I haven’t left town this month, but I have visited the National Museum which gave me plenty of opportunities to snap photos. Ours is a museum of social history. Neither the content nor the architecture is traditional, which is obvious even before arriving at the car park: the introduction to the building is this giant 30m high loop, part of what is called the Uluru line:  In the foyer there are great glass windows looking onto the lake, and an artsy window dressing which produces the best shadows.

In the foyer there are great glass windows looking onto the lake, and an artsy window dressing which produces the best shadows.  As I moved up into the galleries, Eternity caught my eye. Arthur Stace famously wrote this single word in beautiful copperplate writing on the footpaths of Sydney between 1932 and 1967.

As I moved up into the galleries, Eternity caught my eye. Arthur Stace famously wrote this single word in beautiful copperplate writing on the footpaths of Sydney between 1932 and 1967.  Stace described an experience in church which prompted him to write Eternity half a million times over 35 years:

Stace described an experience in church which prompted him to write Eternity half a million times over 35 years:

John Ridley was a powerful preacher and he shouted, ‘I wish I could shout Eternity through the streets of Sydney.’ He repeated himself and kept shouting, ‘Eternity, Eternity’, and his words were ringing through my brain as I left the church. Suddenly I began crying and I felt a powerful call from the Lord to write ‘Eternity’. I had a piece of chalk in my pocket, and I bent down right there and wrote it. I’ve been writing it at least 50 times a day ever since, and that’s 30 years ago … I think Eternity gets the message across, makes people stop and think. (courtesy National Museum of Australia website)

From reflecting on eternity I was taken back in time to the largest of all marsupials, the extinct Diprotodon. After all, it wouldn’t be a museum without a skeleton. Here’s the Diprotodon in and out of its skin:

An unmissable object in the Museum is an old windmill, its sails turning slowly and windlessly, old technology driven by new. It’s a Simplex windmill from Kenya station, north-east of Longreach in central Queensland. The windmill provided water for stock from a shallow bore, from the 1920s until 1989, when a deeper artesian bore came into service. It was one of two windmills on 25,000 acres! As the windmill owner, John Seccombe, who donated it to the museum says, Australia couldn’t have survived without windmills.  One of the saddest sights in the museum was this gate, a reminder of times when some children were raised by institutions:

One of the saddest sights in the museum was this gate, a reminder of times when some children were raised by institutions:  There were other objects like leg irons and old pistols that remind us of our darker colonial past: and a convict bi-colour ‘magpie’ uniform, designed to deter convicts from escaping. But imagine the situation if, in 1788 and later, the roles had been reversed, and it wasn’t the English arriving to claim this land for the crown, but the Aboriginals arriving to take the land from the whites. Gordon Syron, an indigenous artist painted that ‘what if’ scene in The Black Bastards are Coming, 2006:

There were other objects like leg irons and old pistols that remind us of our darker colonial past: and a convict bi-colour ‘magpie’ uniform, designed to deter convicts from escaping. But imagine the situation if, in 1788 and later, the roles had been reversed, and it wasn’t the English arriving to claim this land for the crown, but the Aboriginals arriving to take the land from the whites. Gordon Syron, an indigenous artist painted that ‘what if’ scene in The Black Bastards are Coming, 2006:  Out on the museum terrace, one of the best spots to get a quiet waterside coffee, I was contemplating eternity when a man and dog came past on a surfboard (lakeboard?).

Out on the museum terrace, one of the best spots to get a quiet waterside coffee, I was contemplating eternity when a man and dog came past on a surfboard (lakeboard?).

