I stumbled on a reading challenge by my local ACT library this week, and at first I dismissed it as I do with challenges generally. But the list of categories looked manageable for what remains of 2019 and the thought occurred to me that I could tick them off, no worries. It came to me a few days after I found a new library in the small Australian Catholic University around the corner from me that has a very welcoming wall at the entrance. Here it is. Zoom in (click and click again) to read students’ stick-it notes…

Here I picked up a book I’d always avoided for no good reason, The Magic Pudding by Norman Lindsay, an early Australian classic, which fits one of the categories of the challenge, ‘Something you regret not having read yet’.

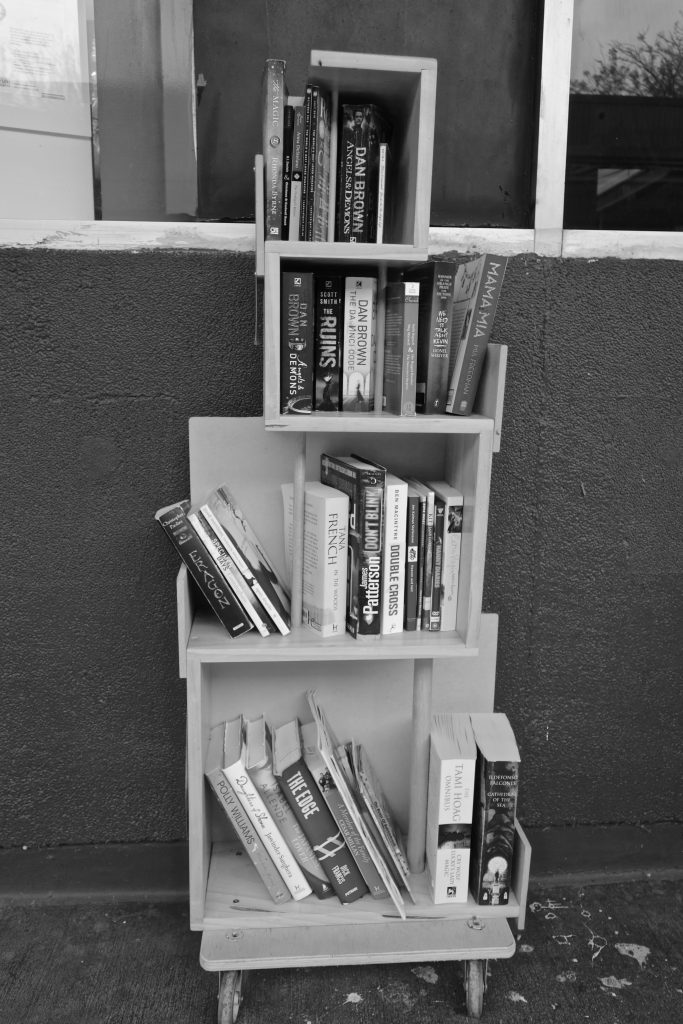

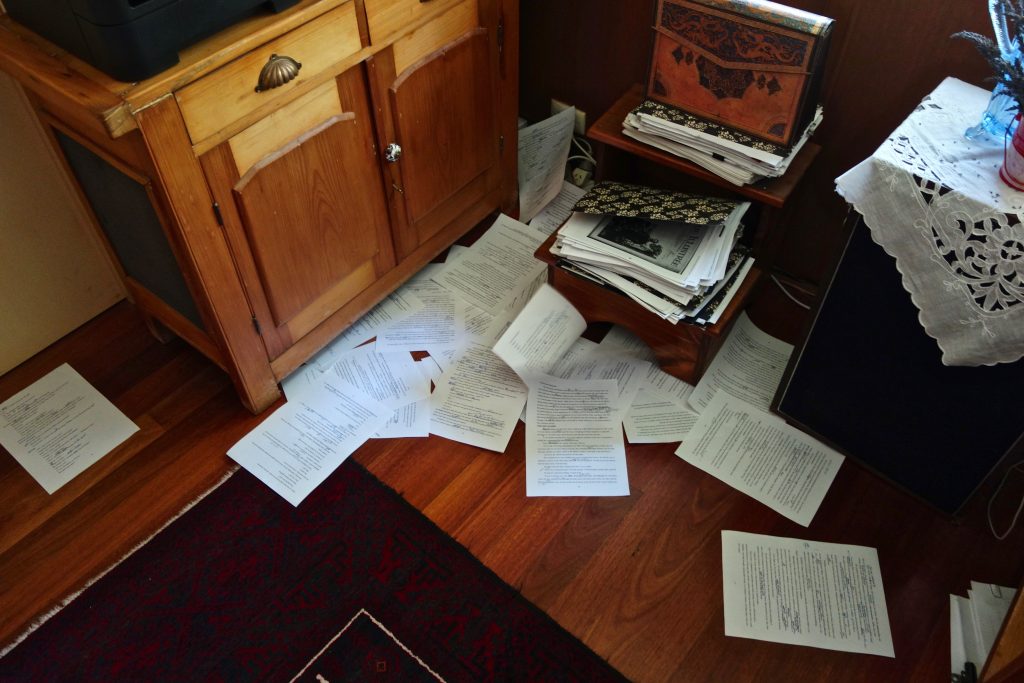

And then this morning, I cast my eye quickly over the pop-up library outside a local café. Zoom in to see what sort of books Canberrans read…

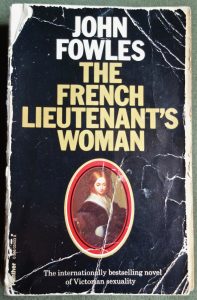

There on the shelf was a book that someone once highly recommended, The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini. I’ve brought it home, except now I remember having read it, but it fits another challenge category, ‘Something you want to re-read’.

