while I take their photo, for they all patiently sat and waited while I got my photography act together!

*

Apparently, it’s good for writers to write reviews of other writers’ work. I’ve never done it and never wanted to, till now.

I had a great morning walking round some natural ponds and listening to hundreds of frogs croaking among reeds, all thanks to one small book: Walking Canberra by Graeme Barrow, self-published in 2014. So I feel compelled to share this pleasure with anyone who might be contemplating a walk in our beautiful bush capital. Here goes my first book review…

Waiting to be served at my local newsagent, my eyes fell on this little book propped up among the sweets at the counter. The full title held my attention: Walking Canberra: 101 ways to see Australia’s national capital on foot. I’d long been considering how to get some exercise and at the same time discover some of the unknown treasures and pleasures in our world, and this title promised to deliver exactly that.

Walking Canberra is nothing like the stuff I work on as a translator, it’s neither a fairy tale nor a New Caledonian drama, yet it’s currently a favourite book that I’ve been referring to for the past four weeks. I’ve heard there aren’t many copies left because it’s going out of print. Graeme Barrow self-published his books through his own business, Dagraja Press. He was a Canberra journalist who wrote books on bushwalking in this region, as well as a few local histories. He died in May last year, so here’s hoping that someone else will take on the project of updating his advice on walking in Canberra’s parks and bushland as the city changes and grows and old paths and landmarks are moved or removed.

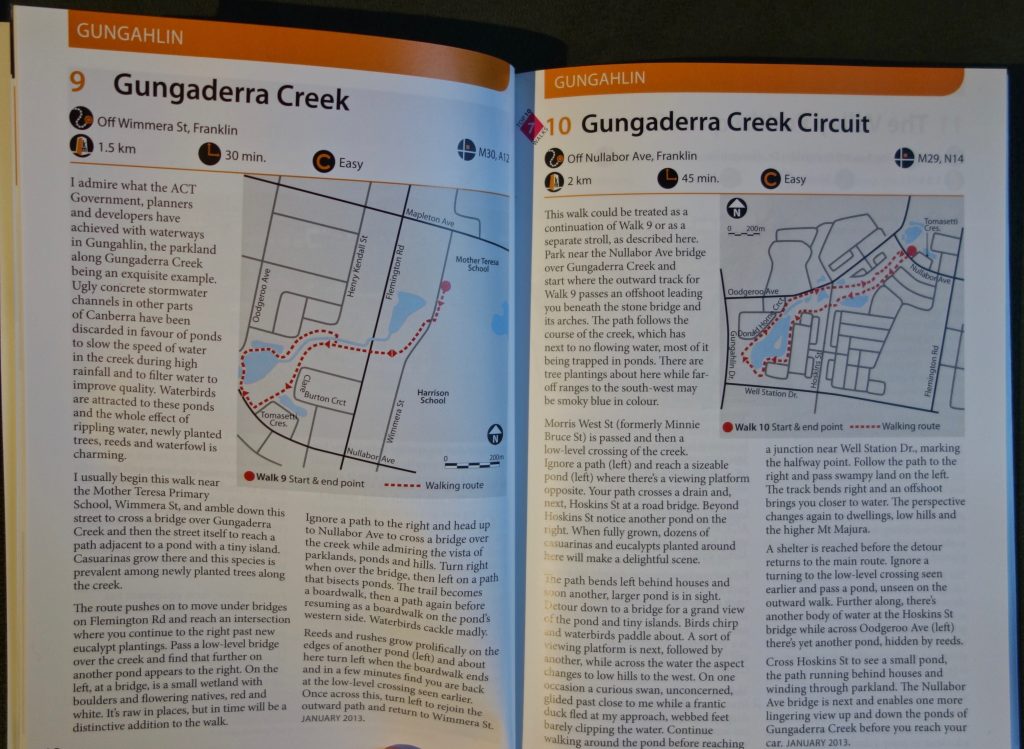

Barrow wrote like a friend to friends. The information and instructions are clear as a bell, and though he published it in 2014, I’ve found that the details (in the walks I’ve taken so far) are still correct. There are small maps on each page, and a description of what to see along the way, an outline of where to turn, where to linger and what to avoid.

Last weekend and this, my husband and I walked the Gungaderra Creek Circuit, chosen by me because of its level of difficulty: “Easy”. The local government has created a series of ponds instead of the usual concrete stormwater drains, and these ponds attract water birds and frogs frogs frogs which are invisible among the reeds but loud! There are no frogs in my suburb so this sound was a surprise.

While walking in what is essentially still suburbia, there are reminders here and there of human slips in the design: a thorny rosebush growing as though grafted onto a young eucalypt, a pink soccer ball fallen into the dense reed bed…

… and there’s the street beside Gungaderra Creek that was named and renamed after two Australian authors…

Minnie Bruce was the author Mary Grant Bruce, famous for her Billabong series, who was granted a street name in a suburb (Franklin) where Australian authors were the theme. Ten years ago her family asked for the name to be revoked since her mother was known as Minnie, and Mary was known as Mary (despite being named Minnie at birth). So, Morris West, another Australian author, was given the street. West was famous for many novels but particularly his first, The Devil’s Advocate, which has been reprinted more times than any other modern Australian novel. Now there’s a claim to fame that deserves its own street!

Out of the 101 ways to see Australia’s national capital on foot I’ve already done about 47 by dint of having lived here for 21 years. I’m thrilled to have found this special book that gives me ideas for filling my free days for the next 21 years.

*

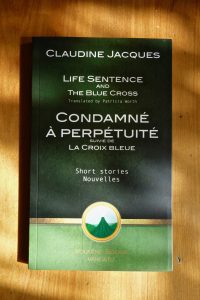

Today I was thrilled to receive ten copies of a small bilingual book of two short stories, Life Sentence and The Blue Cross, my translations of Condamné à perpétuité and La Croix bleue by the New Caledonian author, Claudine Jacques.

Life Sentence was published last year in Southerly Journal (Sydney University), and now it’s available in this little edition from Volkeno Books, Vanuatu. This is the second bilingual book published by Volkeno that includes Jacques’ original and my translation. The first was Le Masque / The Mask. Both The Mask and the new book are available to purchase from Les Éditions noir au blanc.

Life Sentence was published last year in Southerly Journal (Sydney University), and now it’s available in this little edition from Volkeno Books, Vanuatu. This is the second bilingual book published by Volkeno that includes Jacques’ original and my translation. The first was Le Masque / The Mask. Both The Mask and the new book are available to purchase from Les Éditions noir au blanc.

Life Sentence is concerned with leprosy, once an incurable disease among poorer New Caledonians. The Blue Cross tells the story of a wife dealing with an alcoholic husband. Both stories end with hope.

*