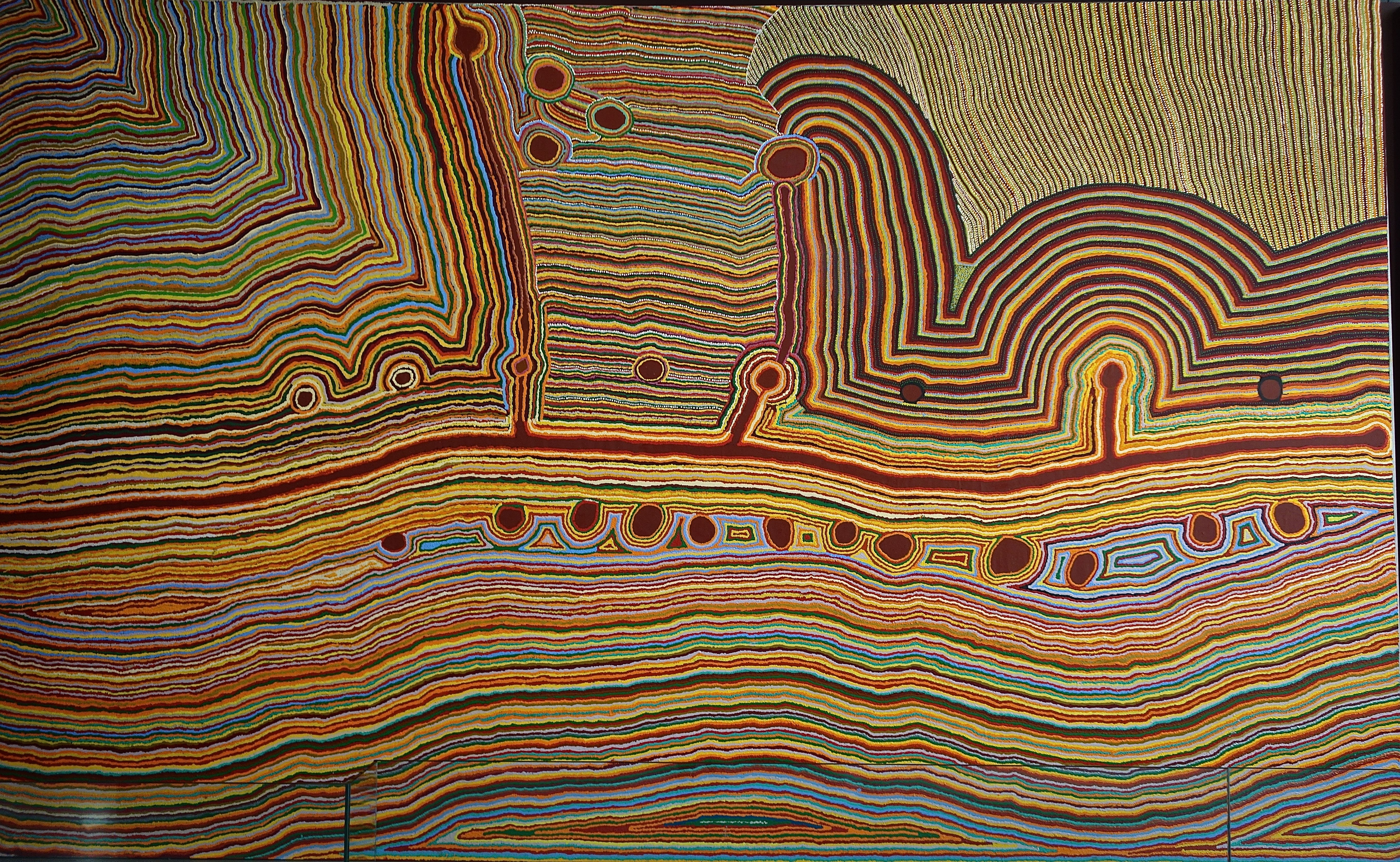

Before I go, if you’re wondering about the header image, it’s part of Martumili Ngurra, 2009, hanging in the museum foyer, painted in acrylic on linen by six Martu women from central Western Australia. Ngalangka Taylor, one of the artists, says:

“When you look at this painting, don’t read it like a whitefella map. It’s a Martu map: this is how we see the country.”

The painting shows tracks and roadways and geographical sites related to mining and pastoral activities introduced in the 19th century in their part of Australia.

More next month. Until then, see some other monthly trips on Marianne’s East of Málaga. She challenges us to take one trip EVERY month.

![The Collector | [John Fowles] The Collector | [John Fowles]](http://ecx.images-amazon.com/images/I/51V1elV05rL._SL300_.jpg)

![The Book of Ebenezer le Page | [G. B. Edwards] The Book of Ebenezer le Page | [G. B. Edwards]](http://ecx.images-amazon.com/images/I/51qkZldzsaL._SL300_.jpg)