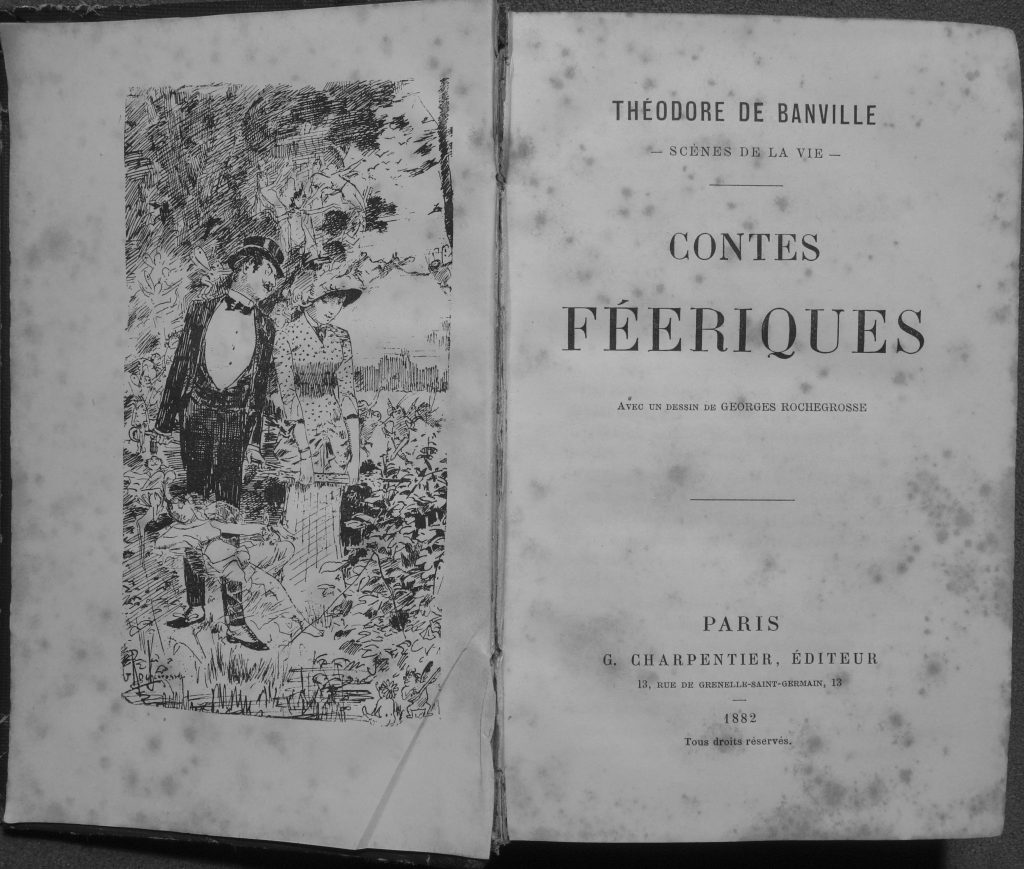

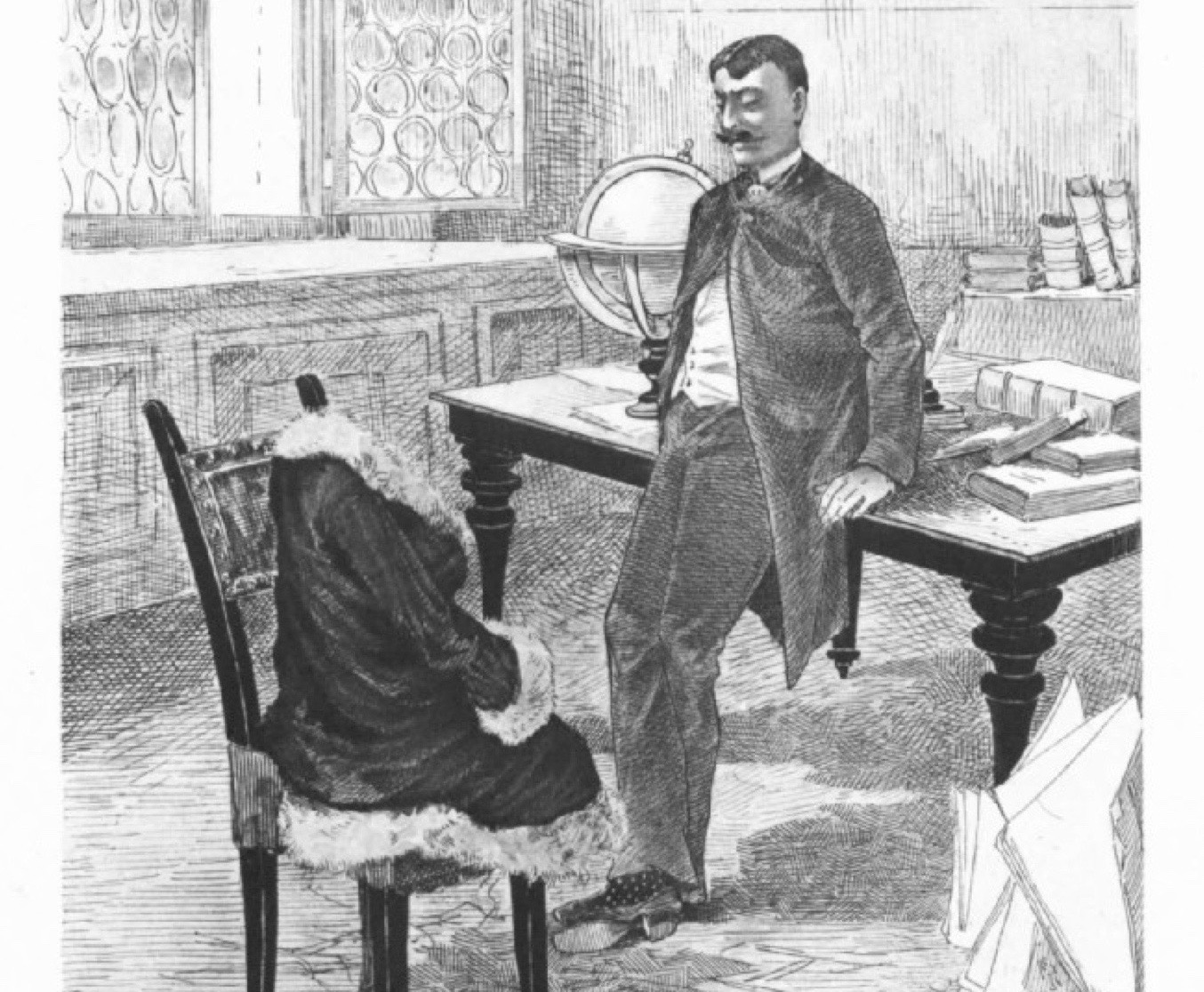

That’s two. But I have a third book that fits the category ‘Set in an imaginary world’: Contes féeriques (Faeric Tales) by Théodore de Banville. The title page is illustrated by Georges Rochegrosse, his stepson. Note the age spots, it’s an old one. Zoom in to see the fairies floating around the amorous couple…

Banville wittily gives it the subtitle ‘Scenes from Life’, but every tale revolves around the intervention of a fairy, magician or other supernatural figure! I recently had a translated story published that comes from this collection, ‘The Lydian’ which you can read for free if you click the link, and if you click here you can read more about it. But I haven’t yet read every story in the book, so it’s going on my challenge list.

That’s three, and only seventeen more to find to tick off everything on the challenge list. It should take my reading to the end of this year:

2019 Libraries ACT Reading Challenge

- A genre you’ve never read before

- Something that makes you laugh

- Has a one-word title

- Features time travel or time slip

- Written under a pseudonym

- That celebrates diversity

- Set in an imaginary or alternate world

- Crime fiction

- Features food

- Something you can read in a day

- Has a green cover

- An eBook or eAudiobook

- Set in Africa

- A gothic story

- Something you want to re-read

- Something you regret not having read yet

- Recommended by family or friend

- From/about antiquity (before Middle Ages)

- Epistolary (letter or diary format)

- Recommended by library staff

*